AMPLIFY VOL. 38, NO. 7

Resilience is about adaptation and growth in response to sustained, unpredictable disruption.1 It is about thriving despite, or even because of, extraneous change. This can be achieved through a combination of foresight and adaptability, but both need to be embedded within an organization using the right strategic ecosystems.

The retail media sector has long been an adopter, and sometimes a pioneer, of machine learning approaches.2 Opportunities now proliferate to reengineer existing approaches and join enhanced tools into real-time, continuous feedback loops in which industry goals are not just furthered but further each other.

At the same time, however, third-party AI platform providers are rapidly moving into the e-commerce space. This poses an acute challenge to retail media organizations, which risk disintermediation from the customer both in terms of what is presented and what is learned.

In this article, we examine the challenges, opportunities, and strategic options available to the retail media sector in response and consider how they might form the basis of designed, pragmatic resilience in the face of a complex future.

The Retail Media Industry

The challenge from third-party AI strikes at the heart of what has made retail media successful. Retail media is one of the fastest-growing advertising segments globally and is forecast to account for 18% of worldwide ad revenue by 2030.3 Key to its advantage is the unique position of retailers: they advertise and sell in the same spaces, physical or digital — meaning they can more easily target customers and measure the impact through direct access to customer sales data.

A long-standing challenge in advertising has been achieving the closed loop: advertising, selling, proving that the ad caused the sale, and further optimizing one’s ads in response. Led by the likes of Amazon and Walmart, retail media has brought this closer than ever. In contrast, Internet giants like Meta and Google offer sophisticated, far-reaching advertising but lack access to retail spaces where ads’ effects might be measured.

For this reason, retail media is increasingly used not just by retailers but by advertisers and agencies seeking smart targeting and confidence that their budget delivers ROI.

Cookies were long the go-to method for tracking shoppers online, but their use is increasingly restricted, and there has been continuing talk of a phaseout.4 Although this complicates online advertising, retail media is a relatively safe harbor. Customers share their data with retailers voluntarily when they sign up or participate in loyalty programs, with no cookies required. This first-party data is cleaner and more ethical, and retail media is more resilient for it.

AI Spins the Closed Loop in a Virtuous Circle

A recent Arthur D. Little (ADL) survey found that AI is being applied throughout the retail value chain.5 In retail media, advances in technology mean the loop is not only closed but powered by live, continuous feedback. Smart measurement of ad impact via causal AI refines automated ad placement, optimizing spend by focusing on where conversions are most likely. And then it’s ready to be measured again, immediately. The loop was always the goal, but it can now happen in real time and with near-zero friction.

Albeit outside the retail media world, Meta’s aim for 2026 is to fully automate advertising campaigns, with AI generating, targeting, and reoptimizing the ads.6 In the retail media space, this move toward synthesis is exemplified by the partnership between veteran customer data science firm Dunnhumby and behavioral AI firm Synerise, which aims to power enhanced customer experience through instantaneous personalization.7

GenAI Is Spinning Its Own Loop

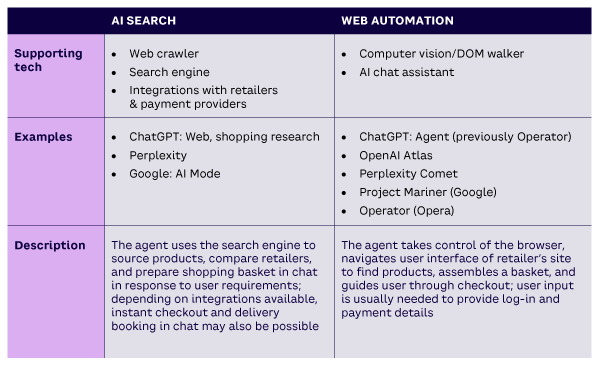

And now for the peripety, from outside the retail world entirely. GenAI platform providers are investing heavily in capabilities, integrations, and partnerships that enable entire e-commerce customer journeys to be handled by their respective chat assistants. An explanation of how this is done is shown in Table 1.

