Listen to any car advertisement on television. What do you hear? "Eco," "green," "hybrid," "zero emissions," and the like. As we see through many media outlets, the focus on going green is at the forefront of most businesses' mindsets. For example, Wal-Mart uses LED lights in its freezer cases and is installing white roofs on its new buildings.1 Newsweek recently published a ranking of the "Greenest Big Companies in America."2 Whether it is about saving money, complying with governmental guidelines and regulations, promoting one's organization or company, or expressing genuine concern for the environment, corporations, nonprofits, academic institutions, and others have begun to identify themselves as "green and sustainable" or as "going green."

Large corporations, which previously have been significant polluters, such as GE and BP, have turned their focus toward the green and sustainability phenomenon, resulting in a considerable improvement in marketplace perception. One key lesson these corporations learned is that thinking and practicing green and being sustainable makes business sense.

It is obvious that more and more enterprises accept the strategic benefits of sustainability. However, not every organization has the same issues or requirements when heading down the path toward sustainability. Manufacturers, healthcare institutions, and the travel industry face many of the more complex issues. Yet "cleaner" industries, such as professional associations, software companies, nonprofits, law offices, and governmental agencies, have different, but just as pressing, concerns about green and sustainability. In between lay retailers, academia, and financial institutions.

Discussions in this space revolve around energy efficiency, greenhouse gases, water use, and management of toxic waste. However, public and private organizations are also beginning to ask some of the following questions:

-

How green and sustainable can a given business operation or process be? What opportunities exist for efficiency improvements or risk elimination so that the business process is green and sustainable?

-

What environmental regulations must an enterprise comply with? Are there any incentives, financial or otherwise, available for compliance?

-

How green can a building or a facility be? What incentives might be available if a building or facility becomes more green and sustainable?

-

Are our procurement and supply chain processes sustainable?

-

How much data or information may be redundant? Will elimination of redundant data reduce storage requirements and provide better efficiency of a data center?

-

What standards exist -- or might be in development -- that allow an organization to measure, monitor, and report on its levels of green and sustainability?

-

How can we monetize our small carbon footprint? Has the carbon credit become a global currency that we can bank? The bottom line is: "Can we cash in on this aspect of our greenness and sustainability?"

Often we find these questions either have no answer or have many answers. The overarching questions are: Once we have identified the motivation for and articulated our vision of sustainability, how do we integrate that vision throughout the enterprise? How do we continually improve our sustainability into the future? Both the questions and answers permeate many aspects of an enterprise, from motivation through business processes, operations, IT applications, and infrastructure. Over the past 10 years, a great deal has been learned about the effectiveness of enterprise architecture (EA) in facilitating the alignment of business visions and processes with operational capabilities. Can the same techniques be used to drive sustainability throughout the organization?

Before we attempt to answer that question, let's make sure we have the same definitions of the basic terms "green" and "sustainable."

DEFINING GREEN AND SUSTAINABLE

Invariably, when one of the authors would say that we were writing a report on taking an architectural approach to green and sustainability practices, the first questions we'd hear would be: "What do you mean by 'green'?"; "What do you mean by 'sustainable'?"; and "If a company is green, is it also sustainable?"

While the increasing awareness and interest in greenness and sustainability are encouraging, the challenge begins with the terminology itself. These two labels are applied frequently and often interchangeably with little understanding of what they truly mean. The terms are heavily loaded with multiple, sometimes conflicting, definitions. Not only do different industries have different needs and different definitions when it comes to these concepts, various parallel standardization efforts around the globe make it even more difficult to use a single vocabulary and rating system. Thus, a major challenge facing this global shift toward sustainability is the lack of clarity when trying to define the basic terms "green" and "sustainable."

Obviously, a common set of terms and definitions would promote guidelines for order. There is a clear need for an international, industry-standardized definition for each term and an articulation as to how these words not only relate to each other but to the businesses that invoke them. As with defining any part of vocabulary, the solution to this problem will take some time. In the meanwhile, we need working definitions to make progress toward sustainability.

The first step in achieving clarity is to recognize that "green" and "sustainable" mean different things. They are distinct terms, and each has its own definition.

What Is Green?

Let's look at a few definitions of a green business from various sources on the Internet. To begin with, we have the definition offered by the Bay Area Green Business Program. The Bay Area Green Business Program was developed by a coalition of county governments in the San Francisco Bay area with the purpose of verifying that businesses, mostly small to medium-sized ones, meet specific standards of environmental performance. It defines green as follows:3

To be a green business, first bring your operations into compliance with all environmental regulations. Then go beyond compliance to meet the general practices and targeted resource conservation and pollution prevention measures which are summarized below.

General Practices:

Track water and energy usage and solid and hazardous waste generation.

Adopt a written environmentally preferable (or green) purchasing policy.

Establish a "green team" that can help guide efforts to green your business.

Provide three on-going incentives or training opportunities to encourage management and employee participation.

Inform your customers about your efforts to meet the Green Business Standards.

Assist at least one other business in learning about the Green Business Program and encourage them to enroll.

This definition is rather tactical in nature. It does contain precise environmental goals and several measurable objectives. But, for our purposes, it lacks a connection to how the business is run.

Another definition of a green business comes from a discussion that took place on the LinkedIn social networking site earlier this year. Justin Knechtel, president of The Knechtel Group, posted this:

A truly green company is one that actually implements a green plan that's harmonious with their strategies/forecasts throughout every facet of their business. It's built into their business model the same way marketing is. Green evolves with their growth and is used as a tool for not only reducing costs, waste, and environmental impact, but simultaneously increasing revenue, brand awareness, efficiency, and employee loyalty.4

The intent is good. This definition has a strategic focus and certainly emphasizes how green programs must be an integral part of the business. But it needs a more precise definition of what a green program is.

What we would like is a definition that blends the ideas from these two offerings. Here are some noteworthy features of a green enterprise that we gleaned from the two examples:

-

Green strategies are congruent with the business's overall strategy and they evolve over time. Green activities are integrated throughout the value chain.

-

The goals of a green strategy include reducing costs, environmental impact, and risks while increasing revenue and stakeholder value.

-

The organization goes beyond compliance with regulations by striving to reduce or eliminate the negative environmental impact of its products, services, policies, and assets.

-

Available resources (water, power, and so on) are consumed in a responsible manner.

-

The business's environmental practices are not limited to internal activities. The business also extends its activities to customers, partners, and like-minded enterprises.

When we combine these key attributes of a green enterprise the following definition evolves:

An environmentally responsible enterprise (green) actively reduces the environmental impact of its products or services, processes, and assets across its entire value chain, congruent with its normal operations, and it has clearly articulated environmental strategies to reduce costs and risks while also increasing stakeholder value.

