AMPLIFY VOL. 38, NO. 7

On 28 January 1986, the space shuttle Challenger broke apart just 73 seconds after liftoff, killing all seven crew members. The disaster grounded shuttle flights for three years and led to a profound restructuring at NASA. The Rogers Commission’s investigation found that the explosion was the result of NASA leadership failing to adequately acknowledge and process distributed information about potential O-ring failures in their decision-making — labeling dissenting voices as detractors and deferring to a mindset that if something hasn’t been a problem in the past, it won’t be a problem now.1

NASA significantly overhauled its decision-making processes following the explosion, creating more direct channels to escalate safety issues and establishing the Office of Safety, Reliability, and Quality Assurance (OSMA) to oversee final launch decisions. Unfortunately, the Columbia shuttle disaster in 2003 revealed that the same organizational issues that led to the Challenger disaster had persisted despite these changes, allowing schedule pressures, communication barriers, and risk normalization to continue to drive decision-making.

These tragedies are examples of failures in organizational resilience. We often think of resilience in terms of how organizations respond to unexpected events, but effective resilience also involves the collective ability of an organization to anticipate and avoid such shocks in the first place. Specifically, these examples highlight the propensity for humans to overlook or underweight early signals of potential changes or shocks.2

Two decades later, we can revisit these failures through a new lens. What if NASA integrated machine intelligence to help decision makers better process these emergent signals and take action? In this article, we explore how properly designed human-machine teams (HMTs) can enhance organizational resilience by expanding collective cognitive capacity, countering human biases, and transforming the speed at which organizations recognize and respond to emerging threats.

Why Is Resilience So Challenging?

Resilience is a unique and specific characteristic of systems that happens to be oft-studied of late. It isn’t hard to see why. In the face of accelerating disruption posed by technological forces such as AI and exogenous shocks such as climate change, resilience seems to be the holy grail of organizational strategic capabilities.

The authors of Resilience: Why Things Bounce Back define resilience as “the capacity of a system, enterprise, or a person to maintain its core purpose and integrity in the face of dramatically changed circumstances.”3 If resilience is so important, why do we see so few examples of truly resilient organizations? One reason is the divergence between the scholarly study of resilience and the organizational ability to put theory into practice.

Research on organizational resilience tends to use temporal or phase-based categories. For example, researcher Stephanie Duchek identifies “anticipation, coping, and adaptation.”4 Such categories, although helpful to study resilience, are easier to apply retroactively than in real time. Like a pot of heated water, change tends to unfold slowly — almost imperceptibly — before coming to a boil. If you are the frog in the pot, how do you know where you are in the evolution from emergent signal to shock?

We believe shocks follow a progression from “emergent possibility” to “widely accepted, common knowledge,” with the opportunity to take preventive action lying somewhere in the middle.5 Most approaches deemphasize the anticipatory aspect of resilience because the idea of seeing things before they happen seems daunting, almost mystical. Although there are a variety of disciplines that engage in prediction (from pollsters to prediction markets to forecasters to psychics), there is not a concerted school of science advancing this field of anticipatory resilience specifically (versus responsive resilience more broadly).

Traditional resilience frameworks rely on human solutions to improve anticipation and response. These approaches struggle because they ask humans to overcome the very cognitive limitations that make anticipatory resilience difficult in the first place.

This article explores the notion of anticipatory resilience and looks at how organizations can use AI-powered technologies in conjunction with thoughtful design to increase their resilience. We believe effective anticipatory resilience is based on an organization being better able to (1) acknowledge that an emergent signal of change could have relevant implications for your business and (2) determine when and how to reallocate resources in response.

Human-machine teaming offers a new path whereby machines augment human judgment by processing distributed information at scale, countering biases and accelerating collective sensemaking, while humans provide contextual understanding and strategic accountability.

The Challenge of Anticipatory Resilience

Paul Atreides of Dune, Cassandra of Greek mythology, even Spider-Man … human stories are littered with characters who possess the power of prescience. We’re inherently interested in exerting control over the future. Sadly, this is a very hard thing to do.

Because organizations have traditionally relied only on humans to anticipate the future, they faced steep cognitive and coordination barriers that limit their reliability. Today, AI in the form of large language models (LLMs), anomaly-detection techniques, and powerful prediction engines can serve as active partners in the sensemaking process, helping organizations better recognize and respond to emergent signals of change.

