CUTTER BUSINESS TECHNOLOGY JOURNAL VOL. 31, NO. 7

This article focuses on business architecture and discusses how it can be leveraged as an enabler along the strategy realization path to harmonize the execution of business direction across organizational boundaries and initiatives.

Organizations struggle with realizing business strategies, particularly when those strategies cross business unit, product, and external business domain boundaries. The question is: why? Research shows that more often than not, failure to realize business strategies is not because a given strategy is ill-conceived but more often due to the scope and impact of those strategies being vague or unknown. This issue becomes magnified in scenarios where the impacts of a strategic directive extend beyond a planning team’s line of sight and require cross-business coordination and collaboration. In other words, the inability to realize business strategies is oftentimes the result of doing the wrong things in the right places and the right things in the wrong places, turning good ideas into failed projects, lost opportunities, and wasted investments.

Consider an example from a US federal government agency that highlights the need to hone in on strategic objectives, programs, and related investments on clearly defined aspects of the business from the start. An intellectual property (IP) office sought to transform cross-agency and public engagement by creating a highly transparent business ecosystem across the agency, along with its partners and constituents. The program scaled up to over a dozen projects across multiple business units, teams, and technologies, with each team centered on a particular objective and scope of impact. One team, in particular, worked toward transforming the processing of international registrations across the agency, including engagement with a third-party global organization.

Program executives assigned the end-to-end transformation of the international registration value stream to a team of business analysts and solution delivery personnel. While program leadership designated the scope of the effort to a specific value stream, enabling capabilities, and stakeholders, the analysts ignored the directive in favor of a “blank page” approach. Analysts met with business subject matter experts and legacy analysts, the latter of which directed the team to concentrate on constituent petitions as a priority, with the source of this diversionary thinking resulting from constraints of the current environment. International registration transformation was, in fact, supposed to eliminate the need for costly, time-consuming constituent petitions, except where essential.

A routine review by program management discovered that the project team had invested nearly three months of time on petition processing, while ignoring its primary focus on international registration transformation. Indeed, another project team had mobilized to work on end-to-end petition processing transformation, framed by an entirely different value stream. In short, the blank-page approach taken by the analyst team resulted in lost time, wasted investment, and, worst of all, alienation of business stakeholders.

What does this story have to do with the use of business architecture to establish an agile organization? Simply put, the false start exemplified by the wayward project team in this story repeats itself dozens or even hundreds of times at medium-to-large enterprises annually, resulting in an endless spiral of ineffective strategy realization and lost opportunities. Business architecture changes the game by enabling organizational agility through effective, coordinated translation of business directives into targeted results from strategy formulation through strategy realization. It allows organizations to frame the scope of business strategies, programs and projects, and related investments from the start in clear, unambiguous terms. Indeed, business architecture lays the foundation for expediting strategy formulation through strategy realization, ensuring that business investments center on doing the right things in the right place at the right time.

The Path to Successful Strategy Realization

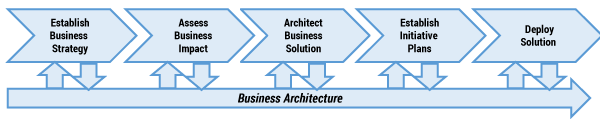

Business architecture helps organizations shift toward becoming more agile from multiple perspectives. It plays a vital role throughout the strategy realization path to increase the speed and effectiveness with which strategies become translated into initiatives, and with which initiatives introduce working changes to the business environment. Figure 1 shows an enterprise perspective on strategy realization for an organization, which occurs continually as a business implements strategies, transformations, and related business directives. End-to-end strategy realization requires many people to work together seamlessly across five stages; this includes teams centered on strategy, customer experience, architecture, product management portfolio management, program and project planning, business analysis, business process, organizational design, and execution. Business architecture is a relatively new addition to the ecosystem of strategy realization, but has a valuable role in all five stages, especially, but not solely, in Stages 2 and 3 (Assess Business Impact and Architect Business Solution).