The obvious next question is: Are "green" and "sustainable" synonymous? The answer is, no, they are not. Nor does meeting the criteria for a green company automatically mean that it is also sustainable. As you will see in the next section, becoming green may not always lead to sustainability.

What Is Sustainability?

If an organization is green, is it also sustainable? Sometimes yes and sometimes no. Traditionally, an enterprise was considered sustainable as long as it was financially viable. There is a growing awareness that environmental and social concerns are also important, which raises the question of whether financial viability should be the sole measure of sustainability.

Based on input from various discussions across industry and standards organizations, we propose the following definition of a sustainable organization:

An enterprise is deemed sustainable if its products, services, policies, and assets are balanced across three dimensions: (1) economic viability; (2) environmental responsibility; and (3) social equitability.

It is the commitment and the ability to address all three dimensions simultaneously that makes an enterprise sustainable. The three aspects of a sustainable organization are not distinct from each other and must be addressed together.

As with many other aspects of a business, there are both internal and external dimensions of sustainability. For many enterprises, sustainability reaches beyond their traditional boundaries into partnerships, supply chains, and customers or clients. If an enterprise looks only at the economic viability of its supply chain, it will miss out on understanding the impact of the supply chain on environmental responsibility (Is the packaging recyclable?) or its social equitability (Are the supplier's factories sufficiently safe for the workers?). Consider the following statement taken from Kodak's Web site about its compliance to the European Union's (EU) Restriction on Hazardous Substances (RoHS) Directive:

Kodak is committed to meeting the requirements of the RoHS Directive and has modified its corporate standards accordingly. However, we also understand that the transition to alternative materials in some applications will pose challenges. These requirements and the associated challenges significantly impact our supplier base. Consequently, Kodak is taking steps to ensure that our suppliers understand our requirements and work with us to ensure that our equipment products conform to our standards and thereby the RoHS legislation. We recognize that our suppliers and other business partners are key allies in helping us achieve our environmental goals.5

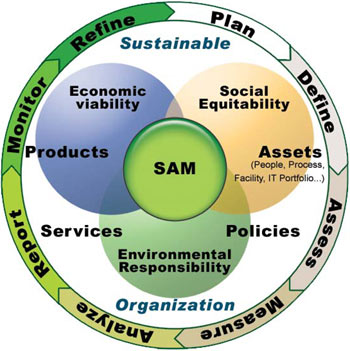

The diagram of a sustainable organization shown in Figure 16 provides a framework for discussing the relationship of the three key dimensions of sustainability. It is quite common for some aspects, such as facilities or processes, to fall into overlapping areas. Also, the balance between the dimensions will differ between organizations and industries.

Figure 1 -- Dimensions of a sustainable organization. (Source: OMG Sustainability Special Interest Group.)

Let's look at the elements of Figure 1 more closely.

Economic Viability

An enterprise can be environmentally responsible and socially equitable only as long as it is economically viable. If it costs an enterprise more to produce its products or services than it can make by selling them, then it will not be economically viable. Without economic viability, an enterprise cannot continue to exist, let alone invest in addressing its environmental or social footprints.

This dimension of the sustainable organization addresses both the tactical and strategic running of the enterprise. It really is no different from what companies are doing today, with the exception that decisions made are balanced against the other dimensions of the sustainable organization. Areas of focus for economic viability include, but are not limited to:

-

Products and services

-

Operations costs

-

Supply chain

-

Distribution

Environmental Responsibility

If a business fits the definition of a green enterprise proposed above, then it is addressing the dimension of environmental responsibility. In an attempt to actively reduce or eliminate its environmental impact, the business may take a hard look at and change how it deals with any of the following, given the constraints of economic viability:

-

Waste management

-

Emissions -- carbon, toxins, water quality

-

Resource usage -- power, water, raw materials

-

Recycle/reuse -- enterprise operations, supply chain, manufacturing

-

Product lifecycle impact -- supply chain, R&D, manufacturing, product use and disposal

As shown by the quote from Kodak's Web site, environmental responsibility has the potential to expand the edges of the enterprise. HP provides us with another example: not only does it monitor and manage its own environmental impact, it is actively involved with the members of its supply chain to reduce their impact, too.7

Social Equitability

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) is of growing interest to many enterprises. Like environmental responsibility, social equitability may permeate the entire business in obvious and not-so-obvious ways. The line between environmental responsibility and social equitability is not always a very clear one. For example, the EU's RoHS Directive sets a maximum concentration of lead and five other hazardous chemicals in an electronic product.8 Lead interferes with the development of the brain and nervous system, especially in children. Is reducing or eliminating lead in products an environmental or social responsibility? The answer to that question is less important than understanding the requirements on your enterprise that arise out of compliance with the regulation.

A small set of social equitability considerations an organization may take into account are:

-

Safety -- products, people, facilities

-

Processes

-

Facility planning -- telecommuting, outsourcing

The appropriate balance between all three of the dimensions or aspects of sustainability will differ between organizations and industries, even within industries. For example, within the healthcare sector, hospitals have significant challenges with disposal of hazardous waste, while insurance companies are more concerned with reducing paper utilization or power consumption in their data centers.

The Sustainable Process

As seen in Figure 1, encircling the dimensions of the sustainable organization are the basic steps for initiating and continually improving a complex process, such as sustainability (plan, define, assess, measure, analyze, report, monitor, and refine). To be the most effective, the overall approach should be iterative and incremental. Start out small and gain experience with introducing sustainable practices before rolling them out on a grand scale or trying to extend them beyond the traditional boundaries of the company.

Another reason for incrementally introducing sustainability throughout the company is to overcome skepticism. Many times, portions of the business only go along grudgingly because they've been told they have to. When this is the case, you don't get another chance to try again, so you have to make the first attempt with them count. You can pick your battles, so to speak, by paying attention to the things that really matter, providing immediate value, and creating demonstrable wins. These successes can be used to show the benefits of the sustainability program and justify continual investment in it.

It is important to keep records, but you also have to actually look at the data collected. Keep track of what you're doing, measure it against goals, and incrementally improve on things. Metrics are one of the best ways to demonstrate the value of both sustainability and architecture.

The Chief Sustainability Officer

Initiating a sustainability program, like any other transformation, requires organizational change. The challenges rest in managing and motivating change, in changing mindsets, and in gaining support. Understanding what the transition to sustainability means for the organization is as important in the overall shift as is the process of how it is done. From EA initiatives, we have learned that an organization needs executive-level support and a dedicated team with both the authority and influence to affect change.

When enterprises, such as SAP, DuPont, Google, and Georgia-Pacific, create the position of chief sustainability officer (CSO), they signal their commitment to implement sustainability throughout the business, especially since the position reports directly to the CEO. The CSO role establishes that someone is clearly responsible for the effectiveness of the program. To succeed, this person will need a dedicated team that helps groups throughout the enterprise understand and adopt sustainability practices. Like enterprise architects, the CSO's sustainability team will need the authority, influence, and expertise to affect changes across the enterprise. To do this, it will need to understand the roles, motivations, and resistances throughout the enterprise.

