AMPLIFY EXECUTIVE UPDATE VOL. 37, NO. 1

A Voice of Success

If you are engaged in any form of an Agile or digital “transforming” journey,1 you need to know about Jeff Smith. Smith has worked as CIO, COO, CEO, and board member of companies from start-ups to the Fortune 50. Beginning in the mid-2000s as CIO of Australian telecom Telstra, he was named the most influential IT executive in Australia for a decade. From his C-suite seats, Smith led three large-scale Agile transitions, including one at IBM (IT staff of 25,000), each driven by a time-critical business need.

Often defying conventional wisdom, Smith’s approach to the Agile journey is worth your time to understand. It evolved over a storied 40-year career, always balancing performance (outcomes) with people (organizational health). His transforming strategies included:

-

Communicate purpose simply and clearly — communicate the “right” things well.

-

Operationalize and mandate culture change from the top down — mandate behaviors to change mindsets.

-

Radically reform middle management layers — reduce the Bureaucratic Mass Index (BMI) to <15%.

-

Modernize delivery from the bottom up — increase talent density, especially engineering talent.

Smith had a dream:

[I wanted] to see if I could create a culture at Suncorp that had the innovation of the best tech companies and the scale and opportunity of a large bank/insurer. We developed a concept called “operationalizing culture.” We wanted to make an Agile culture something you could learn, practice, measure, and improve. Our strategy was to break culture up into a set of practices, measure the maturity of those practices across the company, and then make course corrections and improve.

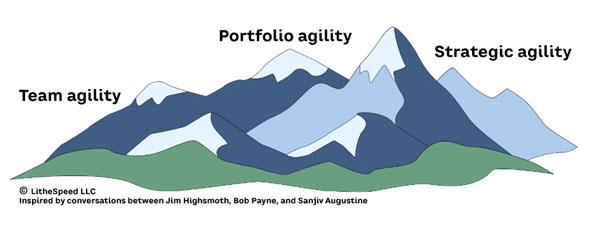

The purpose of agility is simple: to prepare individuals and organizations for our turbulent future. But to paraphrase the old saying, “Agility is easier said than done.” Preparation includes honing your ability to sense and respond (see Figure 1). To prepare for the turbulent future, agile-adaptive leaders must:

-

Balance between performance (outcomes) and people (organizational health).

-

Seek adventure, proposing challenging initiatives that are risky but not foolhardy.

-

Articulate an inspiring vision that engages others to implement that vision.

-

Be adaptive, embracing an envision-explore mindset: quick to sense, act, and adapt by looking at reality, whether it conforms to earlier plans or not.2

Agile speaks to flexibility and resilience; adaptive reflects an iterative process (sense, act, adapt). Together, they define an agile-adaptive mindset. Consider these traits as we hear about Smith’s leadership of several large Agile transitions.

This Update explores Smith’s approach to Agile transforming, his achievements, and his disappointments over many years with three organizations. Will his approach work for everyone? Of course not. Every enterprise is different, but we can learn from his experiences. The sections on strategies describe their current state, rather than each of the changes occurring over time. The sections on each organization emphasize the challenges Smith faced at each one, along with his accomplishments and disappointments.

Communicate Purpose Simply & Clearly

It’s hard enough to execute a strategy when it’s simple; it’s impossible when it’s complicated.

— Smith

Simple, clear, objectives are key to getting your entire organization behind a change. Instead of having 10 concurrent strategic objectives, pick three, get those done, then go on to the next three:

If you’re going to scale something, your messages have to be simple. They’ve got to be clear. You must know the hill you’re going to take, and you have to make it tangible for employees.

— Smith

Phil Abernathy began working for Smith as his executive transformation consultant at Suncorp. At that time (2007), Australian companies had little experience with scaling Agile, and companies elsewhere didn’t have much more. Leading-edge Agile transformations were happening at Salesforce in the US, but each effort was homegrown. Abernathy and Smith evolved their approach to transformation together, and when Smith went on to IBM and World Kinect, he hired Abernathy to lead those efforts. The focus of this Update is Smith, but success was (as always) a collaborative effort. Abernathy and I talked about Smith’s approach to simple, clear communication:

You have to understand that to communicate clearly and effectively, finding the root problem to solve is the first step. I’ve met many great leaders who are in senior positions who communicate succinctly but are not effective as they have missed, or don’t address, the core problems.

That is Jeff’s magic. He knows that every company is different and can put his finger on their core problems. From this unique ability, two or three stretch goals, the BHAGs [big hairy audacious goals] to communicate would emerge. Here’s the trick with Jeff: he does not change the message. He’s repeat, repeat, repeat. If the message is changed or the leader wavers at the first sign of push back, the change is doomed. Jeff hung in there with confidence and conviction.