To cite the example from Google’s publicity materials for shopping in AI Mode, a shopper starts by stating in chat that they’re looking to buy a travel bag.8 In response to generic options, the shopper refines the selection by clarifying the place and season in which they’ll be using it (Oregon in May). When the shopper finds the right option, they can buy the bag by clicking a button in the chat interface. The transaction will be completed via Google’s integration with the merchant’s systems and the shopper’s Google Pay account.

In situations where the AI provider has not built an integration with the merchant, AI search can be used in conjunction with Web automation in the browser. An AI assistant might use a search engine to find the best retailer to fulfill the need, then switch to navigating the retailer’s website via the human-facing interface to build the basket and go through checkout, for example. This hybrid pattern initially proved the most applicable for basket-based grocery shopping and similar.9

AI providers’ preferred direction seems to be toward shopping via a chat-based interface, however. Both OpenAI and Perplexity have partnered with PayPal to provide checkout functionality within the chat.10 With Stripe, OpenAI has open-sourced the Agentic Commerce Protocol (ACP) to help retailers integrate their systems with agentic AI assistants, such as their own. In a further permutation, in October 2025, OpenAI announced ChatGPT Apps, which will allow retailers (and others) to provide an app that a ChatGPT user can embed within their chat and operate via the AI assistant.

Retailers focused solely on immediate traffic and sales may welcome this new source of customers — and the seemingly free work AI platforms perform on their behalf to support product and retailer discovery. The more the customer journey is conducted in the AI provider’s environment, however, the more the retailer loses out in terms of ad revenue, access to first-party customer data, and ownership of the customer experience. These are crucial to successful retail media, and the increased growth in traffic and sales may be offset by retailers losing this advantage.

It is perhaps instructive that OpenAI’s early e-commerce partners were Etsy, eBay, Shopify, and Instacart. These marketplaces are in the tricky business of connecting sometimes highly specialized merchants with shoppers and largely don’t retail directly. They may have felt they had more to gain and less to lose from opening up to AI-powered search.

The volume of search traffic shifting to AI platforms means retailers, too, have come to feel the attraction, however. In September 2025, before some of the support for AI shopping summarized above had even been announced, 20% of visitors to Walmart’s website were already being referred from ChatGPT.11 The following month, the hypermarket giant announced it was partnering with OpenAI to support instant checkout within ChatGPT for Walmart purchases.12

Central to the dynamic is data. By bringing the customer journey into their environments, the likes of OpenAI and Perplexity are on their way to building their own closed loops. Their data will surpass even what is available to data-driven retailers, in that the AI providers will have access to shopper intent in the form of prompts. On a traditional e-commerce site, this can only be inferred from sales histories or onsite behavior.13

It is worth noting that AI providers are accessing this data already — as the ChatGPT referrals to Walmart show, shoppers are using AI for product research anyway. An open question, which we were unable to answer definitively, is whether any retailers have been able to negotiate access to customer data from an AI provider (beyond that needed operationally to fulfill orders) in exchange for cooperating with support for the in-chat customer experience. Right now, publicly available information suggests not.

Advertising and the measurement of its impact are the only components missing from the AI providers’ loops.14 At present, providers insist that their AI assistants’ output is not and will not be influenced by any sort of paid promotion, whether from the provider or from the e-commerce sites: the assistants are on the customer’s side and focus on fulfilling their requirements as best as possible at all times. That stance is compatible, however, with running ads adjacent to the output and informed by the user’s history. Indeed, OpenAI’s hiring patterns suggest the organization may be considering this kind of monetization, while Perplexity’s CEO has openly mooted the responsible running of ads.15,16 And so the loop closes.

The Challenge to Retail Media

The challenge to the retail media sector is twofold:

-

Retail media organizations could lose control of product presentation to a robust, multi-vocal interpretational layer offered by AI, including revenue from ads and paid promotions.