THE CHALLENGES IN IMPLEMENTING A SUSTAINABILITY PROGRAM

There are numerous challenges, both internal and external, in implementing a sustainability program. This report does not elaborate on methods for increasing the sustainability of your supply chain, reducing power consumption, or the myriad other potential ways to improve your enterprise's green footprint and sustainability. A search of the Internet or Amazon.com on any of these topics will provide an overwhelming number of sources to pursue. In this report, we want to provide you with the tools to thoughtfully incorporate the sustainability requirements throughout the processes, applications, operations, and infrastructure of your business in a consistent, adaptable way.

In order for any business to be successful in its sustainability initiatives, there needs to be an overhaul of the mission and vision statements to include honest language on these terms. Adding "green" and "sustainable" to the statements may be necessary, but the new words alone are not sufficient for a business to become sustainable. More importantly, the organization must incorporate green and sustainability into their processes and practices. Adopting green and sustainable practices can enhance ROI by saving money on resources and by enhancing overall organizational efficiency, as well as by streamlining IT and other workplace technologies. There are a few important things to keep in mind:

-

Everyone's perspective is different. Everyone's understanding of sustainability is different. The level of interest in sustainability varies depending on the stakeholder and the dimension or aspect under consideration. For example, a business analyst in the customer service department has different concerns from a manager in the data center. The former wants fast, fail-safe retrieval of information to ensure the business's financial viability. Yet the latter wants to reduce redundant systems to decrease power consumption for both financial viability and environmental responsibility of the business. Both the analyst and the manager are concerned about sustainability, but their views of what is necessary to sustain are different based on their own perspectives.

-

It is complex and multidimensional. Any enterprise-wide initiative is inherently complex and multidimensional. Initially, it may not be clear how to tease out where individual sustainability requirements apply within the value chain. Metrics vary for different audiences inside and outside of the business. The enterprise operations and infrastructure need to be aligned with the business's sustainability goals and requirements -- something that does not always happen easily or naturally.

-

There is a need for common semantics. The terminology surrounding green and sustainability is currently imprecise and inconsistent. A common set of terms and definitions would reduce confusion across the enterprise and industry. Ideally, an international standard will emerge that defines each term and articulates how these words relate to the businesses that invoke them. But whether or not a set of standards evolves, an enterprise must ensure its own terminology is consistent.

SOUNDS LIKE ENTERPRISE ARCHITECTURE, DOESN'T IT? AN ARCHITECTURAL APPROACH TO SUSTAINABILITY

Do these goals sound familiar?

-

Need for common semantics

-

Alignment of processes, applications, infrastructure, and operations with the business goals and requirements

-

Understanding the current systems and providing a roadmap toward future systems

-

Aggregation and presentation of information to support executive decision making

These are a few of the benefits of enterprise architecture. We know from experience that using an architectural approach to address common vocabulary and define, assess, measure, analyze, report, and monitor different dimensions of an enterprise brings clarity, understanding, and consistency to enterprise initiatives. Let us look at how an architectural approach can facilitate the adoption of sustainability throughout an enterprise.

When first addressing an issue, enterprise architects ask the following questions:

-

Why are we doing it?

-

What are the implications at an enterprise level? What additional benefits are possible?

-

What exactly do we need to do?

-

What does it mean for our organization?

-

How do we make it happen? How do we get there from where we are now?

-

How do we know if it's working?

Of course, anyone can ask these questions. But an architect takes a formal, analytical approach to answering them. The answers to each set of questions can be represented in one (or more) formal models. These models have specific relationships to each other and to an overall process. For example, the output (the specific model) of one step of the process is the input to the next step. And the process and models provide traceability so that specific items (components, processes, policies, etc.) can be traced back to the strategy and goals that they implement, and traced down to the next level of detail about their implementation. In addition, all of this fits within an overall governance, measurement, and reporting framework. Let's take a look at how an architectural approach would be applied to sustainability by asking the above questions.

Why Are We Doing It?

The first step is to understand the motivation and requirements; in other words, why is an organization trying to be sustainable? We can identify several reasons, such as:

-

Cost reduction. There are many different opportunities for reducing costs by adopting a sustainable approach. Some examples are:

-

Reducing the use of resources reduces the costs to acquire them.

-

Reducing the use of resources reduces the costs to dispose of them, which can be substantial depending on the type of waste.

-

Reducing inventory, storage, shipping, and labor.

-

-

Regulatory requirements. Many industries have stringent requirements for the procurement, handling, and disposal of materials. Compliance with these requirements is not only necessary but can bring added benefits. The EU's Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment (WEEE) Directive requires manufacturers of electrical and electronic equipment to assume responsibility for the collection and disposal of the products they manufacture.9 WEEE has become the model for regulation in many non-EU countries, including Canada, China, Mexico, and Japan. To respond to WEEE, manufacturers must add take-back and recycling programs to their processes or risk losing markets where WEEE is in effect. In addition, they are rethinking the design of new products to reduce end-of-life waste in the future. But there are other advantages, too, such as building consumer loyalty as a result of take-back and recycling programs.

-

Incentives. Incentives for sustainability exist in many different areas. A new area called incentive-driven compliance (IDC) is being explored by many businesses to encourage better compliance and innovation. As with any incentive program, governments and other organizations intend to encourage beneficial behavior with financial gains while discouraging undesirable behavior by leveraging penalties. An interesting balance of these two methods exists for Swiss citizens where recycling is free, but each bag of rubbish costs the household money. Incentives for organizations include:

-

10% (US $78 billion) of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act funds are allocated for clean energy, energy efficiency, environmental and green transportation initiatives.

-

The Canadian government announced a CAD $1 billion program to support environmental improvements for the Canadian pulp and paper industry, a sector not normally associated with greenness.10

-

In 2007, the US state of Arkansas created a grant program to assist in the recycling of electronic waste.

-

-

Improvements in efficiency. Many of our existing processes are based on decades-old metaphors and technologies as well as outdated models for the real cost of acquiring and disposing of resources. Often, significant efficiencies and cost reductions may be gained by updating internal and external business processes. We'll illustrate this point later with an example of paper reduction.

-

Environmental/community responsibility. In the San Francisco Bay area, if a company tracks its resource usage and its waste generation, it can be certified by the Bay Area Green Business Program. This gives the business a higher profile in an environmentally sensitive community and may translate into customer and brand loyalty. On a global scale, a good deal of electric and electronic waste is sent to Africa and China. Chemicals in these products, such as lead and cadmium, often end up in the air, water, and soil of the places where the products are disassembled. Take-back and recycling programs aim to decrease and eventually eliminate this source of hazardous waste in less privileged economies.