— Abernathy

Smith adds his perspective:

You need goals that are highly aspirational that you don’t know how to solve. Most companies make a mistake when they set a goal; they want to know up front how to get there. Well, you don’t know that. You’ve got to let the innovators determine how the heck we’re going to do this.

Smith’s ideas about clear and simple communication would be tested at Suncorp, the first of his Agile journeys in a large organization. To underline one of Smith’s points: if you know how you are going to accomplish a goal up front, it’s probably not audacious enough.

Suncorp

Smith arrived as CIO at Suncorp, a large bank/insurer in Australia, in March 2007, just in time for the fallout from the Great Recession of 2007–2009. Although the Australian economy did not go into recession, its banking industry suffered. Suncorp was a banking and insurance business with around 18,000 employees, 5,000 of which were in IT.

When Smith arrived, Patrick Snowball, the new CEO, wanted to focus IT on three things: (1) geocode the country, (2) price insurance at an address level, and (3) consolidate 18 claims systems into one. The CEO envisioned a strategic integrated platform that would service customers online and consolidate operations, saving AUD $350 million. He asked how long it would take. After deliberation, Smith said development would take four years. The CEO asked how it could be done in two:

So what did we need to do the Suncorp project in two years? We would have to scale up, and there were not enough people in Australia who knew how to do that. The CEO asked how we would overcome that. It was one of my four big inflection points because I had come out of running a little start-up where I was introduced to Agile methods. I said, “Well, we’ve set up Agile squads and product owners, but that’s only with our own people. We’ll have to pick partners offshore to scale to enough staff.”

We picked up firms in India and China. We gave each of them a major system. We set all partners up the same way, even the desk arrangement. There were no collaboration environments at that time, so it was 24/7 Skype on TVs, and we paid by squad to makes things simpler. We measured them on cycle time, in WIP and lead time in the backlog, and velocity — the same way we managed our own squads. I still say 95% of the companies don’t do that as well today. One consulting company had a dual role: they had to build the digital platform while helping us with Agile practices across all of the partners and ourselves. Getting each of the distributed teams working with the same operating model was key to our success. It was hard to get through because everyone had egos. The other partners were waterfall. My response was, “If you want to work on this project, we are using distributed Agile, and you’re going to do it our way.”

It was amazing that we delivered the systems in just two years. Our learning went up, our cycle time went down, and our velocity more than doubled. We tackled things concurrently, getting rid of idle time and making sure we did a good job managing the backlog. With teams in India, China, and Australia, we pioneered distributed Agile at a time when remote collaboration tools were just emerging.

— Smith

Tony Ponton was a Suncorp insider, having spent 21 years of his career there. He was part of the Agile coaching staff that turned Smith’s vision into reality. Ponton’s Agile journey began in the early 2000s when an “experimental” group had success with Extreme Programming (XP) and continuous delivery. Of course, in that era, the organizational antibodies arose to throw cold water on the experiments. It wasn’t until Smith arrived that these underground Agilists began resurfacing:

Jeff arrived in 2007, and at that time, I wasn’t really on the Agile coaching staff, but we wanted to do projects in an Agile way. We came up with a prototype of mobile phone banking, and it caught Jeff’s notice. Jeff took the project to the CEO’s office saying he had to see this. The CEO was impressed and asked how long it would take to deliver it. When Jeff said six weeks, we fell off our chairs.

— Ponton

The mobile phone project preceded the huge platform development project and demonstrated the use of Agile practices. However, making the jump from a single team, six-week project to a large-scale rollout with teams distributed across three continents demonstrated what I’ve called “courageous executives,” which could be applied to both Smith and the CEO.

The mobile phone project was one of the Agile projects that the reformed IT org undertook. Its pace and success were stunning, and that’s why it stood out.

— Abernathy

That was Jeff for you. He started the Agile journey saying we’re going to go the Agile way. A lot of people forget that we were the first bank in Australia to introduce mobile phone banking. We beat all the majors to the punch because Jeff took a risky bet, and I’ve got to tell you, the thing we put out in six weeks was ugly as hell, but we beat everyone else. It was the same with Internet banking. When everybody else was buying banking solutions, we built internally. That put Suncorp in control of its critical online banking infrastructure.

— Ponton

Delivering the large platform system in two years and the mobile banking system in six weeks demonstrated the viability of Agile practices, and it became a core capability at Suncorp. But it wasn’t successful everywhere. Abernathy thought a big disappointment at Suncorp was that Agile practices were not adopted outside Smith’s organization:

It was a phenomenal success; the whole of Australia was talking about Suncorp. We were the first major company to run a transformation at that scale. In Australia, we were at every conference, people were visiting us from all the big banks to see how great we’re doing. Yet in other departments (finance, marketing, product, insurance claims), no one wanted to touch it. The not-invented-here syndrome kicked in. That was a big disappointment.