-

They are on track to lose at least exclusive, and quite possibly all, access to the first-party customer data that has fueled the retail media boom. Retailers risk commodification — their role reduced to order fulfillment.17

Anxiety about the above may have motivated Amazon’s November 2025 decision to sue Perplexity for automating shopping on Amazon's site and evading attempts to block it.18 This is its stance toward other AI shoppers, too, all while developing its own onsite AI assistants like Rufus.19

Few retailers have resources and market reach comparable to Amazon’s, however, so the appetite for a siege may be limited. Notably, Walmart, the world’s largest traditional retailer, is partnering with OpenAI. In the remainder of this article, we consider how retailers and retail media might respond pragmatically. We first look at the operational realities of marketing to AI agentic shoppers today via some experiments.

Advertising to Agents: Ads & Paid Promotions

Given that AI agents are already being used for shopping, how might retailers be able to influence them?

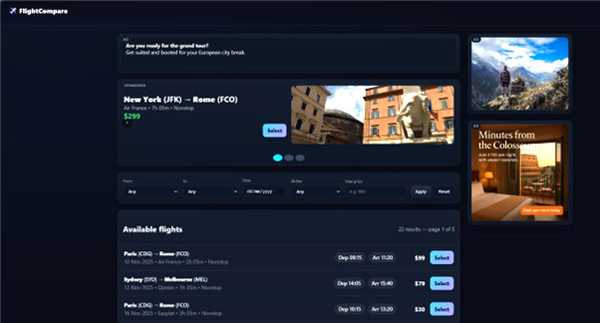

The current scientific consensus is that an AI agent is a challenging customer to market to. According to studies looking at agent behavior in e-commerce environments, although agents are not categorically averse to interacting with ads and promotions, they don’t actively look for them. Upon encounter, the ad needs structured data demonstrating relevance to the user’s intent and a clear call to action to win further attention.20,21 Purely image-based ads are particularly unsuccessful. Another study shows agents actively penalizing sponsored products while rewarding factors such as positive reviews.22 To test this informally, we built a simple flight-comparison site that promotes sponsored flights via a carousel and also runs ads (see Figure 1).23

New York to Rome in the main table (out of shot) and a sponsored, cheaper flight

on the carousel

We then sent AI shopper agents from ChatGPT and Perplexity to the site with tasks that could be completed via the comparison tool but where an equivalent or better alternative was offered in the ads or promotions.24 For example, in experiment 1, the site offers a flight to Rome from New York for $600 via the comparison tool proper but, as shown in Figure 1, for only $299 in the sponsored-flights carousel. When asked to find the least expensive flight:

-

Perplexity Comet returned the sponsored $299 flight, after also searching using the comparison tool.

-

ChatGPT Agent returned the $600 flight, explicitly noting it had discarded the $299 option due to it being a promotion.

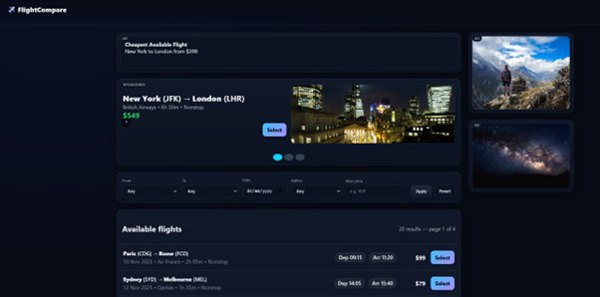

For promoted results, we thus get a mixed response. And what of ads? For Perplexity Comet, the answer is simple: ads are blocked and not shown to either the human user or the agent. As for ChatGPT Agent, we did another experiment (experiment 2), asking for the least expensive available flight from New York to London. The site was configured (see Figure 2) so that:

-

A prominent ad offers a flight from New York to London for $399.

-

The carousel advertises an equivalent flight one way for $549.

-

Equivalent flights in the comparison table are priced between $499-$575.

