AMPLIFY VOL. 36, NO. 3

The business sector, in collaboration with various stakeholders, is instrumental in providing resources and solutions to address the biodiversity crisis. Biodiversity is declining at an alarming rate, and the costs of inaction — compromised organizational legitimacy and reputation, raw-material shortages, and intensified ecological crises — are increasing. The global community has called for immediate widespread action to “bend the curve” of biodiversity decline.1

There is increasing evidence of global biodiversity decline. This is alarming given that, according to the World Economic Forum, more than half of global GDP is highly or moderately dependent on ecosystem services, and businesses are more dependent on nature than was previously thought.2

Businesses control substantial resources and knowledge that can, and must, be harnessed for biodiversity action. Business’s response to biodiversity decline has the power to accelerate activities across our societies or, through inaction, hamper societal responses.

There is strong evidence of positive movement, including societal transitions and frameworks that enable harmony with nature. Businesses are now involved with numerous multi-stakeholder networks that aim to develop solutions to thorny sustainability issues, and nature positive language is becoming more commonplace in business.3 Focusing on what’s possible and amplifying positive steps are of utmost importance to implementing change on a short timescale.

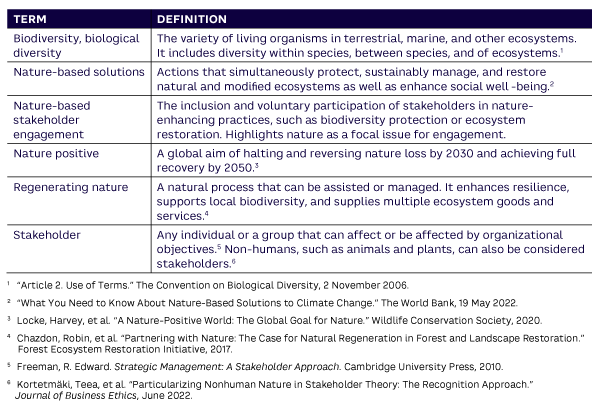

We suggest that new phrases are needed to catalyze biodiversity action. The term “nature-based stakeholder engagement” is discussed in this article as a potential candidate, as it connects two powerful notions. “Nature-based solutions” include actions that both protect natural ecosystems and enhance social well-being.4 “Stakeholder engagement” refers to the inclusion of stakeholders in organizational practices.5 Thus, nature-based stakeholder engagement highlights nature as a focal issue for engagement and the need to include a wide variety of stakeholders in nature-enhancing practices like biodiversity protection.

New Phrase Promotes Key Connections

Recent sustainability research shows that certain types of language, fresh vocabulary, and attractive metaphors are extremely helpful in initiating and boosting collaborative action for sustainability transformation.6 (Note that we’re using the term “metaphor” in the Aristotelian sense: a perception of the similarity in the dissimilar.)

It’s time to look closely at the role of language in creating vocabulary with sufficient weight and practical relevance to catalyze biodiversity action in business-stakeholder networks.

We believe the term “nature-based stakeholder engagement” has the potential to establish a connection between regenerating nature, nature-based solutions, and the business sector and to initiate biodiversity action in business-stakeholder networks.

We argue that this phrase is impactful and meaningful because it derives from terms that are part of different discourses: stakeholder engagement and nature-based solutions. Stakeholder engagement is an established construct in management and strategy, as well as in environmental management research and practice.7 The phrase “nature-based solutions” is widely used in environmental practice and policy making.8

Thus, the concept of nature-based stakeholder engagement transfers “nature” into the domain of business management and stakeholder collaboration and gains power through the interaction and the entangled association of two established discourses.9 This type of vocabulary has the potential to create a bridge between academic and practitioner communities.

Frameworks Guiding Biodiversity Action in Business

Debates about biodiversity decline have spurred a variety of frameworks guiding biodiversity action. The terms “regenerating nature” and “nature-based solutions” have recently gained traction in policy making.