-

Reputation/leadership. There is an internal and an external component to reputation and leadership. HP's long history of concern for the environment demonstrates both.11 Let's take a step back to the early 1970s when the company:

-

Began an internal program of recycling printouts and punch cards (remember those things?).

-

Created the position of environment control coordinator.

-

Began monitoring its operations to reduce pollution.

-

In the decades since, HP has continued to be a leader in sustainability efforts. But HP is not satisfied with only addressing these issues within the company. It leverages its experience and reputation to help suppliers and others improve along the environmental responsibility dimension.

Having fleshed out the answers to these questions with business and corporate leaders, an architect could use a business motivation model (like the one in Figure 3 discussed later on) to document them.

What Are the Implications at an Enterprise Level? What Additional Benefits Are Possible?

Sustainability does not exist in isolation. We must understand how it fits into an overall enterprise perspective. We do not want to optimize a process or policy for sustainability at the expense of suboptimizing the overall enterprise. So, first, we need to understand how sustainability fits into our enterprise strategy. Is it consistent with the overall strategy? How does it enhance or conflict with specific areas? Are the goals for sustainability consistent with achieving the overall strategy? Do we have to update the strategy and goals to be consistent with our sustainability commitment?

Next, we want to see how we can leverage our efforts toward sustainability across the enterprise. For example, are there additional cost incentives that can be achieved? Could the reduction of paper improve reporting and compliance?

Let's say that to reduce paper we decide to implement online account statements rather than mailing the statements to customers every month (unless they opt to keep getting paper). Obviously, we will save costs on paper, postage, returned mail, and so on. But, what other opportunities does this present? Perhaps it will reduce the load on customer service, since customers will be able to see their accounts in real time themselves. Or, we can customize the billing format for different customers to improve customer satisfaction. We could provide real-time, targeted promotions to specific customers to increase cross-selling. We could provide other self-service options, such as automatic bill payment, profile or account information change, and more.

Given these opportunities, we need to understand which ones support our overall strategic goals and then how we can take advantage of them. What new processes will we need to introduce? What information will we need? What new systems will we need to support them? What new infrastructure will that require? When?

Let's extend this example a little further. Say that to implement online statements will require us to move to an n-tiered application architecture and to introduce new Web and application server tiers. This kind of modular infrastructure is perfect for a virtualized environment. So what are the enterprise plans for virtualization at the data center level? (This is one of the simplest ways an enterprise can reduce power consumption.) Do those plans support the new requirements for e-statements and future growth toward e-billing? Will we be moving to the right kind of systems and capacity, or do we need to reevaluate our virtualization plans?

The important point is that, from an enterprise perspective, an attempt to "simply" reduce paper consumption can have wide-ranging implications.

What Exactly Do We Need to Do?

Now that we understand the motivations, goals, and objectives; have identified a variety of options for achieving them; and have examined them in the context of the overall enterprise, it is time to decide on exactly what actions will be taken.

Here we need to evaluate all of the different options and understand the implications and dependencies. What processes will be changed? What new processes will be introduced? What are the reporting and compliance implications? Exactly what systems and applications will change or be acquired and how? What technology will need to change or be acquired and how? What new policies will need to be put in place? What are the priorities? What are the dependencies? What resources are available to apply to the transition?

Later in the report, the roadmapping example illustrates a technique for taking all these aspects into consideration.

What Does It Mean for Our Organization?

Hopefully, you can see that this is a complex, multidimensional problem. And, like any other transformation, the biggest challenge is likely to be organizational change. How will middle-level management be incented to make those changes, especially if they threaten the status quo? For example, what will happen to the manager and the group of people who do paper billing statements when they are largely replaced by e-statements?

Also, we need to recognize that different parts of the organization will be interested at different levels and in different aspects of sustainability. For example, operations will be interested in reducing power consumption and cooling by server virtualization and other techniques. Development will be concerned with new applications and reduction of redundant systems and storage. HR will be concerned with moving to a corporate intranet and employee portal. Business units will be concerned with process improvement and waste reduction. Procurement will be concerned with buying more ecologically suitable products. Facilities will be concerned with recycling and energy usage in the building. IT will be concerned with more efficient and energy smart equipment. Corporate relations will be concerned with public relations aspects of the enterprise initiative. And so on.

To facilitate organizational change, we need to understand the big picture, the roles that different groups play, and their motivation and resistances. Understanding what the transition to sustainability means for the organization is as important in the overall transition as developing the list of what to do.

How Do We Make It Happen?

With the identification of tactics and organizational issues out of the way, it's finally time to put a roadmap in place to implement the transition. Roadmapping is a standard activity for enterprise architects. First, understand the current "as-is" situation. Next, describe the end game, or "to-be" vision, and perform a gap analysis. Then, prioritize the activities, understand dependencies and what can be done in parallel, account for resources, identify intermediate milestones, and develop a roadmap that ties initiatives to business drivers and identifies the projects, processes, systems, and technology implications. See Figure 5 toward the end of the report for an example of a high-level roadmap.

How Do We Know If It's Working?

After all that, we're still not done. How do we know if it's working? How do we measure progress? What objective information do we have to make midcourse corrections? How do we report the results to leadership?

As part of our business analysis, we should have identified key goals and objectives. These will lead us to a first pass of metrics that we need to collect. One aspect of architecture is the specification and use of standards. So this is a good time to ask ourselves: Are there standards, metrics, or recommended methods of monitoring the progress of sustainability? We will want to take advantage of any industry standards that exist and that will allow us not only to measure our own success in a standard way, but also to compare ourselves against industry benchmarks and other organizations. Later in this report, we discuss the OMG's Sustainability Assessment Model (SAM), which addresses standards for measuring sustainability efforts.

Having identified key performance indicators (KPIs) and metrics, we will need to put processes and systems in place to collect the metrics. For example, if we want to reduce paper consumption, just measuring how much paper the entire company uses probably isn't enough. Instead, we will need to know what the different usages of paper are (mailing, reports, copy machines, employee printing, forms, etc.), have some way of measuring consumption across the different usage categories, implement mechanisms to collect the information, and store the results somewhere, such as a data warehouse of sustainability information.

Finally, we can develop reports and dashboards to present progress and perform real-time and ad hoc analysis as required.

WHERE DOES SUSTAINABILITY FIT IN OUR OVERALL ARCHITECTURE?

Given the questions and answers discussed in the previous sections, let's now take a look at how an architectural approach incorporates sustainable and green perspectives into an enterprise. At this point, our motivation for heading down the sustainability path is clear. We have a roadmap. And we have a good understanding of the requirements for this initiative. Based on previous experience with enterprise architecture, we understand the relationship between enterprise requirements and architectural domains.12 Let's quickly review this process before launching into where sustainability fits into the picture.