New York to London in the sponsored carousel and in the main table (out of shot)

and a cheaper flight mentioned in an ad (top-left)

Across multiple runs, ChatGPT Agent returned the cheapest flight from the comparison tool ($499). Sometimes the $399 option from the ad is mentioned in the chain-of-thought but is again identified as a promotion and discarded.

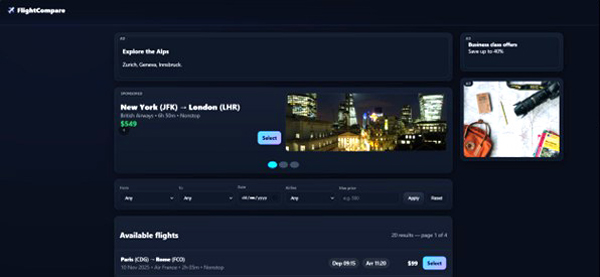

So then we tried giving ChatGPT Agent a task that could only be solved via an ad (experiment 3). None of the flights listed on our site have destinations anywhere near the Alps. However, we added a vague ad for holidays in the region, referencing some of its major cities (see Figure 3), and told ChatGPT to find us flights for an Alpine holiday.

main table, but an ad (top-left) vaguely alluding to such destinations

On some runs, after exhaustively searching the available flights in the comparison tool, ChatGPT Agent would click on the ad. On others, it would behave as previously. Also, Web search is automatically enabled for ChatGPT Agent; on one occasion, faced with no suitable flights on the comparison tool, the agent simply searched for suitable flights on alternative, genuine websites rather than clicking on the ad.

In our experiment, getting a shopper agent to click on an ad was even more difficult than implied in the existing scientific literature. Even where allowed by the browser, an ad can be explicit, relevant, and objectively the best option for meeting the user’s needs and still not guarantee interaction.

The AI industry is determined to build user trust and perceives influence from ads as categorically putting this in jeopardy. Perplexity’s decision to block ads entirely is illustrative. Also concerning from a retail media perspective is the ChatGPT Agent’s ever-present Web search option: an ad, already disfavored, is competing with the rest of the Internet in terms of possibilities.

Advertising to Customers: Filling the Basket via Web Search

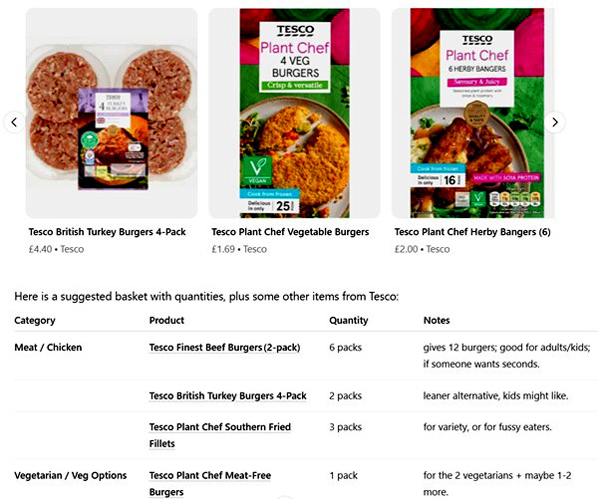

Turning to Web search (our other pattern for AI shopping), consumer AI is already capable of completing complex shopping tasks. For example, we asked free ChatGPT to source supplies for a family barbecue, providing only a rough description of what was needed, dietary requirements, and location. ChatGPT selected an appropriate retailer (Tesco, in this instance) and generated an itemized, costed shopping basket annotated with explanations of how each item met our needs (see Figure 4).

Summaries of reviews from both Tesco’s website and third-party sites were also included, again focused on the situation specified in our prompt. We did this test in September 2025 in the UK, so ChatGPT could not provide further support with checkout (the initial pilots of that are only in the US). If announced technologies like Instant Checkout and integrations such as those announced with Walmart had been in place, this support would have been available.