— Abernathy

Ponton had an interaction with Suncorp staff a couple of years later:

I went back to help them again. And the interesting thing is that agility was still there. Jeff had built that grassroots agility into people, and there were enough people left in the organization that still were holding on to it. They’re now doing a reboot of the Agile transformation with a CIO and CEO who both knew about Agile.

Smith’s seven-plus years at Suncorp began during a worldwide economic crisis. His successes during these years (implementing a large platform product in record time, pushing the company into mobile and Internet banking early, moving applications to the cloud, and creating an Agile culture throughout the IT organization) led to his stellar reputation in the Australian IT community and, eventually, to a hot-seat position as IBM CIO.

Operationalize & Mandate Culture Change from the Top Down

Make your culture tangible and mandatory — don’t give people an out. Initially, I made using Agile practices voluntary, thinking everyone would want to be more productive. I was wrong.

— Smith

Smith’s strategy was to operationalize culture from the top down while building delivery capability from the bottom up. Some people think you must first change beliefs (mindset) to change behavior. I think you can change behavior in such a way that it leads to belief change. You can’t mandate beliefs, but you can mandate behavior in the form of specific practices. Implementing practices the right way leads to belief changes, creating a virtuous cycle:

It’s easier to act your way into a new way of thinking than think your way into a new way of acting.

— Jerry Sternin, Harvard Business School

People might say that mandating is anti-Agile, because Agile is supposed to be collaborative and empowering, but sometimes as an executive or a leader, you must tell people what to do to get going. Smith’s idea was to mandate behavior in the form of 30 Agile practices, then institute a process of constant feedback and learning to get better (discussed in the “Modernize Delivery” section below).

Abernathy agreed that was his and Smith’s rationale:

Absolutely. That’s what situational leadership is about. Jeff cut through the mumbo jumbo by setting the scene and setting clear guardrails. And within the guardrails, you had autonomy.

Because historic management concepts like command-and-control were decidedly performance rather than people-oriented, modern concepts like empowerment, empathy, and servant leadership have become popular. In many instances, particularly in the Agile movement, the balance has shifted too far away from performance. Mirroring the Agile Manifesto, the phrasing should be “agile-adaptive over command-control,” not “instead of.” Smith’s approach results in a better balance between performance and people.

According to Carol Dweck in Mindset: The New Psychology of Success, about 60% of the population have a “fixed” mindset and 40% have a “growth” mindset. For the purposes of this Update, we can say that growth-mindset individuals are more open to change. In any organization, the mix of fixed to growth mindsets will impact how to approach culture change:

Mindsets frame the running account that’s taking place in people’s heads. They guide the whole interpretation process. The fixed mindset creates an internal monologue that is focused on judging.

— Dweck

Over time, especially in large organizations and those driven by financials rather than products, the ratio of fixed to growth mindset individuals tends to increase. Thus, initiating change often requires a dual approach: creating an inspiring vision and mandating early behaviors.

Culture is the only unique thing companies have. Most other things, like strategies and products, can be copied. If we want to be able to borrow learnings from other cultures or improve our own, we need to make culture tangible.

— Smith

IBM

In late 2014, Smith became IBM CIO and was tasked with bringing an Agile culture to its 25,000-person IT staff and more broadly within IBM. He was first introduced to Ginni Rometty, soon-to-become CEO (see previous Amplify Update), when Suncorp’s platform project included an IBM team from China:

We trained IBM China to use small squads, loosely coupled but tightly aligned by Agile practices. Those teams won innovation awards. Ginni met me in Singapore and asked why their China team was so successful. I responded that we had embedded the Suncorp culture into the IBM team and thereby produced much better results in employee retention, engagement, and productivity. She asked if I thought I could scale that at IBM. I thought yeah, probably. At the time, I had no intention of moving back to the US, but seven months later, there I was.

— Smith

Rometty had three strategic beliefs for IBM:

-

IBM must completely reinvent itself without losing its core identity.

-

Knowing what to change and what must endure asks us to think critically and solve problems.

-

If businesses don’t change, they cease to be relevant. But like a person, a business can’t change so much that it loses its soul.

Rometty recruited Smith to lead the Agile part of the transition to an Agile/design thinking culture at IBM. She believed IBMers had to quickly evolve to keep up with customers and the pace of change in the world. “Only two out of 10 IBMers had the tech skills and knowledge we needed for the company to move forward,” Rometty writes. And the price tag wasn’t cheap. Over the ensuing decade, IBM spent US $5 billion to revitalize its skills and jobs. “Together, design thinking and Agile provided the systemic work, behavior, and cultural changes we desperately needed,” Rometty recounts.

As an example of things to come, Smith took a sledgehammer to cubical walls in one building — moving from individual cubicles to collaborative workspace. But changing the entrenched culture wasn’t easy:

The biggest issue I had to overcome at IBM was the existing culture. IBM’s culture drove the love of the rank of position over the love of craft. IBMers were conditioned to look for opportunities to become executives because of the entitlements that came with those positions.