Sustainable Architecture

The enterprise architecture is the collection of all other architectures combined to meet specific business requirements and goals at an enterprise scope. It defines relationships between the specific domain architectures and how all of the different architectures relate to each other and contribute to the overall enterprise.

Figure 2 shows an enterprise architecture, labeled "sustainable architecture" in the right-hand column, consisting of six architectural domains. Starting at the top right (at the strategic end) and moving toward the bottom (the operational/tactical end) the domains are: business architecture, information architecture, application architecture, technology architecture, and operational architecture. A sixth discipline, performance architecture, adds accountability and continual improvement to the enterprise and spans all of the domain architectures. The overall EA subsumes these architectures, each of which is driven by a different set of requirements and concerns (shown in the middle column). The sustainability requirements (shown in the left-hand column) add to other enterprise requirements to impact the enterprise architecture. Let's briefly discusses each of these six domains.

Figure 2 -- Applying an architectural approach to sustainability and green.

The business architecture describes the enterprise from a business perspective. It is concerned with what the business is, not how the business systems are implemented. This architecture is influenced by enterprise and business requirements and takes into account core competencies and strategies. The business architecture is essential to identifying the core set of strategies, value chains, processes, services, entities, and governance required to support the enterprise -- and to enable an intelligent, prioritized strategy for implementing and improving initiatives, programs, and projects over time. Sustainability is a major initiative affecting strategies, value chains, process, services, and governance.

The information architecture provides a consistent view into, and context for using, enterprise-wide information across processes and applications. It defines the master data semantics and requirements for the primary business entities and offers a managed information environment for both operational and analytical information. The requirements that influence the information architecture come from the business, information, and enterprise domains. This architecture provides the context for facilitating and enforcing a uniform understanding of terminology (semantics) across applications and lines of business.

While focusing on what must be common across applications to meet enterprise goals, the application architecture describes how to build applications and how to use the technology architecture to achieve enterprise capabilities and consistency. The application architecture also describes the overall set of applications and how they are integrated together. New applications will be required to support sustainability efforts. As well, specific architectural styles and the elimination of redundancy can contribute to the reduction of resources.

The technology architecture describes the infrastructure required to support applications, operations, and reporting requirements. It must satisfy specific requirements for distribution, scalability, reliability, device support, security, and application integration. Power utilization of the infrastructure has been the primary focus of green IT to date and will continue to be an integral part of sustainability efforts.

The most tactical of the architectures is the operational architecture. It is driven by the technical and operational requirements of the enterprise and defines how the infrastructure is operated, managed, and monitored to meet the enterprise qualities of service. Operations must be sustainable and strive to minimize energy consumption as well as contribute to the compliance and reporting of resource utilization and other sustainability efforts.

Finally, all of these architectures, and the overall enterprise, is supported by the performance architecture. This provides a consistent mechanism to define, collect, analyze, and report on metrics (e.g., KPIs at the business level, paper utilization at the application level, server and power utilization at the technology level). Although performance architecture is not one of the traditional EA domains (neither is operations for that matter), it is critical to understanding and managing sustainability, compliance, and incentives.

Sustainability Requirements

Sustainability adds to these typical concerns by introducing many new requirements. For example, regulatory requirements impact multiple aspects of the enterprise. New incentives provide additional motivation for sustainability, but first we must factor regulation, compliance, and incentives into our business models, processes, and reporting. New semantics, information stores, and reporting/analytics will be required, as well as new applications to collect, manage, and distribute the information and reports. Not only will this affect the infrastructure in terms of servers, storage, and networks to support these applications, but the infrastructure itself is a subject of the reporting and a target of resource reduction efforts.

Reductions in resources can have far-ranging effects as we show later with an example that centers on paper reduction. Examining resource utilization will expose opportunities for optimizing outdated business processes, requiring new systems, applications, and infrastructure. Especially at the manufacturing and operations levels there are numerous opportunities for reducing resources. Some efforts when viewed in isolation may not seem interesting or economically viable, but when viewed from an overall enterprise perspective they can provide opportunities to leverage efforts across several initiatives or promote new revenues. For example, one way to reduce paper utilization is to provide employee information online in an employee portal. In a study done in the early 2000s, Bank of America calculated that it saved 100 tons of paper annually simply by putting its employee phone directory online.13 Then it was able to leverage the portal for other areas such as online expense reporting.

The flip side of utilization is waste disposal. Any resource that is consumed has a disposal perspective as well. For example, we have to either store or dispose of every piece of paper we consume. And, paper is pretty benign compared to the disposal of manufacturing wastes. Even waste disposal has implications at the business architecture level in defining enterprise policies and practices. Changes in processes naturally trickle down into applications, infrastructure, and operations.

There are many requirements and opportunities in managing the supply chain and in procuring resources. Building on our paper reduction example again, we can reduce resources by procuring lighter weight paper, and we can reduce our environmental impact by procuring paper with certain manufacturing attributes and content. At the business architecture level, we may want to articulate these activities in terms of our stewardship goals and then define policies to specify them. We also need to implement governance processes to enforce them and possibly some new applications to enable, manage, and monitor them.

The low-hanging fruit in green IT is power consumption at the data center through virtualization and other techniques. Even this has an enterprise perspective. We need to have the right kinds of servers and application architecture to take maximum advantage of virtualization. But beyond that, we can reduce application and storage demand by eliminating redundant systems and data.

In other words, requirements for sustainability, like any major business transformation, have far-reaching implications across the enterprise. To effectively introduce and implement them, we need to take an enterprise approach that evaluates all of the potential tactics and addresses them together at an enterprise scope across of all the architectural domains.

RESOURCE REDUCTION EXAMPLE: PAPER

Let's look at an example of applying EA to a sustainability issue at a fictitious financial services company. The reduction of paper consumption is something that all organizations are wrestling with to one degree or another. As we said earlier, the first thing we want to do is understand why we are trying to reduce paper. In our example, there are several reasons:

-

Environmental consciousness

-

Reputation

-

Cost reduction

-

Less paper

-

Less ink

-

Less storage

-

-

Less waste

-

Efficiency improvements

Business Motivation Model

Now the question is, as architects, how do we capture this information and make it useful? One way is through a business motivation model (BMM).14

Figure 3 shows an extract of a BMM that addresses the paper-reduction scenario. The main concepts of the model are discussed below.

First is the vision: to be a sustainable enterprise that is environmentally, socially, and fiscally responsible. To accomplish that vision, we need a strategy. The strategy is: to modernize processes to reduce utilization of resources, specifically paper.