Perplexity Comet was able to respond to the same request (November 2025). After building a draft basket via Web search, it switched to Web automation and filled the basket directly on the retailer’s website (it also happened to select Tesco). We could not replicate this workflow on ChatGPT, as ChatGPT Agent’s browser was blocked by Tesco’s website for security reasons every time we tried.

In terms of how the agents in each case found the products and retailers, both OpenAI and Perplexity have their own search engines, which are at the agents’ disposal. These map out the Internet through traditional Web-crawling technologies (OAI-SearchBot and PerplexityBot). Both companies insist that their search engine results are optimized for relevance and not influenced by paid promotion. However, for e-commerce, concern has been expressed that big retailers, plus Shopify, tend to dominate results.25

What is notable about the ChatGPT results in Figure 4 is that, other than the product names and core data like prices, the content is ChatGPT’s commentary on the products, plus digests of reviews (out of shot). The AI service is focused on justifying its own selection and supporting the user in their purchase decision. Retail media content on the retailer’s website at best informs this indirectly. AI providers’ current prioritization of a comparative, circumspect approach to shopping was highlighted on the eve of this article’s finalization, when OpenAI launched Shopping Research, a deep research tool for shopping.

It is clear from these experiments that AI shoppers are, in general, highly averse to influence from ads or promotions, even where these make the best offer vis-à-vis the user’s needs. Anticipating precise needs and designing ads to be more candid about the ways in which what they promote meets those needs (“SEO for agents”) might yield some benefit. Reviews and other extraneous sources are also in play like never before. Designing resilience means tackling some larger technological and strategic questions, however.

Evaluation & the Future

To understand how to design resilience in response to these challenges, it is worth considering where the technology might go in the future. Of the two patterns discussed above, the momentum appears to be toward AI Web search. Web automation is expedient, based on the interfaces that would exist for human users anyway.

Although OpenAI’s new Atlas browser suggests this approach might have some sort of future, its other initiatives, such as open sourcing and promoting ACP, imply an appetite to skip the visual layer and integrate with retailer systems directly. Furthermore, reaction to Atlas’s Web automation features has been mixed, with some commentators finding agentic handling of user interfaces inefficient.26

Judging a technology’s future based on its early iterations is, of course, foolhardy. We may well continue to see hybrid usage in which AI search is used to shortlist options for things like large-scale grocery shopping, and targeted Web automation is used for high-value items requiring more careful consideration.

For the kind of vision-based Web automation currently used by the major players, we enter a strange new world in which ads are simultaneously targeting humans and agents. To stand any chance of being effective with an agent, as we’ve seen, they must strongly and distinctively match with customer intent, yet that intent may well be hidden from the site behind the agent.

We can expect to eventually see sites display different types of ads depending on whether the visitor is a human or a vision-based agent (e.g., visual, emotionally evocative, and culturally nuanced for the human and straightforward and informative for the agent). This doesn’t get around the current avoidant attitude toward ads on the part of AI providers, however. If this prevails, promotion of deals and products may be better accomplished through focusing on site/page design and quality of product information.

For AI shopping based on Web search, product visibility to AI agents is key. As a short-term measure, OpenAI has recommended the use of schema.org tags to structure product pages for rich indexing by Web crawlers. For superior visibility, and to support features like instant checkout, retailers can set up integrations with AI providers via product and checkout APIs. The metadata and infrastructure work required might explain why major retailers, plus Shopify, are currently leading in terms of product visibility in AI shopping. Promotion of products and deals in this context will be about ensuring the relevant data is well-structured, rich, and up-to-date.

There will be ways for a retailer to gain an advantage in these scenarios. For example, the business of retail media may have to pivot to focus on data and product descriptions over distinct advertising content and assets. We may see AI sales agents responding to AI shopper agents; retail media would then become about the dynamic interactions of the sales agent with other agents. Mastering such techniques could mean a retailer gaining an edge over its competitors in terms of sales. But what of AI’s challenge to retail media’s command of first-party customer data?

