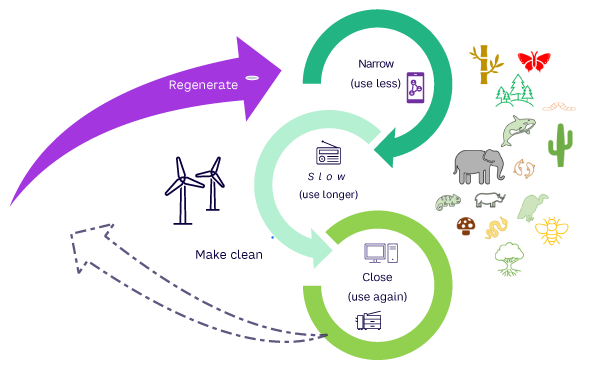

Circular economy (CE) has recently been promoted as an alternative economic model that supports national and regional agendas for recovery, renewal, resilience, inclusiveness, equality, and sustainability in a post-pandemic world. Its principles include designing out waste and pollution, keeping high-value products and materials in use, and regenerating natural systems (see Figure 1).

Strategies for circularity include:

-

Narrowing resource loops by reducing resource intensity and optimizing resources. For example, the smartphone replaced cameras, phones, calculators, game consoles, and even computers.

-

Slowing resource loops through prolonging and intensifying product use. For example, products like computers and electronic appliances could be designed to be more durable for longer use.

-

Closing resource loops by replacing virgin materials with reuse, recycling, remanufacturing, and resource cascading. For example, computer and copier components could be reused within modular systems.

-

Regenerating/restoring resources by preserving and enhancing natural capital. Renewable energy systems are a good example.

Adoption of the CE model has been slow, but changing norms, increasing knowledge, and new incentives and financing are starting to drive CE-related implementations across major industries and large, influential companies. These organizations are mostly headquartered in the more economically developed regions of the world.

Various communities of practice worry that this transition to a broader circular economy is taking place too quickly, that governments and organizations may be so enthusiastic that they are not paying enough attention to the unintended consequences of CE actions. Indeed, history is littered with policies and strategies that had unintended consequences. Sometimes these responses have led to even more difficult-to-tackle problems; local and regional air pollution is a well-documented example.

We (and other voices) have aired concerns about wider environmental and social sustainability factors being neglected in CE-related thinking. A crucial blind spot relates to biodiversity.

Biodiversity refers to the variety and abundance of life on Earth; it includes genetic diversity within species, diversity between species, and diversity of ecosystems. The December 2022 United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity (COP 15) drew attention to the need for urgent action, without which “there will be a further acceleration in the global rate of species extinction, which is already at least tens to hundreds of times higher than it has averaged over the past 10 million years.”

The resulting Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework includes targets to conserve and restore biodiversity. It commits to protect at least 30% of the Earth’s lands, inland waters, coastal areas, and oceans by 2030. It is a significant call to arms around conservation efforts, one that has been recognized and endorsed by scientific communities such as the Half-Earth project, which is dedicated to the protection of biodiversity.

Progress toward biodiversity targets is inextricably linked to changes in consumption and production. Through their global value chains, the negative biodiversity impact of multinational corporation operations extends far and wide across these systems. The World Bank estimates that 90% of total biodiversity loss can be associated with the management of resources within consumption and production systems.

This begs the question: could strategies based on CE-related thinking support the goals of the Global Biodiversity Framework? The short answer is yes. However, we can neither assume that CE-related actions will not hinder biodiversity goals (or other environmental or social goals) nor expect that integrating biodiversity into company strategies and operations will be simple.

[For more from the authors on this topic, see: “The Circular Economy’s Role in Biodiversity Protection.”]