Throughout history, humans have developed technologies to transcend our natural limitations — from writing systems that extended memory to telescopes that expanded visual perception. These represent early forms of human-machine collaboration, albeit with passive tools. When thoughtfully designed, HMTs represent the next step in expanding what's possible in anticipatory resilience.

But first, let’s explore why conventional anticipatory techniques often fall short. There are a host of reasons most organizations are ill-equipped to recognize emergent signals of change. Many employees operate under the (often tacit) assumption that foresight is only the purview of a few people in top leadership (in reality, it requires the whole organization). Furthermore, many organizational decision-making processes are “frankensteined” together around tasks rather than goals, and anticipatory resilience is not a priority goal of most organizations.

Compounding these problems is this: as the pace of tech advance increases, there tends to be an organizational imperative for velocity that impedes organizations’ ability to slow down enough to spot signals or calibrate their responses. Preoccupation with the day-to-day (“We’re too busy just trying to keep the lights on”) tends to breed reluctance to recognize emergent signals and potential disruptions. People only have so much time, attention, and energy, and there tends to be a trade-off between resilience and optimization.

Even well-intentioned humans with enough time, attention, and energy to spot emergent disruptions sometimes fall down on the job. Human heuristics and biases, which help us navigate the world, can undermine our individual and collective abilities to process relevant but counterintuitive information.6

These biases limit our ability to perceive relevant information (e.g., salience, narrow framing, and recency biases), encode it to memory (e.g., availability, conjunction, and anchoring biases), evaluate its relevance (e.g., confirmation, normalcy, and escalation of commitment biases), and process its implications (e.g., groupthink, diffusion of responsibility, and information-sampling biases).

Even when a potential signal is successfully spotted, organizations often mischaracterize its implications. That means enacted responses are not aligned to the real implications of the change, perpetuating legacy business models, processes, and assumptions. Even worse, organizational responses are often delegated to small teams that perform experiments in a closet somewhere with people who do not have the vision and empowerment to navigate and socialize the implications of what they learn. Lastly, when organizational decision makers have already (and perhaps reluctantly) recognized the urgency to change, these approaches can be effective, but the impact is often temporary, with people regressing to old habits and ingrained ways of thinking when that urgency subsides following the shock.

There are many ways for an organization to get it wrong when it comes to anticipatory resilience. Taken together, those shortcomings can be thought of as information-processing problems — areas where collective decision-making processes struggle to effectively absorb, store, or apply information that is not widely held.7 The organizational science literature and many modern business books propose ways to counter the challenges to effective information processing in decision-making, but most focus on human solutions, such as changing cognitions, behaviors, processes, and cultures.

The Promise of HMTs

Advances in AI may offer a solution. Human-machine teaming is an emergent field with the potential to enhance organizations’ ability to overcome the obstacles to effective resilience outlined above. Unfortunately, the true potential for its application is largely misunderstood.

Most organizations approach human-machine teaming in a tactical, tool-centric way, focused on handing off human tasks to machines to reduce costs or speed up processes. This narrow vision can actually undermine an organization’s resilience by promoting flawed legacy processes and reducing individual human accountability. A quick review of AI in the media will show that such juvenile applications of HMT are already the dominant approach.

Inherent in this approach is the tendency to confuse technology implementation with transformation. Engaging in the appearance of transformation without actually transforming can create new challenges or friction points that are difficult to initially spot. This perspective effectively treats machines as replacements for human engagement rather than true partners that can enhance human judgment, creativity, and adaptability.

For example, a recent Harvard Business Review article looked at generative AI use in the workplace and found it often “masquerades as good work” while producing content that “lacks the substance to meaningfully advance a given task.”8 The researchers use the term “workslop” to describe this phenomenon and found that out of 1,150 US-based employees surveyed across industries, 40% reported encountering workslop in the last month.

Such productivity pantomiming often stems from ad hoc adoption — employees integrating AI tools into their workflows without intentional design or organizational guidance. When organizations fail to proactively design HMT systems, they create dual risks. First, there are tactical risks as employees unknowingly persist biases and inefficiencies. Second, there are risks to human agency, morale, willingness to collaborate, and privacy when organizations simply automate tasks without redesigning workflows to elevate human contributions. This compounds problems, leaving employees feeling surveilled, devalued, and disconnected from meaningful work.