While it's great to have a vision and strategy, we need to have specific goals in order to accomplish the vision and strategy. In other words, the goals amplify the vision, and the strategy supports the goals. Still, the goals are not enough of a target. Thus, we quantify the goals with specific objectives. For our example, one goal and a corresponding objective are:

-

Goal -- to reduce resource consumption and waste

-

Objective -- to reduce paper utilization by 25% by 2012

While there are many goals and objectives, for clarity and simplicity we are including only one of each type of model element in the example. Now the question is how we will reduce paper utilization. In order to achieve that objective, we need to have some specific tactics. One such tactic is: to implement online account statements.

So one way we will reduce paper is to make account statement information available online rather than on paper -- easier said than done. How will we get customers to change? We can inform this tactic in terms of specific policies, such as: to provide incentives to customers to encourage switching to online billing.

While this is all well and good, again, it's not really specific enough. We need some rules to carry out the policies and to enforce the tactics. One rule is: to offer a one-time rebate per account to each customer for signing up for online account statements.

To summarize, the vision of sustainable responsibility is amplified by the goal of reducing resource consumption, and the goal is quantified by the objective of reducing paper usage 25% over three years. The goal is supported by the strategy of modernizing processes. The objective is achieved by the tactic of implementing online account statements. The strategy and tactics are governed by the policy of incenting customers, which is enforced by the rule of providing a rebate.

Finally, the future business service "AcctStatement" realizes the tactic, providing traceability from the IT service to the tactic that it implements, to the objective that the tactic achieves, all the way up to the business goal and strategy.

Tactics for Reducing Paper Consumption

In the BMM, we only showed one tactic, but there are many that we will want to evaluate for reducing paper consumption.15 For example:

-

Duplexing. This includes printing/copying on both sides of paper. This simple action can greatly reduce paper utilization. To implement this, we need to:

-

Implement Managed Print Services to automatically specify duplex printing and provide overall printer device management and reporting.

-

Update printers and copiers with efficient, duplex models.

-

Remove individual desktop printers for most employees.

-

-

Cleaning mailing lists. Removing unnecessary names and duplicates from mailing lists will reduce the amount of mail that has to be printed and sent. A cleaner mailing list has the added benefit of reducing postage. There are several reasons for unnecessary names on mailing lists (former customer or employee, recipient has moved, recipients have multiple accounts, etc.).

-

Reducing paper weight and purchasing specific paper. If we go to lighter paper, we will consume fewer resources for the same number of pages. Also, we can specify paper that has a specific content of recycled and other materials that lessen the impact of the manufacturing of the paper itself. In order to accomplish this, we need to create specific policies, such as:

-

Centralize the purchasing of paper.

-

Enforce paper requirements.

-

-

Evaluating internal report distribution. Thousands of internal reports are printed, distributed, and thrown out every day. There are several things that can be done to reduce paper utilization for internal report, such as:

-

Make reports available online instead of on paper.

-

Clean and reduce distribution lists to those who absolutely require a printed copy.

-

-

Implementing an internal intranet. This leads to an obvious conclusion. We can greatly reduce internal paper consumption by moving our internal communications online instead of on paper. To do this, we will need to:

-

Implement an employee portal (B2E).

-

Implement a document management system.

-

Create policies and governance.

-

Move internal communications to the portal, such as HR, communications, expense reporting, and purchasing requests.

-

-

Putting forms online. Another related activity is to put business (and other) forms online. Not only does this make the most recent version of the form available to those who need it, wherever they are, but it reduces waste in disposing of outdated forms after they have been updated. This tactic can apply to both internal and external users.

-

Providing electronic account statements. The enterprise in our example is a financial services company. It sends out tens of thousands of account statements every month. A significant reduction in paper can be achieved by providing electronic statements to customers instead. This includes the following:

-

Online. Provide a secure way to view accounts online. The next steps are to incent customers to adopt e-statements and provide an opt-out for customers who can't or don't want to receive e-statements.

-

Consolidate. Many customers have multiple accounts. Savings can be had by sending only one combined statement per household, rather than multiple individual statements.

-

Customer relationship and marketing. Once the customers are online, we have the opportunity to provide customized statements and to target specific marketing campaigns to them. This will require new applications for targeted promotions; new marketing systems; new sales tracking systems; and a common, consistent product catalog.

-

-

Offering online billing. Once statements are available online, the next logical step is to provide billing online. This may take a bit more doing, including:

-

Implementing new processes and systems for billing and payments.

-

Validating regulatory compliance.

-

-

Improving internal processes. There are also many opportunities for improving internal processes and replacing outdated paper-based workflows with new, more efficient processes. For example, with our financial services company, we want to improve:

-

Loan origination. Improving the loan origination process will require us to redesign the overall process; create new systems to collect data; implement business process management (BPM) or workflow systems for the new process; acquire new applications and technology to manage document and image storage and retrieval; implement new compliance and reporting systems; implement a migration and rollout plan; and provide training.

-

File maintenance. After loan origination, we can turn our attention to the file maintenance processes.

-

Measuring Progress

One of the important questions that we asked earlier was how do we know if it's working? This can't just be an afterthought but has to be integrated into the overall approach. That is why we emphasized the performance architecture earlier in our discussion of EA.

First, we need to know what our paper utilization is today in terms of how much and for what purposes (mailing, reports, copy machines, employee printing, forms, etc.). Then, we need to measure the change in utilization as a result of specific polices and tactics. Next, we need to report on both our utilization and progress. Finally, we need to support ad hoc analysis of information to look for trends, relationships, optimizations, and so on.

To accomplish this, we will need:

-

A system to monitor paper utilization

-

Data warehouse or other storage of utilization information over time

-

Reporting and analytic systems to consume the data

-

Executive dashboards to present the data

But the reporting and analysis of paper utilization can't be done in isolation. This has to be done in the context of our overall sustainability efforts. This leads us to another important architectural approach.

Putting Things into an Enterprise Context

We are undoubtedly doing many other things to improve efficiency, control costs, increase sales, and be more sustainable. One of the major tenets of EA is to understand the enterprise context and to leverage information, processes, and systems for multiple purposes. This is not simply to facilitate reuse but also to reduce complexity and, more importantly, to eliminate redundant and inconsistent data and processing. In itself, this is a green activity because it reduces the amount of power, servers, and storage necessary for the overall enterprise.

Let's examine our paper-reduction example and see how it looks from a broader perspective:

-

Internal B2E portal. Efforts to reduce paper by putting internal communications and systems online need to be coordinated with the groups that provide that information or service. Information repositories and management systems will need to be put in place and should be evaluated for being shared across organizations. For example, the same document management system can be used by HR and corporate communications. Furthermore, new applications to put expense reporting and purchase ordering online will have to be integrated with existing systems, such as enterprise resource planning (ERP).