These two stages are often skipped when organizations jump from establishing business strategy to executing projects in order to “execute faster.” However, what may appear to be a decision to expedite delivery timelines actually requires an even larger investment of time, and often budget, later, when extra effort is needed to get the organization back on track after implementing a misaligned solution, or when it takes additional time to make a new change because redundant solutions add to overall environmental complexity. The intangible impact of these decisions can also include customer experience issues, business stakeholder fatigue, and even regulatory or reputational risks.

In the first stage, Establish Business Strategy, business architecture can inform strategy formulation, identifying new options for business model evolution. This stage can also help identify potential impacts of strategic options as they are being defined in order to quickly narrow down to viable options, resulting in significant time and mindshare saved in the long run.

In the next stage, Assess Business Impact, business architecture offers an invaluable enterprise-level business lens that allows strategy impacts to be comprehensively assessed for the entire organization, across all business units and products, internally and externally. Indeed, Stage 2 exposes the “butterfly effect” of all value stream and capability changes necessary to enable a given strategy, fanning out to highlight the effects on other strategies, stakeholders, new or existing products, policies, current or planned initiatives, processes, and, assuming there is alignment with the IT architecture, technologies.

Having a high degree of transparency of the full scope of the enterprise empowers teams to work together in new ways across organizational boundaries, versus each team translating the strategy in isolation and implementing its own projects. This leads to the third stage, Architect Business Solution. Here, business and architecture teams work together (across organizational boundaries, where necessary) to design changes to the business and technology environment or to design new business solutions for any affected components, such as value streams, capabilities, products, and system applications. This perspective represents a significant shift in thinking. It is an important step forward for creating an agile organization because it ensures that the right solutions are built based directly on the business strategy and built only once in an integrated manner.

For example, the IP organization mentioned earlier was able to bring various people together from across the agency as well as its partners and constituents to comprehensively design the international registration value stream and enabling capabilities versus multiple departments and stakeholders trying to solve the problem in their own silos. In this scenario, capabilities were automated once and reused over and over again across various projects and solutions as required by a given strategic directive. One last point regarding Stage 3: this is the point where organizations can truly engage in design thinking based on a well-defined strategy and highly transparent impact points. The degree of transparency provided by business architecture lays the fertile groundwork for exploring a wide range of stories and what-if scenarios across the business ecosystem.

Once a business solution has been designed, Stage 4, Establish Initiative Plans, leverages business architecture to determine how to best allocate the full scope of work across initiatives, which often break down into multiple programs and projects with clearly defined scope and delivery sequence. When organizations skip Stages 2 and 3, the resulting projects are often overlapping, sometimes even contradicting each other, and may not be sequenced effectively. Often, the scope of a given program or project is too large or too small, but implementation teams discover this too late in the cycle to convince management to retrench. This situation can even happen when people actively collaborate across initiatives because they are limited by a fragmented, opaque understanding of the bigger picture and organizational constraints.

At the beginning of Stage 4, the scope of each initiative is framed by concrete changes to the architecture, with a clear articulation of what needs to change or be created using the common architectural components (i.e., value streams, capabilities, and applications). This activity requires business, architecture, and planning teams to work closely together, and again represents a significant shift in thinking related to how and when initiatives are defined. It ensures that initiatives are scoped in the right way and delivered at the right time. Our IP case study and the wayward project team that centered on petitions instead of the defined architectural focal point for the initiative provide an example of what can happen when this top-down approach is not used (or is disregarded): countless weeks, months, or years of precious time and resources are wasted with zero business value delivered.

Finally, in Stage 5, Deploy Solution, each initiative goes through its usual cycle of execution. Regardless of development method used, waterfall or Agile, the business architecture ensures that project teams have the right focus at the right time. Business architecture also provides a reusable framework for defining, tracking, and aligning business requirements, user stories, and deployed software solutions. The next section articulates in detail the value that business architecture can bring to agile execution approaches.