We define human-machine teaming as the intentional (re)design of workflows, processes, and interactions in which humans and intelligent machines (including AI agents and advanced robotics) work as partners, each contributing unique and complementary strengths. When it comes to resilience, the promise of HMTs is their ability to transcend the information-processing problem by identifying, connecting, interpreting, and redistributing local knowledge and learning.

Designing HMT for Anticipatory Resilience

Applying human-machine teaming to achieve more effective organizational information processing is no small task. For HMT to effectively deliver value while improving organizational resilience, organizations must invest in a balance that is often not native to them.

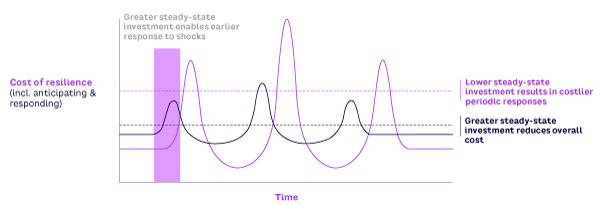

Specifically, organizations tend to underinvest in resilience during periods of stability and overinvest just after disruptions (see Figure 1). Failing to invest in resilience is a temporal trap, committing organizations to a path of accepting future losses for proximal gains. Unsurprisingly, this is happening today with AI: most organizations are not reinvesting the resources unlocked by efficiency improvements into enhancing resilience, preferring instead to send all AI-generated gains directly to the bottom line.

To step up resilience and minimize future losses, a promising avenue for leaders is to invest in, and commit to, building organization-wide HMT systems that effectively increase collective cognitive capacity. This is achieved by leaning into the unique and complementary strengths of both human and machine intelligences, as well as the synergies achievable through their maximal integration, allowing them to achieve outcomes unattainable by either alone.

Humans bring judgment, intuition, broader contextual understanding, and adaptability. Machines bring unparalleled speed, reliability, pattern recognition, precision, and — if designed responsibly — objectivity (i.e., from being intentionally built to minimize bias inherited from humans). Effective teaming, therefore, assigns memory-intensive, computationally heavy, high-tempo, or multifaceted tasks to machines, preserving human cognitive capacity for decisions requiring strategic insight, ethical judgment, nuanced situational awareness, and (ultimately) accountability.

Designing systems like this is akin to risk management workflows that clarify and process relevant, emergent signals in a very noisy environment. The primary difference is that risk management in most organizations is the purview of a small number of humans-in-the-loop, whereas HMT systems designed to process early signals of potential shocks and their implications must promote whole-organization collective accountability.

While most organizations have some narrow layer of their organization dedicated to signal identification, human-machine teaming gives them the opportunity to bring the full depth of their workforce to the challenge of spotting signals.

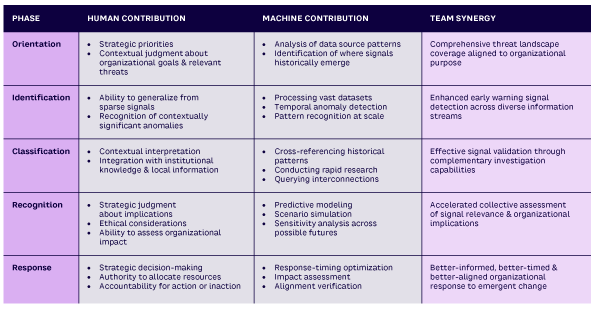

To illustrate how HMTs can help increase anticipatory resilience, we’ve defined five phases of anticipatory resilience where we believe HMTs can be applied for greater effectiveness. These activities are defined with regard to how organizations go about processing potential disruptions: orientation, identification, classification, recognition, and response.

1. Orientation

Perhaps the most critical element in designing resilient HMT systems is determining what direction potential disruptions might come from and where to “listen” for emergent signals of change. For instance, an organization like NASA that’s concerned with preventing catastrophic launch failures should identify where safety concerns surface (e.g., in engineering reports, informal conversations among technicians, dissenting voices in prelaunch meetings, patterns in maintenance records) and design systems to ensure those signals reach decision-makers before things like schedule pressure drown them out.

Identifying and prioritizing the ways such events unfold helps align HMT systems to the goals of the organization and facilitates whole-organization accountability for outcomes, transcending an individual process or task level where accountability is usually assigned. The landscape of potential changes the organization is interested in avoiding (and/or hoping to capitalize on) will determine the data sources on which an AI model will be trained and attenuated. In our NASA example, a model might be trained to monitor indicators of human behavior (e.g., employment records, internal communications) as early indicators of changes that might lead to unsafe practices.