-

External B2C e-commerce portal. Using e-statements is really just the beginning of what's possible. In the future, the portal can increase customer satisfaction, improve cross-selling, and provide self-service capabilities to reduce call center demand. To take advantage of some or all of these opportunities requires an enterprise approach. Effective marketing to the customer requires that there be a common customer view. If this doesn't exist, it needs to be put in place. Evaluating profiles and suggesting targeted product promotions requires a common product catalog. If this doesn't exist, it needs to be created. If it does exist, it needs to be integrated with the marketing and other e-commerce applications. Allowing customers to opt out of paper processes provides an opportunity to optimize mailing lists. With just a little bit of thought, the same solution can be applied to internal lists as well.

-

Monitoring, analysis, and reporting. A single system for reporting on sustainability efforts should be implemented. This will need to include paper usage as well as many other aspects, such as power utilization, waste, supply chain, facilities, compliance, and incentives. The overall data collection and storage, analysis, reporting, and executive dashboard mechanism should be designed to span the entire problem space and be consistent with other executive decision support approaches.

-

Virtualization. The organization is planning to adopt virtualization as a way to reduce data center cooling and power requirements. The new systems that will result from many of the tactics for reducing paper consumption need to be coordinated with server and storage virtualization. We need to make sure that the capacity and types of servers and storage needed to support these new systems are consistent with the virtualization plans.

Making It Happen

So we know what we're doing and why as expressed by our motivation and tactics. We've looked at it from an enterprise perspective to maximize leverage and opportunity, and we've got plans for how to monitor and report on everything. Now, how do we make it happen?

The typical architecture approach is to define the to-be architecture vision, understand the as-is scenario, analyze the gap, and create a roadmap to get there from here. We prefer to use a conceptual architecture to describe the to-be architectural vision, as seen in Figure 4.

The diagram shows the internal systems and users on the left -- customer relationship management (CRM), executive dashboard, B2E portal, ERP system -- and external users -- B2C e-commerce portal, call center -- on the right. The area in between shows the systems and functions that will work together to support the overall goals of paper reduction at an enterprise scope. These systems are roughly divided into three areas, noted by the dotted lines. The first section on the left includes the systems that will support the internal (B2E) portal, such as online expense reporting, internal communications, and so on. On the right are systems that will support the external e-commerce applications, such as marketing promotions, self-service problem tracking, e-billing, and so on. In the center are systems that support both internal and external users, such as document management, online forms, tracking, and reporting. At the bottom are some of the major technologies that will be required to support these new systems.

Next, we need to factor all of this into an overall roadmap. I like to use the roadmapping technique developed by Cutter Fellow Ken Orr and Cutter Senior Consultant Mitch Ummel in the Business Enterprise Architecture Modeling (BEAM) methodology. A high-level view of the roadmap for paper reduction is shown in Figure 5.

On the left of the diagram are the main business drivers: cost reduction, increased efficiency, stewardship, reduction of power. Then, the roadmap is divided into four main areas. The very top portion is business process improvement (business architecture). Within this, we show major initiative areas, such as stewardship, internal communications, e-commerce, and process optimization. The middle section shows major applications (application architecture), again, divided into the major areas of internal (including B2E portal, tracking/compliance, online expense reporting, and executive dashboards) and e-commerce (including e-statements, e-billing, and marketing), which, incidentally, correspond to the colors on the conceptual architecture in Figure 4. Below that are the major information-related initiatives (information architecture), such as the data warehouse. Finally, the bottom section shows the technology that will be required to support the tactics and business processes across all of these areas.

Full size, the roadmap is at least 16x24 inches, so we can't effectively reproduce it in the format of this report. Instead, Figure 5 shows an overview. Figure 6 shows a small slice of the detailed business, application, and information portions for 2011-2012.

Figure 6 -- Application slice from architecture roadmap.

Now the detail begins to emerge. For example, in 2011, the business process focus is on process improvement for internal communications. In order to support these processes, a variety of application projects need to take place, including the B2E portal itself and an application for supporting the publication of internal communications on the portal. There is also a business process focus on reporting and compliance. To support these, a paper-tracking system is being implemented, as is the beginning of an executive dashboard. In order to support these activities, a data warehouse initiative is underway. As you can see, some projects span multiple years, and many different activities overlap.

As seen in Figure 6, for 2012, for example, there is business process activities around e-billing and common customer information. To support these, portal, online statements, and online billing projects are identified within the e-commerce thread. Common customer master data is initiated in the information thread. Note that although this won't go operational until 2013, because of the amount of effort involved, it will be started in 2011 to be ready in time.

At the right side of the roadmap in Figure 5 are the outcomes that should be achieved by 2014. Given the underlying performance architecture, the emphasis on reporting and dashboards, the architectural approach, the business planning, and the linkage between systems, tactics, and goals, we should have a pretty good chance of achieving them. But, we have one more step to go through: vetting the roadmap.

What we like to do at this stage is have a review session with the overall team, including program management, business, process, policy, development, operations, and so on -- all stakeholders affected by the plan. At the outset, we know that the first version of the roadmap is not complete or correct, that we have missed items and dependencies and probably included things that don't necessarily belong. But, having put a lot of work and thought into it, it is a good platform from which to start the discussion, and it is a format that is clear. A clear but wrong picture is easy to correct. If the team members can understand it, they will tell you where there are problems. There are several ways to do this, such as projecting the roadmap on a whiteboard, walking through what it means and all the different items, and then drawing corrections to the roadmap on the whiteboard. Finally, after one or two iterations of this, overall agreement is reached.

The last step is to print the roadmap in as large a format as possible, say 3x5 feet, and post it up on a wall in some common area. People will come by, look at it, discuss it, and hopefully, mark it up with corrections as they occur to them. This keeps the vision out in front of the team, keeps people involved, and keeps the roadmap up to date. Although surprisingly simple, it is very effective.

SUSTAINABILITY ASSESSMENT MODEL

The questions and concepts presented in this report highlight the need for both government and nongovernment organizations to step up and create a common standard for defining, measuring, and analyzing an organization's sustainability efforts.

The OMG has embarked on an international effort to develop a technology and domain-agnostic model that will help organizations assess their current and future state of sustainability. This future standard, called the Sustainability Assessment Model (SAM), will provide a vocabulary and a data model to help organizations define, measure, analyze, monitor, and report on their green and sustainability initiatives.16 SAM is proposing the following deliverables:

-

Vocabulary of green and sustainability terms, as well as valid semantic variations where applicable (synonyms, geographical variations, etc.).

-

A Conceptual Data Model representing green and sustainability concepts. This model will facilitate consistent understanding across the business and IT communities.

-

A Dimensional Data Model derived from the Conceptual Data Model to support reporting and analytics. This model will allow organizations to leverage any existing rating standards and to extend their own measurement categories and dimensions.

-

XML Metadata Interchange (XMI) representation of the above models and vocabulary to facilitate interchange of metadata across data management tools.