The Value of Business Architecture in Agile Execution Approaches

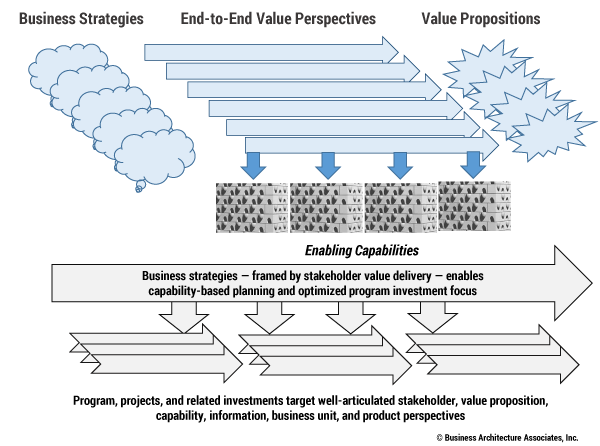

Expediting strategy definition through strategy realization requires a clearly defined, end-to-end business focus that articulates the specific investment targets associated with a given business objective. Figure 2 highlights this perspective. A series of objectives shown to the left are handed over from business executives. Planning teams associate the objective with a given value proposition (in the IP example, obtaining an international registration), which then becomes the focal point of the overall planning effort and investment.

Figure 2 depicts the value streams as the focal point of the analysis. Value streams are associated with external and internal stakeholders and enabling capabilities, which in turn are associated with business units, third parties, information used by enabling capabilities, policies linked to capabilities, and the technologies that automate the enabling capabilities. Through these connections, the business ecosystem impacted by the originating strategy comes into clear focus, which in turn frames the investment targets and program scope.

In the IP investment example, the agency sought to ensure total transparency of the international registration value proposition while expediting delivery of the end-value proposition. In this example, that meant reducing the need to file a petition unless absolutely necessary. The business objective pointed to the value proposition of an international registration, covering every applicable international jurisdiction. The value proposition pointed to the registration value stream, which engaged a cross-section of external and internal stakeholders, including the applicant; enabling capabilities; business units, including partners; and related information.

The resulting project was entirely framed around this value stream and related business perspectives. A second parallel project and team directed its energy and efforts on the value stream to decide a petition, thereby avoiding conflicts or overlap of the work being done and results being achieved. The intentional points of overlap involved shared enabling capabilities across the value streams and projects, which highlights a key advantage in applying the business architecture approach: shared enabling capabilities point to opportunities to establish reusable software deployments. Each project and project phase deployed or enhanced capability-aligned software services that became reusable in later project phases, allowing the program to scale to concurrent projects while reducing delivery timelines.

Business Architecture Provides Common Vocabulary and Mental Model

In his 1833 book On War, Carl von Clausewitz states that “the first task of any theory is to clarify terms and concepts that are confused…. Only after agreement has been reached regarding terms and concepts can we hope to consider the issues easily and clearly, and expect others to share the same viewpoint.” Expediting strategy definition to strategy realization also requires a common vocabulary to be leveraged across all business units or even external stakeholders who may be involved in developing solutions and helping the organization achieve its goals. This vocabulary must include a rationalized view of business terms like customer, product, and agreement for most organizations as well as any industry- or organizational-specific terms. For example, the IP organization defined common terms such as, for example, intellectual property, policy, research, classification, proceeding, and petition, as part of its business architecture.

Rationalizing and defining the business vocabulary is one of the most introspective and challenging things an organization can do. However, the shared vocabulary and mental model of an organization, which business architecture establishes through capability, value stream, and information mapping at the core, save immeasurable time that is otherwise lost in conversations where people talk over each other or solutions are developed that do not meet business needs. Fortunately, business architecture reference models have evolved to the point where the time and effort it takes to establish a business architecture baseline is dramatically streamlined. Moreover, a rationalized view of an enterprise is the foundation for any organization that plans to shift toward becoming a cognitive enterprise, where the cognitive enterprise is a learning organization with a centralized knowledgebase that evolves and accrues business intelligence over time.