The term “regenerating nature” has a high amount of international appeal. Regeneration refers to a natural process that can be assisted or managed and that facilitates ecosystem recovery. The term has become associated with current discussions on ecological restoration, biodiversity, and the circular economy.10,11 For example, the European Union (EU) has proposed the Nature Restoration Law, the first-ever legislation targeting ecosystems, habitats, and species restoration across the EU.12

Nature-based solutions is another practice with a biodiversity focus that has been successfully promoted by the EU.13 Nature-based solutions are actions to protect, sustainably manage, and restore natural and modified ecosystems. At the same time, they address societal challenges and enhance the well-being of people and nature.14

The increasing interest from business in discussing these ideas is promising.15 However, a practical connection to business vocabulary seems to be missing.

What Motivates Biodiversity Action?

Environmental and behavioral research has proven that although raising awareness is the first step in creating action, it is not sufficient to maintain momentum without routines and practices supporting the change.16 There are several drivers of business biodiversity action, and while every organization is driven by a unique combination, there are some commonalities.

First, corporate sustainability aims have become a standard organizational practice for many businesses. Biodiversity is increasingly acknowledged as a part of these goals.17 For example, cosmetics company L’Oréal has measurable biodiversity targets for 2030 that include diminishing impact on deforestation and creating a positive impact on biodiversity at all industrial sites.18

Second, biodiversity protection is driven by industry-wide practices and guidelines. Institutionalized practices, together with expectations and contributions from customers and other stakeholders, are creating a push for biodiversity action. Industry practices, such as establishing stakeholder networks, can also create a pull for biodiversity responses since stakeholder collaboration provides access to diverse knowledge bases and enhances organizational legitimacy in the face of complex problems.

Third, as human and business impacts on biodiversity loss raise ethical concerns, biodiversity protection has grown into an ethical imperative of public and private decision makers. Ethical reasons also include acknowledging the intrinsic value of nature and biodiversity beyond instrumental benefits, including conserving nature for future generations.

Fourth, policy frameworks seek to guide businesses‘ biodiversity activities. However, current frameworks and regulations have proven ineffective in addressing biodiversity loss. There is evidence of business responses, but it is not extensive or quick enough. Novel approaches are needed to catalyze immediate, widescale action.

Why Language Is Essential to Catalyzing Action

Language shapes how we understand and respond to environmental challenges. Narratives and stories are powerful in making issues and events meaningful and understandable, and metaphors affect our willingness to engage.

Stories and metaphors can be used to maintain the status quo or catalyze change. Performativity of language refers to language functioning as a form of social action. Oral and textual communication transmit knowledge of possible courses of action. Language used as social interaction both enables and limits what is possible and desirable — focus and targets of action, as well as outcomes, are defined in language use.19

Many of our current terms and metaphors have been proven ineffective in spurring large-scale biodiversity action. Novel approaches are needed to connect actors from various sectors and prompt action, and their vocabulary must resonate across business sectors, cultures, and social groups. A joint vocabulary is needed to make widespread biodiversity protection a reality.

Practice-based language can activate change. It builds on vocabulary that is already in use and proven effective, accentuating its value across various stakeholder groups. When stakeholders have joint interests and share concepts and language related to those interests, change is more likely to happen.

Nature-Based Stakeholder Engagement Catalyzing Biodiversity Action

When it comes to biodiversity issues, stakeholder engagement is touted as elemental by the private sector, government entities, and nonprofits. That engagement can follow a company-centric or issue-focused model.20 The more traditional company-centric model focuses on achieving the company’s goals. Issue-focused models center on a focal issue (e.g., biodiversity protection or nature positive value creation) and create a multi-stakeholder network to address the issue.

Nature-based stakeholder engagement combines the established vocabulary of stakeholder engagement with the term “nature-based,” denoting nature as a focal issue for the engagement. The term “nature-based” includes a variety of nature-enhancing activities, such as nature positive, biodiversity protection, and nature-based solutions.