— Smith

At IBM, Smith and Abernathy updated their Agile playbook and instituted a comprehensive Agile training program based on what they had done at Suncorp. But they needed a hill to climb:

Early on, I needed to bring purpose to my squads. We needed a big problem to solve on behalf of all IBMers. We decided to tackle creating a productive work environment. For example, Apple Macs weren’t allowed because they were $400 to $500 more per unit. IBMers were dissatisfied with their PC support environment and wanted something different and modern. This was our big hairy problem to solve.

We started a Mac at IBM program, branded Mac@IBM. Across several hundred thousand personal computers, $400 each was a lot of money, so the squads had to figure out how to treat a laptop like a mobile device. Ultimately, we worked with Apple to codevelop a way to provision and deploy Macs with zero touch that made the cost equivalent to PCs and enhanced employee experience.

— Smith

IBM’s software collaboration tools were also out of date. Mac@IBM had gone so well that the entire collaboration environment was upgraded, including Box@IBM and Slack@IBM.

I asked Smith what he considered to be his other main accomplishments. He said:

A big one was taking large groups who were building systems that do the blocking and tackling to form 10-person, cross-functional squads. The squads could handle everything from managing the backlog through design, build, test, deploy, and support. This change happened in product groups across the company. Our metrics keep getting better at a faster rate than anyone thought possible. Give people good education, good support, good tools, and don’t underestimate their ability to learn. Another clear strategic hill was daily delivery on everything. I didn’t want any ugly stepchildren because people would say, “You can’t do this on mainframe systems” or “You can’t do it in older technologies.” We busted that myth.

Smith’s disappointments centered around the organizational and cultural barriers that retarded progress, even with the support of the CEO. His experience should serve as a cautionary tale to others on a similar journey: everyone — from delivery team members to the CEO — has constraints on their actions.

Smith and Abernathy honed the lessons they had learned at Suncorp, scaling from a large company to a huge one. Rometty and Smith started turning the IBM ship’s product lineup and culture toward a more agile-adaptive one.

Modernize Delivery from the Bottom Up

Smith concentrated on modernizing delivery by focusing on talent density and creating a healthy culture. His strategy for modernizing product delivery was four-fold:

-

Develop an Agile playbook of practices for leadership, collaboration, and engineering.

-

Organize teams into cross-functional squads.

-

Provide effective training and coaching.

-

Engage team members that care about their craft and are willing to practice/build skills both individually and as a team.

-

Select coaches that train, give advice, and course correct.

-

-

Develop an Agile maturity assessment (AMA).

Develop an Agile Playbook

Smith, Abernathy, and their team developed an Agile playbook of 30 or so practices divided into leadership, collaboration, and engineering components (see Figure 2). The playbook was a physical book (later online) that covered language, practices, and role expectations for each phase. It evolved over time by focusing on an idea-discovery-delivery lifecycle. Having the playbook, plus training, plus coaching worked well as they scaled Agile within the organization. The playbook focused on foundational or core practices and didn’t try to cover every contingency. Teams could add practices outside the core as needed.

Leadership practices included forming teams, flowing work, and measuring what mattered. Collaboration practices included daily standups, retrospectives, and Agile planning. Engineering practices included branching and version control, configuration management, refactoring, test-driven development, and DevSecOps (development, security, and operations). These practices evolved over time:

I think we were able to bring in an Agile culture and operationalize it for teams. Our concept was: Can we break culture into practices? Into something that we can train people on, coach them on, measure, and have them can get better at? It wasn’t punitive, this was about learning and a thirst for getting better. At first, everyone worries they’re going to be fired. Then they start to look at it as trying to get better.

— Smith

Organize Teams into Cross-Functional Squads

Forming productive squads is probably the most critical dimension of a leader’s job. Ensuring the squads3 have the right skills, chemistry, and diversity of thought, gender, and race is critical.

— Smith

Many of Smith’s ideas about teams came from the Spotify model and observing soccer teams. Smith said: “At Suncorp, we used soccer teams’ ideas of spending 70% of our time focusing on creating the right team and matching our strategy to the strengths of our teams.”

Smith and Abernathy began using soccer as a metaphor for how teams should be organized and led:

-

Match strategy to the strength of the team.

-

Keep score to get better.

-

Keep the team together so it gets better as a team.

Smith deployed his version of the Spotify organizational model, deploying squads (teams) at the lowest level. Squads were viewed as long-term groups focused on value streams or products.

The Agile Maturity Assessment

The playbook was accompanied by a simple, but effective, assessment tool:

I had a goal of being able to visit any squad and have them describe the maturity of their culture with tangible measures. We developed an Agile maturity assessment. It was essentially a traffic-light assessment of the 30 key Agile practices. We did this every quarter, with each squad self-assessing its maturity on a scale of one to five, and Agile coaches moderating the results to ensure consistency. At the beginning, squads were not strong in most practices (e.g., continuous delivery). Once they saw we were only concerned about them improving (not what their scores were) they gained skills by seeking constructive feedback and learning from others.

