AMPLIFY VOL. 38, NO. 7

Well-designed force majeure protocols are far more than contractual clauses — they are operational risk management systems. When properly structured, they materially strengthen a supplier’s supply chain resilience across four dimensions: predictability, defensibility, continuity, and speed of response.

Building force majeure protocols that are legally sound, scalable across sites, defensible with contemporaneous evidence, and repeatable across disruptions transforms force majeure from a clause on paper into a proactive resilience system. These protocols reduce disputes, standardize responses across jurisdictions, protect allocation and insurance positions, and create organizational “muscle memory” that accelerates stabilization and recovery. The result is fewer legal exposures, stronger customer trust, and a more resilient and predictable supply chain.

Indeed, in an era of heightened geopolitical tensions, climate volatility, pandemics, and cyber threats, supply chain disruptions are increasingly frequent and complex. In such a volatile environment, companies face increasing legal and operational risks when invoking force majeure clauses, claiming commercial impracticability, or navigating “fair and reasonable” allocation obligations. The absence of scalable, defensible, and repeatable protocols for meeting these obligations can lead to contractual disputes, reputational damage, regulatory scrutiny, and erosion of business relationships.

This article highlights the need for enterprises to adopt formalized response frameworks that are scalable across product lines and geographies, legally defensible under governing law, and operationally repeatable under time-sensitive and stressful conditions. Scalable protocols ensure that companies can apply consistent principles across multiple impacted sites or supply tiers without ad hoc improvisation.

Defensibility is crucial, as claims of force majeure or impracticability and allocation decisions may be challenged by counterparties, litigants, or regulators. This calls for clear documentation, contemporaneous evidence, and alignment with contractual and statutory requirements. Repeatability fosters organizational preparedness and internal alignment, allowing legal, procurement, and operations teams to act swiftly and cohesively using preapproved procedures and decision trees.

Such protocols help companies move from being reactive to proactive and promote good governance and risk management. They also provide a foundation for audits, board-level reporting, and compliance with antitrust and consumer protection laws, especially in highly regulated industries such as energy, automotive, and pharmaceuticals.

Ultimately, embedding scalable, defensible, repeatable response protocols within supply chain governance mitigates legal exposure while reinforcing commercial integrity, preserving customer trust, and enhancing business continuity in uncertain times.

What Is Commercial Impracticability?

Simply put, a commercial impracticability (often colloquially referred to as a force majeure) is an impediment to performance under a contract due to “the occurrence of a contingency the nonoccurrence of which was a basic assumption on which the contract was made or by compliance in good faith with any applicable foreign or domestic governmental regulation or order whether or not it later proves to be invalid.”1

Unless otherwise obligated by contract, where there is a claimed force majeure under contract or where there is a claimed impracticability under the Uniform Commercial Code (UCC) that only partially affects performance, a seller “must allocate production and deliveries among his customers but may at his option include regular customers not then under contract as well as his own requirements for further manufacture. He may so allocate in any manner which is fair and reasonable.”2 “The seller must notify the buyer seasonably that there will be a delay or non-delivery and, when allocation is required …, of the estimated quota thus made available for the buyer.”3

Rising Force Majeure Declarations Across Industries

Between 2022 and 2025, companies reported more than 40 documented force majeure declarations and dozens of related commercial impracticability claims across major industrial sectors, with the energy and petrochemical industries accounting for roughly a third of known events. These were primarily triggered by extreme weather (Winter Storm Uri, refinery flooding, power loss) and infrastructure failures, establishing energy as the most disruption-prone sector.4-6 The global logistics and shipping sector followed, with at least 10 carriers, including Maersk, Hapag-Lloyd, and CMA CGM, invoking force majeure amid Red Sea attacks, Suez diversions, and port closures.7-9

The metals and mining industries saw more than a half-dozen force majeure declarations, often tied to fires, strikes, and landslides, and chemical manufacturers faced multiple outages from feedstock shortages and plant explosions.10-12 Aerospace suppliers encountered policy-driven disruptions from sudden tariffs, and agricultural producers relied on force majeure defenses during record droughts and water scarcity.13,14

The Shift Toward Proactive Force Majeure & Allocations Protocols

Across sectors, these events illustrate a marked shift toward proactive force majeure drafting (with contracts now enumerating climate, conflict, and regulatory risks) and a judicial emphasis on objective impossibility rather than economic difficulty, signaling a new era of predictive and resilience-based supply chain contracting and allocations.

Across these and other industries, force majeure threats are becoming more predictable and contractually codified. “(Un)foreseeability” is narrowing — climate, cyber, and conflict risks are now rather foreseeable. Force majeure and UCC § 2-615 impracticability analyses increasingly hinge on objective physical barriers, not economic hardship. Companies should therefore shift from passive force majeure declarations to prestructured risk-allocation frameworks encompassing force majeure, notice, pricing, allocation, substitution, and other mitigation protocols.