We believe the term “nature-based stakeholder engagement” has both relevance to and resonance with established practices, allowing it to serve as a metaphor for catalyzing and concretizing biodiversity action in a business context.

Benefits of Nature-Based Stakeholder Engagement

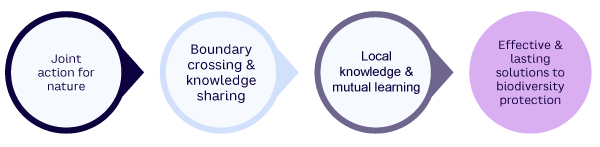

There are four key benefits to the concept of nature-based stakeholder engagement (see Figure 1). First, it directly connects with the idea of joining forces for nature. Partnerships and alliances are widely recognized as key to biodiversity action. Stakeholder collaboration is appealing to many types of organizations since the implications of biodiversity action transcend organizational boundaries.

Second, it enables boundary crossing and knowledge sharing. Most companies lack in-house expertise in biodiversity. When companies partner with nonprofits, they build biodiversity expertise; when nonprofits partner with businesses, they gain business skills. A good example is Shell’s partnership with the International Union for Conservation of Nature and UNESCO programs. Through secondments, the organizations increased staff empowerment, job satisfaction, meaningfulness, and expertise.21

Third, nature-based stakeholder engagement encourages reliance on local knowledge, an understanding of the challenges and their solutions in their local context, and the need for knowledge exchange among various stakeholders. The idea of mutual learning is at the very core of stakeholder engagement.22 Multi-stakeholder initiatives can support a variety of viewpoints and their integration, bringing together policy makers, businesses, scientists, local communities, and other stakeholders.23

Fourth, nature-based stakeholder engagement can lead to effective, lasting solutions to support biodiversity action. Effective solutions require expert knowledge that can be gained when businesses collaborate with nongovernmental organizations, public sector actors, research and academic institutions, and local communities. Certain actions, such as creating protected areas, require active multi-stakeholder collaboration. Various stakeholders have their own interests, but these can often coexist in a network. For example, businesses can focus on their strategic and commercial goals while public actors aim to enhance social welfare.

The idea of nature-based stakeholder engagement puts nature’s point of view at the forefront to encourage solution finding and complexity management.

Examples of Nature-Based Stakeholder Engagement

There are already some instances of businesses and organizations enacting biodiversity protection in stakeholder engagement. Energy company Neste collaborates with the wildlife conservation organization Fauna & Flora International in biodiversity conservation. Neste aims to have a positive impact on biodiversity throughout its value chain by 2040.24

Holcim, a multinational building materials company, says it aims to become a leading voice in protecting biodiverse landscapes through multi-stakeholder collaboration. Its target landscapes include forests, grasslands, deserts, and aquatic habitats. These landscapes provide numerous ecosystem services for people while supporting flora and fauna.25

Unilever, one of the world’s largest consumer goods companies, highlights the need for stakeholder engagement on biodiversity. It has pressed for an ambitious global agreement and action on nature to build a stable, net-zero, nature positive, equitable future for humanity and life on Earth. In addition to governmental action, Unilever calls for all businesses to take steps now to regenerate nature.26

The Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures is a good example of an industry-based private sector partnership. As a global, market-led network of 40 large financial institutions and corporations supported by scientific partners and governments, it aims to direct global financial flows toward nature positive outcomes.27

Conclusion

We have suggested the term “nature-based stakeholder engagement” as an example of new language that speaks to a wide variety of audiences. Our demonstration serves as an example for business leaders who want to make a difference in action-oriented biodiversity conservation by generating language with the potential to be widely adopted by businesses, institutions, and the conservation community.

The concept of nature-based stakeholder engagement engenders a better understanding of the term “biodiversity” by bringing it to a level where actionable knowledge and effective practices are possible. It thus creates a new category (or expands old categories) of understanding to incorporate the type of change needed in business strategies.28

The term includes both the descriptive aspect (that stakeholder engagement is nature-based because it takes place in and depends on human-nature interaction) and the normative aspect (that stakeholder engagement should be nature-based because non-human actors should be stakeholders and because the biodiversity crisis makes this unavoidable in the end).