— Smith

Metrics are all about the leader’s “intent,” as author Kim Scott (Radical Candor) explains in a LinkedIn post:

There’s a world of difference between development (helping people grow in their careers) and performance management (rewarding good results and penalizing bad results.) Yet the two are often conflated. Giving a person a performance rating that translates to a bonus is very different from having a series of weekly impromptu guidance conversations that help a person develop the skills they need to succeed.

— Scott

Unfortunately, most of the productivity metrics used by Agile teams begin as development metrics but after a time slide into the performance category. Leaders must be careful because the intent of any metric will be quickly recognized (as per the old saying, “If you measure lines of code, you will get lines of code”).

The AMA is a development measurement. Abernathy and Smith also focused on three performance metrics:

Quality, speed, and throughput. We focused on those three first. Then we measured two other things: customer and employee satisfaction, which gave us a balanced scorecard. There were some DORA [DevOps research and assessment] metrics that came in later.

— Abernathy

Provide Effective Training & Coaching

The modern workplace’s most notable feature may be its lack of engagement and its disregard for mastery.

— Daniel Pink, Drive (emphasis mine)

One of Smith’s key strategies was developing talent. He didn’t just say, “We are going Agile,” he backed the initiative with significant investments in training and coaching. He brought in the best and the brightest to help increase knowledge and expertise internally. At Suncorp, he brought in Abernathy, who had been the head of ThoughtWorks Academy. Smith and Abernathy established an Agile academy within Suncorp that produced a role-based curriculum of 17 courses covering Suncorp’s Agile playbook. They instituted a one-day “Taste of Agile” course that everyone at every level (including the CEO) attended:

The reason we had to do the Taste of Agile was because attendees would walk out understanding basically what Agile was, why we were doing it, and our language around agility because we have specific ideas around that. Every employee had to attend that course.

— Ponton

Smith also understands the critical nature of software engineering and having excellent technical talent. His idea of talent density contains a heavy dose of engineering density:

You have to know your craft. You have to love your craft. You have to practice it as an individual and with your team. It’s not a program we shove down people’s throat. You want help? Here are the courses. You want coaching support? We will support you. We’re going to measure the team’s Agile maturity every quarter and post it. It’s to help people understand if they’re getting better. The whole focus is on how we can get better.

— Smith

Some of Smith’s squad-building ideas seem old hat in 2024. But remember, he began doing this in 2007. More than 15 years later, many organizations have failed to fully embrace this emphasis on long-term product-delivery teams.

When specific expertise was needed (e.g., DevOps, AWS, Agile practices), Smith’s strategy was to bring in the best of the best, opting for less-well-known, up-and-coming partners rather than well-known ones. In contrast to many of his peers, he believes that being on the cutting edge, in turbulent times, comes with less risk, not more:

You are the company you keep! Work with people you aspire to be like. Find the best-run companies and work and learn with them.

— Smith

Abernathy adds:

Jeff’s focus is about getting in engineering leaders. In most of the companies, especially in IBM, most of the first-line and second-line leaders were not engineers. If you look at Google and tech companies, their leaders are engineers.

If Agile leaders are trained and know their craft, they should be doing the coaching at the grassroots level. Jeff always held his direct reports accountable for transformation, rather than having a separate head of transformation.

World Kinect Corp

As a global energy management company, World Kinect Corporation (formerly World Fuel Services), headquartered in Miami, Florida, USA, offers a suite of energy advisory, management, and fulfillment services; digital and other technology solutions; and sustainability products and services across the energy product spectrum. In 2017, Smith became COO and senior VP, responsible for global operations in both IT and non-IT.

Smith’s BHAGs were:

-

Revamp both technology and delivery within World Kinect — transition to an Agile culture; demonstrate success by moving to the cloud

-

Streamline operations

One of Smith’s greatest strengths is his ability to delve into an organization and determine a high-value goal for his newly formed Agile teams to attack. At World Kinect, the goal was saving millions of dollars and streamlining operations by moving everything to the cloud (thereby closing 23 data centers). The goal wasn’t closing 21 or 22 data centers; it was closing all 23:

There was no ambiguity. Everyone knew exactly what that meant. And it forced us to think, “Well, we’ve got to get the networks out of the data centers.” We had 80 PBXs around the world. We’ll go to Zoom phone. We had AWS migrations. But had we not had that clear goal, we would’ve never accomplished what we did. There was no ambiguity.

— Smith

Agile squads were established, trained, coached, and put to work on this critical goal. Streamlining company operations included introducing Agile ideas to the entire leadership group and engaging them in the organizational redesign. The details of this effort are included in the next section about radically reforming middle management.