Business Architecture Fosters Strategy/Initiative Alignment and Prioritization

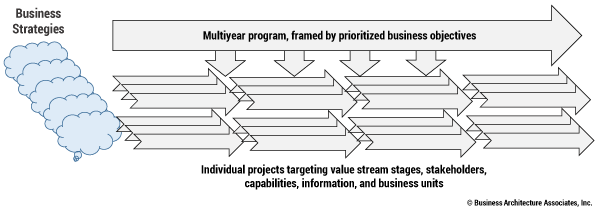

Consider that a given organization will often have many strategies it wishes to address. In the IP example, the executive team had a long list of strategic objectives that it had to prioritize across a five-year program and dozens of projects and project teams. The two examples discussed thus far involved one project designed to enable expedited, effective international IP registration with a second project centered on streamlining effective petition resolution. To accommodate executive directives and priorities, the agency had to execute several parallel projects under a single program, as illustrated in Figure 3.

In the IP transformation scenario, the overall program ensured that projects moved very quickly from stated objective to the delivery of work, which applied Agile project delivery principles leveraging two-week sprints, Agile epics and user stories, daily standups, backlog management, and Scrum-of-Scrums. With one exception of the case where the initial international registration project team went rogue and refused to leverage the value-stream-and-capability-framed project perspective, work progressed efficiently and smoothly from value stream stage to stage, across targeted stakeholders, focused on automating or otherwise improving enabling capabilities at each phase.

The example of the project team that went rogue makes a strong case for using business architecture to help frame business strategy realization. While project teams leveraged business architecture–framed priorities to expedite startup time, streamline business discussions, and reduce exploratory scoping, the rogue team wandered lost for three months, working on the entirely wrong business focal point and costing the organization time, money, and business credibility. In other words, teams that leveraged the business architecture moved with agile aplomb while the rogue team struggled to get its footing, demonstrating how business architecture makes a real difference between the expedited, successful delivery of business value and a series of failed investments and commitments.

Business Architecture Scopes Initiatives and Provides Deployment Framework

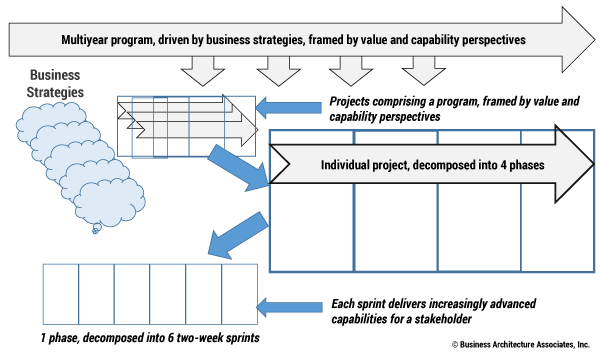

In the IP example, the overall program framed a collective set of strategies to be delivered in coordinated fashion, where each project targeted a given value stream or subset of a value stream, and work was prioritized by stakeholder and capabilities for each value stream stage. Consider the specific prioritization and sequencing of work associated with the IP registration value stream. Projects decomposed into four phases, each of which delivered quarterly. Each phase decomposed into a series of two-week sprints. Each sprint targeted delivery of certain capabilities for a given stakeholder, in the context of the value stream stage framing that piece of work. Figure 4 depicts the program, project, phase, and sprint decomposition concept.

In the IP case, the IP examiner was the initially prioritized targeted stakeholder within a value stream stage of the registration value stream. Project teams delivered capability-related enhancements and automations for the IP examiner over a period of multiple project phases, until there was a deployable solution for the attorneys to perform their jobs. The project prioritized additional stakeholders across business units, sprint after sprint, phase after phase, until the solution extended across all stakeholders for essential capabilities across that value stream.