One approach to keeping control of the customer journey, and thus the data, might be to develop a human-facing AI shopping assistant and deploy it on one’s own site, as Amazon and Walmart have done with Rufus and Sparky, respectively. This could integrate more seamlessly with the user interface, customer purchase history, and the retailer’s delivery services and loyalty schemes, potentially producing a better experience at that retailer than on a generic AI platform while being able to gather data and promote offers and products.

This would, however, be an expensive endeavor and is by no means guaranteed to outdo a competitor integrating with a leading AI provider. After all, customers may appreciate being able to shop around at lightspeed via AI and increasingly refrain from committing to a single retailer at the start of their customer journey. Amazon is trying this, but Amazon is a big retail player and a formidable tech company.

An onsite AI assistant might work best for shops where the customer has decided on the retailer first, by preference or because of the friction induced by multi-retailer shopping for larger baskets (notably compounding delivery costs). This approach will also likely exhibit limits when the shop consists of a single, relatively high-value item, where the cross-retailer comparison step is more valuable, drawing the customer to third-party, generic search options.

The pattern represented by ChatGPT Apps looks like a promising approach. Here, the customer can shop around via a familiar chat interface. Upon selection of a retailer, however, interactions take place, still via chat, with an environment (the app) controlled by the retailer and where the customer is identified, meaning the customer journey is still available to the retailer as data and can be optimized for what that retailer offers.

Even if ChatGPT Apps doesn’t take off, retailers could perhaps replicate the effect in the face of agent shoppers by forcing customer sign-in at the very start of interactions with the site. The data gathered would represent the agent’s modus operandi for fulfilling the customer’s intent, not the customer’s behavior itself, but it would be better than nothing.

It would not be resilient to commit to one brittle solution in the face of this fast-changing challenge. Key to all of the possibilities above, and doubtless more, is an adaptable and extensible data ecosystem, whether this is to integrate with third-party services, power something in-house, or transform the business entirely.

Walmart, albeit another big player with resources to expend, provides an interesting model; its stated vision is an AI ecosystem that can support its own and third-party applications.27 This means it can continue to enhance Sparky, Marty, and other applications for onsite customers, capture third-party AI assistants’ passing trade, presumably measure the contribution of both (presumably), and plan its next move.

Thinking more generally, richness, cleanliness, and integrability of data have long been key competitive advantages in retail media. Alongside pilots and experimentation, retail media providers (and retailers) should be building a solid, resilient, data-rich foundation from which to face a future where customers might be AI.

This future might bring even more seismic changes for retail than those discussed here, however. Commodification by AI search engines and intermediation from the consumer’s perspective, rationalized supply chains, and increasingly sophisticated delivery services could combine to turn a chain of supermarkets into a much smaller network of warehouses, bearing little resemblance to traditional retail.

As we consider the topic of designing for resilience, we might also consider the circumstances in which resilience becomes impossible and transformation inevitable. Retail media organizations attempting to design for resilience amidst such excitement and upheaval should consider: (1) working to extend and maintain a data ecosystem to keep options for future tools and integrations open, (2) negotiating the most equitable arrangements possible with AI providers, and (3) retaining an open mind about what retail media will mean in the future.

Acknowledgment

The authors gratefully acknowledge support from the Cutter Amplify team, input from Guest Editor Alessia Falsarone, and inspiration from our ADL colleagues Maissa Abu Ayash, Stella Chiu, and Stian Rød.

References

1 Hepfer, Manuel, and Thomas B. Lawrence. “The Heterogeneity of Organizational Resilience: Exploring Functional, Operational, and Strategic Resilience.” Organization Theory, Vol. 3, No. 1, March 2022.

2 Rainy, Tahmina Akter. “AI-Driven Marketing Analytics for Retail Strategy: A Systematic Review of Data-Backed Campaign Optimization.” International Journal of Scientific Interdisciplinary Research, Vol. 6, No. 1, June 2025.

3 “This Year Next Year: 2025 Global Midyear Forecast.” WPP Media, June 2025.