Smith’s journey at World Kinect shows an ability to learn and adapt, one of his seven measures for leaders. What he, Abernathy, and others learned at IBM and Suncorp led to important adaptations at World Kinect. As Smith quipped, “I wish I’d thought of these things back then.”

Radically Reform Middle Management Layers

Smith used three strategies to reform middle management:

-

Design an Agile operating model to give teams clear autonomy and accountability.

-

Reduce the BMI to <15%.

-

Reduce layers of middle management that blur communications and alignment between the top and bottom of the organization.

-

Dramatically reduce “enabler” groups like strategy, architecture, and project management offices.

-

-

Convert traditional managers into Agile leaders.

Design the Organization

Smith’s approach to scaling differs from most others in that he is willing to trade off potential efficiency for increased accountability and innovation:

The conventional wisdom was to start at the top of the organization and move down layer by layer until you reach the people that do the work. We did the design from the bottom up. We loosely built what people now call the Spotify model. We just called them small, cross-functional teams. We then grouped squads into tribes and tribes into domains. By doing this, we reduced management layers. We would have never gotten to that result going top down — leaders would have protected their empires.

Our philosophy was to get these squads to organically work together so they could connect the dots (dependencies). Over time, companies start adding processes, enterprise architecture groups, project management offices, and strategy groups. I don’t have any of those. When these groups connect the dots, they add cost and time, and they reduce innovation.

— Smith

Smith brought his learnings to his role at World Kinect, where leaders accomplished a comprehensive organization redesign:

-

Get organizational redesign done early (don’t let it drag out).

-

Include more leaders in the redesign process.

-

Develop a measurement system for leaders that mirrors the AMA for teams.

Smith talks about his organizational redesign process at World Kinect, which evolved from earlier disappointments:

This time, I did two things fundamentally differently. First, I included all 55 global executives in my global leadership team in the design of our Agile operating model.

To ensure broad, inclusive, diverse participation, I invited all 55 executives to work with me in Miami in intense design sessions held over a week. Continuing to use the basic Spotify model, we followed the work and designed squads, grouped squads into tribes and then into domains. Every day, we broke up into design teams and shared retrospectives and showcases. At the end of the week, we collectively agreed on our overall design that only required 27 executives and reduced the number of levels from 10 to four. Since all executives participated in a transparent process, there was huge buy-in, even though everyone realized this simplified design was going to impact roughly 50% of the leaders.

Second, we needed to complete an assessment and selection process to assign leaders to the new roles. We completed this process in about three weeks. Overall, the process from the initial design process to assessment, selection, placement, and implementation was one month. This was the most inclusive and fastest organization restructure I had ever been involved in and a huge improvement over my prior experiences.

The leaders who remained were both Agile and technical. Gone are the days when managers at any level, from teams to the C-suite, can prosper without technical competence. Today’s organizational mantra should be, “Your business is technology, no matter your business.” In the era of digital businesses, the entire leader ladder needs to have technical knowledge. Smith certainly does.

Reduce the BMI

Every layer of management increases an organization’s resistance to change. Abernathy came up with the idea of a BMI,4 a ratio of enablers to doers. When every layer of management blurs the communications and alignment between the top and bottom of the organization, action is needed to reduce those layers:

A good BMI ratio is 10% to 12% total enablers to total doers. You have to make hard decisions to flatten layers. I went from multiple levels to four: squad lead, tribe lead, domain lead, and me.

— Smith

Enablers include roles like scrum master, Agile coach, and project manager. Although each enabler role helps product/project teams deliver value, Abernathy is increasingly finding that companies are misdistributing engineering, collaboration, and management talent — usually by undervaluing engineering talent:

At a large client, I had 20-plus coaches coaching the engineering teams, and only one of them had ever written code. The rest had no clue what I was talking about regarding engineering excellence. Yeah, some knew the word DevSecOps, but if you lifted the flap even a little bit, they had no clue. They couldn’t train, they couldn’t coach, and they couldn’t consult at an engineering level.

One of the things I’m working on is finding a way to address what’s happened with the Agile movement. The performance-people pendulum has swung completely to the right. Agile coaches drink the Kool-Aid and rarely talk about performance and accountability. Control is such a bad word that it’s never uttered, which results in a total lack of control in many cases.

One of the most difficult groups to work with are the Agile coaches. Let’s sing kumbaya, we can never be directive even when needed, let’s all collaborate on everything, and we must have consensus before we proceed. This has led to endless discussions and lots of navel gazing. Coaches are expensive, and if they can’t demonstrate value, they are a waste of money.

— Abernathy

This misdistribution problem has recently surfaced in companies as they cut staff. Although most of the cuts are a result of over-hiring during the pandemic, some are using Agile as a reason for their cutbacks. However, a look under the covers often shows they are realigning their talent mix, rather than abandoning Agile.