A closely related consideration is how the organization will involve individuals or teams in the expanded HMT. For example, in organizations where everyone touching the work has insight into emergent change, it may make sense for a majority of employees to be involved. These might be companies heavily focused on intellectual property creation (e.g., medical research or hyperscalers) or where small oversights can be incredibly costly (e.g., aerospace or oil extraction). For organizations involved in more conventional production (e.g., hospitality or construction), it may make sense for a smaller number of distributed senior leaders to be primarily accountable while others are more peripherally involved.

2. Identification

Finding emergent signals in the noise can be difficult for humans, primarily because we cannot process the degree of noise necessary to find the signal in it. Our brains either block out noise entirely or use heuristics to categorize the noise, increasing the likelihood that a signal will be missed.

AI excels at this type of processing. It can not only look across a virtually unlimited landscape of diverse datasets instantaneously, but it can also do so across time and explore the interactions between temporal anomalies, allowing it to spot subtle changes that might represent relevant signals of change. AI systems can present those signals to human team members in a prioritized or heat-mapped format to help them focus on what’s most important.

AI systems can also act as “cognitive prosthetics,” helping people and teams circumvent the biases and heuristics that contribute to the information-processing problem. For instance, knowing that groups of people have a tendency to under-sample minority opinions and outlier data, AI systems can intentionally reverse-weight this information, presenting these potential signals back to the group for consideration. Being presented with the information we are most likely to overlook reduces the likelihood that it goes unnoticed.

3. Classification

HMT systems are particularly effective at investigating and validating emergent signals to determine whether they are valid and thus require further attention from the broader organization. Humans bring several unique qualities to the table in helping validate signals. Humans can generalize and abstract to understand signals and patterns in a much broader way, including interpreting the signal in the context of other changes and institutional knowledge that can elude AI. Humans can also integrate what they learn from AI with local information, such as things they hear or knowledge from their own work.

On the machine side, AI-powered tools allow humans to conduct bespoke research in ways not previously possible to help validate the relevance of a signal. This can include using AI to understand where else in the organization similar signals may have emerged, querying interconnections to identify other tangentially related signals, and conducting directed, generative-enabled research.

4. Recognition

Once an individual or team identifies a signal as being worthy of broader consideration, the broader organizational HMT participants can be called into action to conduct independent investigations like those described above, as well as to assess the nature of the change the signal might be heralding and the implications of that change for the organization.

AI makes this exercise significantly more productive than previous technologies or humans alone are capable of. This can include techniques like predictive modeling to understand the potential trajectory a change might take and/or scenario-based experimentation to understand possible futures and sensitivities. Designed and customized by all the people involved in the organization-wide HMT, the AI component can accelerate and coalesce collective assessment of the signal’s relevance to the organization.

5. Response

The collective assessment described above helps ensure that the implications of the potential change are accurately characterized and that the planned response is aligned with the tolerances and goals of the organization. HMT information processing can further enhance the effectiveness of the organizational response by better informing the timing and alignment of investment.

The timing of the response is critical. Too early, and the team risks wasting organizational resources on a ghost hunt. Too late, and it risks missing the opportunity to adapt and succeed. Effective HMT systems can use research and predictive techniques to time the response appropriately.

The level of investment is even more important. As discussed, most organizations don’t want to acknowledge the potential impact of the emergent change. Clearly, the temporal proximity of the change matters, but assessing the potential impact of failed resilience can help organizations evaluate the opportunity cost and right-size the amount of resources deployed in response to disruption.

Finally, HMTs can bring greater clarity to the nature of the change, leveraging the team’s complementary strengths to capture the essence of the potential change and its impact on the organization. A summary of human, machine, and human-machine contributions is shown in Table 1.

Conclusion & Recommendations

In a world where the pace of change outstrips human cognitive capacity to process signals, the most resilient organizations will be those that embed anticipatory capabilities into their fundamental design. We suggest doing this using HMTs because, if designed with clear roles that capitalize on complementarity, they can be more than the sum of their parts: machines can process vast amounts of data and surface weak signals, while humans provide contextual understanding, judgment, strategic oversight, and accountability, among other things.