What Does a Force Majeure & Fair & Reasonable Allocations Program Look Like?

Sound Commercial Terms

The purpose of contracts in the supply chain setting is generally to institute governance and mitigate risk, and having sound commercial terms governing impracticability or force majeure, including fair and reasonable allocation protocols (among others), is a must.

This entails being thoughtful across the enterprise to harmonize these terms in contracts governing both inputs and sales and to include terms that satisfy the company’s governance requirements and risk allocation needs/goals. Indeed, parties to a sales contract governed by the UCC typically may vary or “contract out” of the UCC’s default rules.15

Although the obligations of good faith, diligence, reasonableness, and care set forth in the UCC typically may not be disclaimed by agreement, the parties, by agreement, may determine the standards by which the performance of those obligations is to be measured, so long as those standards are not manifestly unreasonable.16

In sum, companies may, and should, take care to develop commercial terms that thoughtfully address which events qualify as a force majeure and the rights and responsibilities of the parties in the event of a force majeure (e.g., terms that address notice, alternative sourcing, allocations, pricing, indemnity, and dispute resolution protocols).

However, sound commercial terms are only a starting point. Companies should ensure these terms are implemented consistently throughout their organizations by also implementing a scalable, defensible, repeatable protocol for responding to impracticability and force majeure, including for making fair and reasonable, and thus defensible, allocations.

Seasonable Notice

Companies should equip employees with the tools and knowledge needed to communicate effectively with suppliers and customers during times of scarcity. The UCC requires companies to provide seasonable notice of any delay or nondelivery, as well as the estimated quota that will be made available to the buyer. Companies may contract as to the meaning of seasonable notice, but force majeure notices must, at a minimum, provide customers with enough information to satisfy the UCC’s duty of good faith and fair dealing. Giving employees templates to use when providing notice is the best practice to consistently meet the seasonable notice requirement.

This would entail working with legal counsel to provide employees with access to and training on predrafted and vetted communication they can easily adapt for each force majeure occurrence. The communication would be crafted to notify customers that the company is invoking the force majeure clause in its contract with the recipient due to a significant, unforeseen event (e.g., a natural disaster, supply chain disruption, or similar occurrence) that has impaired the seller’s ability to fulfill obligations under the agreement.

The communication would also explain that the event and its aftermath have materially limited performance, that the duration of the disruption is uncertain, and that the company is taking active steps to resume normal operations and minimize the impact on the recipient’s business. The letter may include a detailed description of the event, its operational consequences, and any anticipated timelines or updates to follow, including when to expect further communication about any allocations.

The communication would close with an expression of appreciation for the recipient’s understanding and provide contact information for further communication or questions, ensuring continued transparency and cooperation while the force majeure event persists.

Templates should offer enough information to help customers make timely, informed decisions to protect their rights while remaining carefully designed to prevent employees from disclosing excessive details. For example, employees may be prompted by customers who are also competitors to share information that could violate antitrust laws. Employees are also often tempted or prompted to provide information that could be construed as a waiver or modification of the underlying supply agreement between the parties. Companies should create communications templates and protocols that avoid these pitfalls and train employees on how to use and follow them.

Even a carefully crafted force majeure notice, or a communication even suggesting the possibility of a force majeure, may be grounds for relief against a supplier and may trigger customers to demand adequate assurances of performance. Templates can be crafted for these communications as well. Simply put, companies should prepare for this and empower employees to meet the moment by giving them the needed tools.

Fair & Reasonable Allocations

Perhaps the most complex and fraught aspect of impracticability or force majeure arises when companies can meet some, but not all, of their obligations to customers. Even supply contracts that explicitly set forth allocation obligations require fair and reasonable allocations if governed by the UCC.

A major challenge for sellers operating under this requirement is that the determination of what constitutes “fair and reasonable” in any given circumstance calls for a fact-intensive inquiry and may vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction as well as industry to industry. The only statutory guidance is found in Comment 11 to UCC Section 2-615, which states:17

An excused seller must fulfill his contract to the extent which the supervening contingency permits, and if the situation is such that his customers are generally affected, he must take account of all in supplying one. Subsections (a) and (b), therefore explicitly permit in any proration, a fair and reasonable attention to the needs of regular customers who are probably relying on spot orders for supplies. Customers at different stages of the manufacturing process may be fairly treated by including the seller's manufacturing requirements. A fortiori, the seller may also take account of contracts later in date than the one in question. The fact that such spot orders may be closed at an advanced price causes no difficulty, since any allocation which exceeds normal past requirements will not be reasonable. However, good faith requires, when prices have advanced, that the seller exercise real care in making his allocations, and in case of doubt his contract customers should be favored and supplies prorated evenly among them regardless of price. Save for the extra care thus required by changes in the market, this section seeks to leave every reasonable business leeway to the seller.