Convert Traditional Managers to Agile Leaders

One of Smith’s learnings from Suncorp and IBM was that he needed a leader measurement tool like the AMA for teams. He wanted a similar disciplined approach so leaders could learn, practice, measure, and improve their leadership practices:

What we missed was measuring our leaders. We had the AMA for the squads, but we didn’t do a good job measuring who was leading the work. I think we built some good leaders, but we didn’t operationalize that. From what I learned from IBM and World Kinect, we came up with the leadership maturity assessment (LMA) to measure all leaders the same way every quarter and publish it. That got the hearts and minds, not only of the leaders, but of the people doing the work. You’re giving signals to the leader about where they need to get better and where their team needs to get better.

— Smith

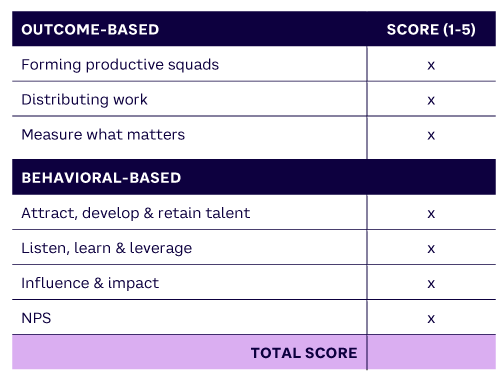

The LMA has seven dimensions (three outcome-based, three behavior-based) and a net promoter score (NPS) — see Table 1.

Outcome dimensions:

-

Forming productive squads. This is probably the most critical dimension. Ensuring squads have the right skills, chemistry, and diversity of thought, gender, and race is critical.

-

Distributing work. This sounds simple, but it might be the dimension leaders struggle with the most. Distributing the right work at the right pace to optimize the productivity of squads is essential.

-

Measure what matters. It is critical to identify the fewest measurable outcomes that give signals to the squads on how they are doing and how to improve. A key tenet is that these measures should be valuable to the squads, not just the leader.

Behavior dimensions:

-

Attract, develop, and retain talent. This is about ensuring your leaders are “magnets” for talent rather than “repellents” and is critical to achieving high talent density.

-

Listen, learn, and leverage. This is the most important dimension. A passionate desire to look outside one’s own frame of reference is a rare trait.

-

Influence and impact. This encompasses finding leaders whose impact/influence is wider than the scope of people they manage. Building leaders whose impact is larger than their remit builds resilience and adaptability in your leadership system.

Smith explains that the final dimension is NPS:

We ask two questions of all employees for NPS: (1) would you recommend your leader to an outside colleague? and (2) would you recommend your squad to an outside colleague? These questions are useful in determining whether leaders are detractors or attractors.

An LMA is critical to giving meaningful, timely feedback to your leaders. We do this every quarter for every leader. We use a rating of one to five for all six outcomes and behavior dimensions, and we add the NPS score to the LMA score.

Smith’s metrics have four distinct properties:

-

They focus on operationalizing an Agile culture.

-

They are qualitative (stoplight) but evidence-based (e.g., the “attract new talent” metric would involve questions about specific hires).

-

They are simple.

-

They are development metrics intended to monitor and identify training needs.

Performance metrics (outcomes, quality, cycle time) are separate.

In addition to reducing layers of middle management, Smith eliminated staff groups such as strategy, project management offices, and architecture groups. Abernathy admitted that:

We made the mistake of cutting the muscle a bit on architects in Suncorp, for which paid a price, and we learned from that. But the project management offices [needed to be cut]. One of the companies I did a transformation for had about 100 developers and 98 project managers!5 I said, “You’ve got to be kidding me.”

They had functional silos of business analysts on this side, developers on that side, testers on this side. People were working on seven projects at once, so of course they needed 98 project managers to coordinate everything.

We got rid of the whole group and reorganized the teams. They reduced their staff by 30% without firing a single person through contract reductions and retirements. I don’t blame the project managers; they were trying to solve a problem. They were the maze runners. The problem was the maze: those silos of analysts, developers, testers, architects, and people working on seven projects at the same time.

Abernathy’s take on this is very interesting. It wasn’t the people in the project management offices that were the problem, it was the functional silos that severely impacted dependencies that project managers were trying to bridge.

The link between setting strategic goals and teams implementing them is middle management. For innovation, creativity, adaptability, and resilience to flourish, organizations must reimagine and reduce those layers.

Smith as a Person

In the final chapter of Wild West to Agile, I offered a challenge to readers:

I don’t just want to know what you think, I want to know who you are. I think the root cause of success is people and their interactions. If this is true, and I believe it is, the better we know each other, the better our interactions can be, and ultimately the more success and well-being we can bring to the world.