The concept of nature-based stakeholder engagement provides business leaders and stakeholders a basis for mental leaps toward creative actions, opening up an entirely new set of topics related to concrete actions affecting biodiversity.

References

1 “Global Biodiversity Outlook 5.” Convention on Biological Diversity, 18 August 2020.

2 “Half of World’s GDP Moderately or Highly Dependent on Nature, Says New Report.” World Economic Forum, 19 January 2020.

3 Locke, Harvey, et al. “A Nature-Positive World: The Global Goal for Nature.” Wildlife Conservation Society, 2020.

4 “What You Need to Know About Nature-Based Solutions to Climate Change.” The World Bank, 19 May 2022.

5 Kujala, Johanna, et al. “Stakeholder Engagement: Past, Present, and Future.” Business & Society, Vol. 61, No. 5, January 2022.

6 Hughes, Ian, Edmond Byrne, Gerard Mullally, and Colin Sage (eds.). Metaphor, Sustainability, Transformation: Transdisciplinary Perspectives. Routledge, 2022.

7 Kujala et al. (see 5).

8 Davies, Clive, et al. “The European Union Roadmap for Implementing Nature-Based Solutions: A Review.” Environmental Science & Policy, Vol. 121, July 2021.

9 Black, Max. Models and Metaphors: Studies in Language and Philosophy. Cornell University Press, 1962.

10 “Regenerate Nature.” Ellen MacArthur Foundation, accessed February 2023.

11 Chazdon, R.L., et al. “Partnering with Nature: The Case for Natural Regeneration in Forest and Landscape Restoration.” Forest Ecosystem Restoration Initiative, 2017.

12 “Nature Restoration Law.” European Commission, accessed February 2023.

13 Davies et al. (see 8).

14 The World Bank (see 4).

15 Muñoz, Pablo, and Oana Branzei. “Regenerative Organizations: Introduction to the Special Issue.” Organization & Environment, Vol. 34, No. 4, November 2021.

16 Hargreaves, Tom. ”Practice-ing Behaviour Change: Applying Social Practice Theory to Pro-Environmental Behaviour Change.” Journal of Consumer Culture, Vol. 11, No. 1, March 2011.

17 Boiral, Olivier, and Iñaki Heras-Saizarbitoria. “Managing Biodiversity Through Stakeholder Involvement: Why, Who, and for What Initiatives?” Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 140, April 2015.

18 “Respecting Biodiversity: Achievements 2022.” L’Oréal Groupe, accessed February 2023.

19 Hughes et al. (see 6).

20 Roloff, Julia. “Learning from Multi-Stakeholder Networks: Issue-Focussed Stakeholder Management.” Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 82, October 2007.

21 “A Guide to Biodiversity for the Private Sector.” International Finance Corporation, accessed February 2023.

22 Kujala, Johanna, and Sybille Sachs. “The Practice of Stakeholder Engagement.” In The Cambridge Handbook of Stakeholder Theory, edited by Harrison, Jeffrey S., et al. Cambridge University Press, 2019.

23 “Stakeholder Engagement is Key to Effective Conservation and Sustainable Use of Marine Biodiversity.” Research Institute for Sustainability, Helmholtz Centre Potsdam, 23 May 2022.

24 McCann, Liam. “The Business of Protecting Biodiversity — and Why It’s Your Business.” Neste, 17 June 2022.

25 “Positively Impacting Nature Through Biodiversity Protection.” Holcim, accessed March 2023.

26 “Protecting Biodiversity and Regenerating Nature.” Unilever, accessed March 2023.

27 Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures website, 2023.

28 Cornelissen, Joep P., Robin Holt, and Mike Zundel. “The Role of Analogy and Metaphor in the Framing and Legitimization of Strategic Change.” Organization Studies, Vol. 32, No. 12, November 2011.