One may argue that this ostensibly amounts to a business judgment rule, albeit with certain clear caveats.

The first clear caveat is that any allocation “must take account of all [customers] in supplying one.” The second clear caveat is that “good faith requires, when prices have advanced, that the seller exercise real care in making his allocations, and in case of doubt his contract customers should be favored and supplies prorated evenly among them regardless of price.” Accordingly, in making allocations, sellers (1) must consider all customers and (2) cannot engage in sheer price discrimination. Otherwise, sellers are afforded “every reasonable business leeway” (emphasis added). Although this sounds simple, the realities of the supply chain environment add challenges that companies must consider.

The Case for Institutional Protocol & Decision-Making

In any supply chain setting (and particularly where a seller has large numbers of varied customers in multiple industry sectors), the best practice is to develop standard protocols that govern, along with a committee that makes (or at least approves) allocation decisions. It is risky to allow frontline sales and supply chain personnel to allocate ad hoc in times of scarcity.

Imagine, for example, a company with hundreds of customers and sales and supply chain teams organized by sector, all competing for the same scarce product. Those individuals could allow personal monetary incentives or relationships to influence allocations. Even the possibility of those factors creeping in could present customers or courts with the appearance of impropriety (or, at the very least, unreasonableness).

Similarly, imagine procurement employees tempted to offer “expedite fees” or other incentives at a supplier’s request to secure a larger or faster allocation — either to fulfill customer orders or manage allocations. Frontline employees may agree to such demands without fully understanding the potential risks or the company’s rights in these situations.

Leaving aside those risks, allowing ad hoc and individualized allocation decisions creates the risk of inconsistency or bias in decision-making. Certain personnel may believe that one business sector or customer deserves a larger allocation than another — beliefs that may conflict with broader company priorities or legal considerations, creating a risk that the allocation could be deemed unreasonable.

A uniform set of governing protocols — developed and vetted with all relevant factors in mind, including legal requirements, and overseen by an impartial committee — is a best practice for optimizing governance and reducing risk in allocation decisions. At a minimum, having trained frontline sales and supply chain personnel follow consistent protocols is far more effective for governance and risk mitigation than relying on ad hoc, nonuniform decision-making.

Here's a brief real-world example. A company faced a global shortage of a critical input due to a myriad of circumstances impacting several supply sources. This company had pre-vetted force majeure protocols in place that allowed a small group of predetermined key decision makers to trigger the protocols upon receiving force majeure notices from suppliers. This allowed frontline procurement and sales personnel to act promptly, efficiently, and thoughtfully, saving time and resources. It also prevented hundreds of affected (and many disgruntled) customers from having grounds for suit. Each customer was given equal treatment, if not equal allocation, and each customer felt as good as one can feel in such circumstances. This turned what could have been hundreds of threatened suits into a handful of lawyer-to-lawyer resolutions.

The Touchstones of Fair & Reasonable Allocation

Fair and reasonable allocation strikes right at the intersection of contract law and supply chain management. Courts have been fairly consistent across the country and over time in hewing to certain guiding principles. Courts interpreting § 2-615 and its “fair and reasonable” allocation standard tend to emphasize:18

-

Consistency and good faith. The allocation must be based on objective criteria, not favoritism or retaliation.

-

Transparency. Timely, written notice to customers with an explanation of allocation methodology should be provided.

-

No self-dealing. A seller may reserve a portion of output for its own downstream operations only if proportionate and justified.

-

Prior course of dealing. Past allocation practices and commercial norms matter.

Companies that mandate that these principles guide allocation decisions go a long way toward compliance. Of course, this is only the beginning of the process.

Fair & Reasonable Allocation Protocol Components

A hypothetical is helpful to get a sense for how an allocations committee administering allocations protocols might conduct its work. Let’s say a widget manufacturer has 50 customers spread across five industry sectors. A massive explosion crippled the factory that produces a critical input for widget manufacturing, prompting the supplier to declare force majeure. There is no question that the overall widget output is going to be halved by 50%. Companies that apply a thoughtful protocol can more easily meet the moment.

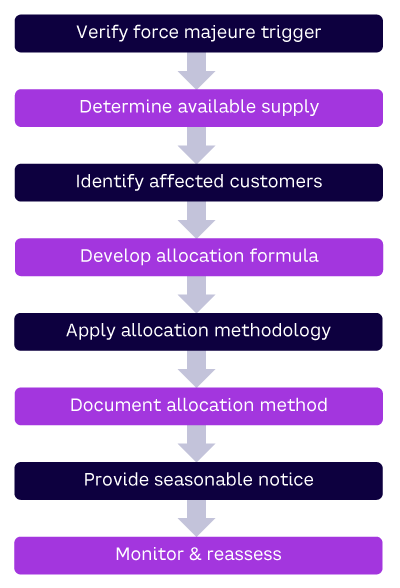

With scalable, defensible, and repeatable force majeure and allocation protocols in place, a response to this scenario may unfold, as shown in Figure 1.