So, as I worked on this Update, I wanted to know more about Smith as a person and what it was like working for him. Luckily, Abernathy and Ponton were quite willing to share their experiences:

The troops loved him. Jeff was demanding when he would say, “If you’re not going to be on the Agile train, there’s a number seven bus, and you better hop on.” That may seem harsh, but when transforming an organization, you have to have everybody going the same direction. Another thing I always liked about Jeff was his approachability.

— Ponton

Abernathy adds:

Jeff is such good fun. It’s one of the special things about working with him. Humor is core to his approach. He’s able to laugh at mistakes, laugh at himself, and this attitude energizes people and lifts them up. It’s been a big part of why I work with him. I’ve been Jeff’s sort of right hand through the various transformations he’s led because of the fun and the level of intellectual cognizance he brings. You can learn so much from him while laughing. What more can one ask for!

This is my 42nd year working, and I’ve never met any other C-level executive who has time on their hands to talk and listen to people. He’s the only one whose agenda is not tapped. He has time for people. He’s walking the floor, he’s practicing Gemba, as we call it. He’s talking two, three levels down because of his curiosity. It’s taking people out for a coffee (he loves his coffee!), having a laugh, having a chat. And while doing this, he’s listening intently and sniffing out the key challenges. His biggest skill is problem finding, not problem solving.

Jeff had guts. He had the b…s to speak to power, to speak based on his true belief in this approach. I walked around the transformations with a target on me from day one. But I knew Jeff had my back because other managers would complain to Jeff. They’d say, “Phil is trying to make us do the AMA. Phil wants my managers to go on one day’s training. We don’t have the time for it.” When they complained to Jeff, he would say, “Just do it.” He had the conviction of his belief.

Like Ponton and Abernathy, I found Smith approachable, willing to discuss difficult subjects, and fascinating to listen to, especially his rich career stories.

The Journey Continues

Agile journeys take many forms, and Smith’s is but one of those. Each person, each leader, will have a unique journey. So why is Smith’s journey important? Because he has more than 20 years of successful Agile journeys with three large organizations. He has demonstrated the traits that indicate an effective agile-adaptive leader:

-

An ability to balance between performance (delivering results) and people (maintaining a healthy working environment). Smith focuses on BHAG performance goals. He focuses on talent density at the team level, particularly technical talent, and growing healthy work environments.

-

Someone who seeks adventure, proposing challenging initiatives that are risky but not foolhardy.

Adventurous might be an understatement for Smith. From his decision to move halfway around the world to Australia to become CIO at Telstra to delivering a critical business product while creating distributed Agile at Suncorp, leading risky early conversions to the cloud, and returning to the US to tackle a huge Agile initiative at IBM, Jeff is the definition of an adventurous leader:

-

Someone who can articulate an inspiring vision that engages others in implementing it. His simple, clear, communication about BHAG goals and his curiosity about people at all organizational levels inspires them. That more than 10 senior leaders from Suncorp in Australia followed Smith to World Kinect in Miami is clear evidence of inspiring others.

-

Someone who is adaptive, embracing an envision-explore mindset. Smith is quick to sense, learn, and adjust by looking at reality, whether it conforms to earlier plans or not.

Since it appears that Smith found the “secret sauce” to Agile transitioning and his Agile playbook and maturity metrics are big components of that sauce — why would he share it?

Bobby Knight, head coach at Indiana University for many years, was a tour de force of college basketball. He was revered for his motion offense and wrote a 29-page manual in 1975 that contained winning basketball strategies, complete with diagrams. Why would he share this? The next season, Indiana went 32-0. Other teams might copy Knight’s playbook, but they couldn’t copy Bobby Knight.

To those on an agile-adaptive journey I would caution: you may have Smith’s Agile playbook, but you don’t have Smith. Smith’s leadership and experiences can be invaluable to senior leaders on their journey. But everyone’s agile-adaptive journey begins/ends in different situations and traverses different paths. Learn from Smith, but travel your own road.

Smith’s adventurous journey has now entered a new phase, moving from C-suite positions to membership on several corporate boards and advisor to companies worldwide.

Notes

1 In this second “Voices” Amplify Update, I’ve decided to switch to the word(s) “transforming” or “transforming journey” from the word “transformation.” The word transformation implies an end state, while transforming implies ongoing. Individuals and organizations are always transforming but are never transformed. The word “transforming” can be awkward in a sentence, but it better reflects reality. “Journey,” to me, is an even better word for what transpires.

2 One goal of this Amplify Update series is to learn from executive leaders and incorporate that learning into subsequent articles. In that spirit, the definition of agile-adaptive leadership has been slightly modified in this Update.

3 Smith uses the term “squad” from the Spotify organizational model instead of “team.”

4 For an in-depth discussion of the BMI, see Abernathy’s video.

5 The BMI (ratio of enablers to doers) would be 98/198 = 49.5%. Achieving an acceptable BMI of <15% would reduce the enabler count from 98 to 17.