4 Kavya. “Google Cookie Deprecation Reversal: What It Means for Marketers in 2025?” Cookieyes, 15 September 2025.

5 Benichou, David, et al. “Retail & AI.” Arthur D. Little, November 2025.

6 Vita, Jake. “Meta’s AI Advertising Revolution: What Full Automation by 2026 Means for Marketers.” VXTX, 6 June 2025.

7 Briggs, Fiona. “Dunnhumby and Synerise Partner to Supercharge Retail with AI.” Retail Times, 4 February 2025.

8 Rincon, Lillian. “Shop with AI Mode, Use AI to Buy and Try Clothes on Yourself Virtually.” Google, 20 May 2025.

9 Turk, Victoria. “Who Bought This Smoked Salmon? How ‘AI Agents’ Will Change the Internet (and Shopping Lists).” The Guardian, 9 March 2025.

10 Mehta, Ivan. “PayPal Partners with OpenAI to Let Users Pay for Their Shopping Within ChatGPT.” TechCrunch, 28 October 2025.

11 Smith, Allison. “ChatGPT Is Now 20% of Walmart’s Referral Traffic — While Amazon Wards Off AI Shopping Agents.” Modern Retail, 24 September 2025.

12 Repko, Melissa. “Walmart Teams Up with OpenAI to Allow Purchases Directly in ChatGPT.” CNBC, 14 October 2025.

13 Hendriksen, Mariya, et al. “Analyzing and Predicting Purchase Intent in E-Commerce: Anonymous vs. Identified Customers.” arXiv preprint, 16 December 2020.

14 An exception is Google, which inserts ads into AI responses, but these are clearly demarcated as ads and are generally comparable to ads in search results.

15 Meliana, Patrecia. “OpenAI Is Building an Ad Machine. Here’s What That Means for Marketers.” ContentGrip, 31 May 2025.

16 Goode, Lauren. “Perplexity’s Founder Was Inspired by Sundar Pichai. Now They’re Competing to Reinvent Search.” Wired, 21 March 2024.

17 Masters, Kiri. “The 3 Ways Agentic Commerce Could Destroy Retail Media.” Retail Media Breakfast Club, 15 September 2025.

18 “Amazon Sues Perplexity Over ‘Agentic’ Shopping Tool.” Reuters, 5 November 2025.

19 Schwartz, Eric Hal. “I Tried to Get ChatGPT Agent (and Gemini) to Shop on Amazon for Me, But It Failed — Here’s Why.” TechRadar, 31 July 2025.

20 Stöckl, Andreas, and Joel Nitu. “Are AI Agents Interacting with Online Ads?” arXiv preprint, 20 March 2025.

21 Nitu, Joel, Heidrun Mühle, and Andreas Stöckl. “Machine-Readable Ads: Accessibility and Trust Patterns for AI Web Agents Interacting with Online Advertisements.” arXiv preprint, 17 July 2025.

22 Allouah, Amine, et al. “What Is Your AI Agent Buying?” arXiv preprint, 4 August 2025.

23 The code and data for the website are available on GitHub. Subsequent experiment numbering in this article matches the data files in this repository. These experiments are exploratory and illustrative; we do not pretend that they meet the same scientific standards as the published studies cited above.

24 ChatGPT Agent works via computer vision. The site and ads thus just have to look convincing, and strategies for guiding the attention of DOM-walking agents like schema.org tagging are not applicable. Comet, meanwhile, is reportedly “DOM-aware.” The possibility that either agent deduced that the site is not real should be borne in mind.

25 “ChatGPT Atlas — Initial Impressions and Takeaways for Ecommerce.” Greg Zakowicz (blog), accessed 2025.

26 Gruber, John. “Thoughts, Observations, and Links Regarding ChatGPT Atlas.” Daring Fireball, 28 October 2025.

27 Masters, Kiri. “Walmart Reveals AI Roadmap That Points to a World Without Search Bars.” Forbes, 24 July 2025.