Companies ought to first verify the force majeure trigger. Case law over the years shows that companies should be skeptical when informed that suppliers cannot perform and should confirm that the force majeure event qualifies under relevant contractual language or applicable law.

Assuming it does, companies should determine what portion of capacity is impaired, taking care to document this thoroughly. The next step is determining available supply by calculating reduced production or inventory (the “pool” available for allocation) net of unavoidable operational and safety reserves.

At this point, it is imperative to identify all affected customers by listing every customer contract that is potentially impacted. Companies should understand current orders, open purchase orders, and forecasts and should identify whether, and which, contracts have allocation or force majeure clauses. Companies may wish to identify any key customers (e.g., strategic, regulatory, public contracts).

Once there is an understanding of the pool available for allocation and all impacted customer contracts, an allocation formula should be applied. Companies should be thoughtful in developing the formula with trusted counsel based on all relevant factors. They must choose an objective, transparent basis for allocation, which may include some combination of:

-

Historical allocation, such as using average monthly volume over the past 12 months

-

Pro rata by contract quantity, such as dividing remaining output proportionally among all customers with current purchase commitments (total available ÷ total committed × each contract quantity)

-

Prioritizing essential or safety-related uses (if permitted under law or government direction), such as medical before basic consumer use

-

Tiered allocation, such as combining historical base allocation with some strategic weighting (e.g., long-term partners or government requirements)

Above all, companies should strive to avoid arbitrary decisions and ensure that similarly situated customers are treated consistently.

Finally, but critically, companies should document the methodology contemporaneously, including the criteria used, calculations, internal approvals, and communications. These become crucial if later challenged for breach or bad faith. At this point, companies should provide seasonable notice as discussed above and then monitor and reassess (i.e., update the allocation as circumstances evolve). If capacity improves, the company must readjust or lift the force majeure and restore normal shipments where possible.

Conclusion

A company’s supply chains are its lifeblood. To protect critical assets from crippling liabilities in times of supply chain disruption and scarcity, it is critical to take proactive steps to develop scalable, defensible, and repeatable prestructured risk-allocation frameworks encompassing force majeure, notice, pricing, allocation, substitution, and other mitigation protocols.

In today’s risk environment, force majeure is no longer a boilerplate clause — it is a core resilience discipline. Suppliers that implement legally sound, scalable, defensible, and repeatable force majeure protocols experience fewer disputes, faster recovery, better customer outcomes, and substantially stronger operational stability when disruptions inevitably occur.

Acknowledgment

Mr. Whitlatch would like to thank Steptoe & Johnson PLLC, Meghann Principe, and Kaitlyn Pantelis for their assistance in the preparation of this article.

References

4 MIECO, LLC. v. Pioneer Natural Resources USA, Inc. US Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit. No. 23‑10575, 16 July 2024.

5 “Refinery Halted in Russia’s Flooded Orenburg Region.” Bloomberg, 6 April 2024.

6 “TotalEnergies Declares Styrene Force Majeure at Northern France Site — OPIS.” Market Screener, 11 April 2024.

7 “Shippers Declare Force Majeure as Red Sea Attacks Continue.” Project Cargo Journal, 20 December 2023.

8 Schultz, Hank. “BASF Says Vitamin Production Down Until 2025.” Supply Side Supplement Journal, 22 August 2024.

9 Boswell, Clay. “Europe TDI Surges on Covestro Outage.” Chemical Week, 1-8 September 2025.

10 “Salzgitter Declares Force Majeure on Steel Coil Supply.” Argus, 3 May 2025.

11 “Freeport Declares Force Majeure at Grasberg.” Argus, 24 September 2025.

12 Desai, Pratima, and Clara Denina. “Exclusive: Newmont Declares Force Majeure on Metal Products from Mexico’s Penasquito.” Reuters, 23 June 2023.

13 Hepher, Tim, Joanna Plucinska, and Allison Lampert. “Aerospace Firms Scour Contracts Over Tariffs After Supplier Challenge.” Reuters, 8 April 2025.

14 Jones, Sam. “Cava Firm Freixenet to Furlough 80% of Its Workers in Catalonia Due to Drought.” The Guardian, 23 April 2024.

17 UCC § 2-615, Comment 11 (2025).

18 For example, “Avoidance of the Contract Without Liability, 3a Sales & Bulk Transfers Under the UCC § 14.12” (2024) (citing decades of cases that provide insight into how courts address the issue of allocation).