Organizations tend not to invest in resilience when things are going well. They opt instead to focus on optimization — dooming themselves to a cycle of reactive crisis response. But building anticipatory resilience does not have to be an all-or-nothing activity. Similarly, for organizations that haven’t yet considered such approaches, the best time to embark on this journey is today.

As with any significant organizational change, implementing human-machine teaming requires intentional planning and sustained commitment. The following steps should be considered:

-

Plan. Define what resources and changes are needed, as well as what success looks like across the full range of activities described in the prior section. Establish metrics to measure improvement in signal detection and response speed and assess the potential challenges and risks of implementing human-machine teaming across various domains compared to the status quo.

-

Align. Secure leadership commitment and articulate a clear vision for how human-machine teaming will enhance organizational resilience. This requires buy-in from the top — leaders must understand that this is a strategic capability, not just a technology initiative or a point-in-time exercise.

-

Evangelize. Have senior leaders and managers model the desired behaviors. Celebrate successes early and often, even small ones. If an HMT surfaces overlooked signals or dissenting views that prove valuable, share these examples. Make it clear that spotting and responding to weak signals is high-value work.

-

Incentivize. Go beyond simply sharing success stories and adjust rewards to nudge and reinforce anticipatory behaviors. Recognize employees who identify important signals early. Ensure people have the time and authorization to investigate potential disruptions without penalty. Equally important: remove disincentives for raising concerns or challenging consensus.

-

Enable. Provide necessary resources and training and identify incremental applications of HMT for people to begin experimenting safely. One simple technique to try right away (which we alluded to in the “Identification” section) is to record meetings and use an LLM to distill key points made during the meeting but present them in reverse order of group consensus, effectively highlighting information that was the most easily overlooked.

-

Reinforce and sustain. As you become more comfortable working with HMTs across specific use cases, leadership needs to redouble its commitment and begin to build human-machine teaming into regular workflows rather than treating it as a special project. While doing so, develop and track metrics that reflect your organization’s improving ability to anticipate and respond to emerging threats. Update the system based on what you learn.

That said, it’s easier to outline a plan than it is to execute it. Organizations will have to navigate ethical questions concerning the deployment of machines, confront the risk of human abdication of critical team roles, accept that early experiments may fail, and more.

Critical questions remain. Can organizations implement human-machine teaming through increasing incrementalism, or does anticipatory resilience require full organizational commitment and bold changes to succeed? It’s possible that some partial implementations may prove worse than none at all, creating the illusion of preparedness while preserving the brittleness of existing systems.

Additionally, how should organizations govern systems that blur traditional boundaries between IT infrastructure and human decision-making? When AI surfaces dissenting perspectives or weak signals, who is accountable for acting or choosing not to act? How does an organization determine its optimal investment in anticipatory resilience? In an era of competing pressures for efficiency and growth, is there a sustainable balance between resilience and profitability, or will the most resilient organizations necessarily sacrifice short-term optimization for long-term adaptability?

We don’t claim to have all the answers, but we hope to advance the conversation as the field of human-machine teaming evolves. The goal is not perfection but building up organizational muscle to improve resilience.

References

1 Rogers, W.P., et al. “Report of the Presidential Commission on the Space Shuttle Challenger Accident, Volume 1.” The Presidential Commission on the Space Shuttle Challenger Accident/NASA, 6 June 1986.

2 Vaughan, Diane. The Challenger Launch Decision: Risky Technology, Culture, and Deviance at NASA. University of Chicago Press, 1996.

3 Zolli, Andrew, and Ann Marie Healy. Resilience: Why Things Bounce Back. Free Press, 2012.

4 Duchek, Stephanie. “Organizational Resilience: A Capability-Based Conceptualization.” Business Research, Vol. 13, January 2019.

5 Weick, Karl E. Sensemaking in Organizations. SAGE Publications, Inc., 1995.

6 Tversky, Amos, and Daniel Kahneman. “Judgment Under Uncertainty: Heuristics

and Biases.” Science, Vol. 185, No. 4157, September 1974.

7 Stasser, Garold, and William Titus. “Pooling of Unshared Information in Group Decision Making: Biased Information Sampling During Discussion.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol. 48, No. 6, 1985.

8 Niederhoffer, Kate, et al. “AI-Generated ‘Workslop’ Is Destroying Productivity.”

Harvard Business Review, 22 September 2025.