Scalability of this model will be critical but equally important is the flexibility of SAM to address variability in organizational structure, size, core processes, and commodities.

Let's return to Figure 1 for a moment and consider where the Sustainability Assessment Model fits into the picture. Figure 7 shows the inclusion of SAM.

Figure 7 -- OMG's Sustainability Assessment Model.

Vendors will be able to develop tools to help standardize reporting, develop dashboards, and perform predictive analytics on different dimensions/perspectives of green and sustainability. Public- and private-sector end users of SAM-compliant tools will be able to exchange information across disparate technologies using a standard format. SAM will leverage existing green and sustainable standards/ratings where applicable and available. Therefore, SAM is aimed to be complementary, not competitive, with standards already developed in this area. An important distinction is that using the OMG's model-driven approach, users will be able to extend the model as needed and provide traceability across the standards as well as vocabularies.

In addition to SAM, the OMG Sustainability Special Interest Group is also developing a global, Web-based knowledge base of green and sustainability specifications. This knowledge base will allow anyone to search and discover what standards are available or in development, their lifecycle status, categorization into industries/sectors, and ability to propose and vote on what standards should be developed.

CONCLUSIONS

There is no denying the hype and chaos surrounding the concepts of green and sustainability. Even so, many companies are managing to see through the confusion and discover the strategic benefits of practicing environmental responsibility and sustainability. When they pay attention at the enterprise level to their effect on the environment and their social actions, they have realized lowered costs, fewer risks, increased revenue, and reputations for leadership. How did they accomplish this? Not easily. Enterprise-wide transformations are difficult. They require a long-term view of the big picture, patience, and commitment.

To attain the most benefits, businesses must recognize that sustainability requires an enterprise-wide approach. Sure, they can see lower power consumption in a data center here or less waste generated by paper reduction there. As we have seen time and again, an ad hoc approach to anything is difficult to scale, manage, repeat, or improve upon. Companies understand that they need to initiate and manage sustainability programs across the entire enterprise, but they struggle with how to do so.

Using an architectural approach to drive sustainability makes a lot of sense because many of the key practices necessary for an enterprise-wide effort are already in place in successful organizations. Sustainability initiatives have many of the same characteristics as EA initiatives. They cross domain boundaries. They are complex and multidimensional. They require alignment of processes, applications, infrastructure, and operations. And sustainability requires a robust and adaptable IT infrastructure -- something that is near and dear to the enterprise architect.

The first problem with using an architectural approach for green or sustainability programs is that terms "green" and "sustainability" are imprecise. Until we cut through the hyperbole and multiple meanings and tease out our own unambiguous definitions for these words, we cannot assume that everyone means the same things when using them.

A common and precise vocabulary mitigates misunderstandings, which improves communication across the organization on the topic. So let's clarify our terms. While "green" and "environmental responsibility" are synonyms, "green" and "sustainability" are not. Environmental responsibility is one of three dimensions of sustainability. The other two are economic viability and social equitability. A company can claim it has a successful sustainability program when it is committed to and balanced across all three dimensions.

Once executive-level commitment to sustainability and a common language is in place, the organization is ready to kick off its sustainability efforts. An architectural approach for the initiative begins with understanding the business motivation for the initiative and translating the motivation into strategies, objectives, tactics, policies, and rules. The next step is to understand how the newly articulated goals, tactics, rules, and so on, fit in the overall enterprise. This is one place that an architect's big-picture view provides value. If the goal of "reduce paper" is left up to the individual business units or departments, without coordination between them, the solutions will be diverse, redundant, and difficult to manage and monitor.

Part of understanding how the initiatives fit into the enterprise is to understand what the enterprise's current sustainability efforts look like: the as-is picture of the business. From there, a future vision, or to-be view, of sustainability can be created. The gap between these two is bridged with a roadmap. The roadmap shows what needs to be done, priorities, timing, and the relationships between the pieces.

Making a sustainability initiative happen requires an iterative and incremental approach. This allows for gaining experience (skills development), making quick adjustments when necessary (agility), and providing measurable benefits early and often (credibility).

Progress is measured throughout the process. Before an enterprise begins a sustainability initiative, it needs to know what its starting point is. Otherwise, it cannot determine if the effort is actually an improvement or not. Constant evaluation of metrics provides quick feedback on how well goals are being met and a basis for incremental improvements; after all, smaller changes in direction are much easier to manage than big shifts in tactics.

This report started with a question: can we truly incorporate greenness throughout our business in a systematic way or will it be an ad hoc approach? We believe that enterprise architecture, by facilitating alignment of the business visions and processes with operational capabilities, can lead the way to real sustainability in an organization.

ENDNOTES

1 "Sustainable Buildings." Wal-Mart (http://walmartstores.com/Sustainability/9124.aspx).

2 McGinn, Daniel. "The Greenest Big Companies in America." Newsweek, 21 September 2009 (www.newsweek.com/id/215577).

3 "Green Business Standards." Bay Area Green Business Program (www.greenbiz.ca.gov/BGStandards.html).

4 Knechtel, Justin. "What Is Your Definition of a Go-Green Company?" LinkedIn, 2009 (www.linkedin.com/answers/management/corporate-governance/MGM_CGV/393361-22741922?browseCategory=MGM).

5 "EU RoHS Directive." Kodak (www.kodak.com/eknec/PageQuerier.jhtml?pq-path=7146&pq-locale=en_US&_requestid=6244).

6OMG Sustainability Special Interest Group (www.omgwiki.org/SAM/doku.php).

7 Velte, Toby, Anthony Velte, and Robert Elsenpeter. Green IT: Reduce Your Information System's Environmental Impact While Adding to the Bottom Line. McGraw-Hill, 2008.

8 "The RoHS Regulation." RoHS (www.rohs.eu/english/index.html).

9 "Recast of the WEEE and RoHS Directives Proposed in 2008." European Commission (http://ec.europa.eu/environment/waste/weee/index_en.htm).

10 "Government of Canada Announces $1 Billion to Support Environmental Improvements for Pulp and Paper Industry." Natural Resources Canada, 17 June 2009 (www.nrcan-rncan.gc.ca/media/newcom/2009/200961-eng.php).

11 Velte, Velte, and Elsenpeter. See 7.

12 Rosen, Michael. "Enterprise Architecture by Example." Cutter Consortium Enterprise Architecture Executive Report, Vol. 11, No. 5, 2008.

13 Bank of America Environmental Progress Report, 1997.

14 For more information on the business motivation model, see Rosen, Michael. "The Business Motivation Model: Matching the Means to the Ends." Cutter IT Journal, Vol. 21, No. 3, 2008.

15 Sarantis, Heather. "Business Guide to Paper Reduction." ForestEthics, 2002.

16 OMG. See 6.