This overall framing of programs, projects, phases, and sprints highlights the value business architecture brings to an organization using Agile delivery approaches. The IP program was employing Agile development techniques in both the challenged project associated with the rogue team and each successful project. When the rogue team on the international registration project was replaced with a new team that embraced and leveraged the business architecture, that project quickly regained its footing and began to deliver value across the stakeholder ecosystem. The organization achieved its overall strategic objective for the applicant as well as the internal stakeholders via project evolution and solution deployment. In other words, business architecture clearly made the difference between successful deployment of this project versus a challenged attempt at this project.

Business Architecture Connects the Dots Across Strategies, Architectures, and Initiatives

Business architecture is not only valuable within the context of one program; it also has the unique ability to connect dots across programs, which can be challenging in its absence. The shared enterprise-level business lens of business architecture, with a focus on value streams and capabilities, becomes the common key for cataloging changes being made as a result of any strategy, target architecture, or initiative. This formal framing of strategy realization makes it possible to definitively identify when changes are being made to the same area of the business, thereby uncovering opportunities for new collaborations, shared solutions, and coordinated decision making, such as when to pull back when too much change is being introduced for a given stakeholder.

The IP example highlights additional points in terms of connecting the dots from a holistic perspective. Having enterprise-wide visibility into all strategies and potential changes centered on international registration gave the IP program team a quick way to pinpoint additional factors that should have been considered up front, such as new treaties and regulations. Another factor was that the international work was eased by deploying a domestic IP registration solution first, which established a reusable baseline for the international solution. The program also had end-to-end visibility and impacts from a global software solution perspective. In this case, a shared database and reusable software services library emerged as a result of this overall program, meaning that the agility gained during the deployment stages of the program would be formalized and institutionalized to enable this organization to become and remain an agile enterprise well into the future.

Ubiquitous Business Architecture

One major differentiator of business architecture is that it is not constrained to internal business perspectives. The international value stream in the IP example highlights an external perspective. The original perspective of the business on international registrations essentially ended when the registration request was sent to the third-party global organization, but the value proposition was nowhere close to being achieved. Extending the applicant value delivery perspective end to end expanded and clarified the business objective. Stakeholder transparency had been constrained to internal views and lacked perspective on the third-party global organization engagement. This represented a design thinking phase of the program where no one ever conceived of establishing 360-degree visibility into work once it entered the partner domain. Yet the value stream made this external perspective blindingly apparent.

The fully expanded stakeholder perspective highlights the concept of ubiquitous business architecture where value streams are not constrained to a single organization but rather across a business ecosystem that includes other business entities. By expanding the value stream perspective through delivery of all international registrations, the agency delivered major improvements in applicant value delivery. In addition, by adding capabilities to enable application engagement across the value stream, the need to initiate related petitions was reduced dramatically, which further reduced the demands on an already overworked business unit.

In order for an organization to maximize the value of business architecture, it should leverage a holistic ecosystem perspective on business architecture. This approach focuses on stakeholder value delivery from an end-to-end perspective, which frames the value streams targeted for investment. When engaged in this approach, the basic foundation for an organization to transform itself into an agile enterprise is in place.

Introducing Business Architecture into Agile Approaches

How then do organizations begin introducing business architecture into agile execution approaches to achieve these benefits? Those organizations that already have a business architecture in place have an advantage in that they can immediately begin leveraging it to prioritize and structure an agile execution. However, this requires a relatively complete and well-structured business architecture. For example, the minimum foundation includes the definition of core value streams and capabilities decomposed down three levels, as well as value stream/capability cross-mapping for areas of the business being targeted by a given set of strategies. Another key aspect of business architecture that comes into play early in the cycle is the information, which formalizes the business vocabulary and relationships across various information concepts.

The business architecture should be created from an enterprise perspective and based on a rationalized view of business terms. From here, the business architecture may be cross-mapped to other business architecture domains, such as strategies and products, as well as to other disciplines, such as event modeling, processes, and software applications. For those organizations that do not yet have a business architecture, it can be built over time once the value stream and capability foundation is in place. Reference models expedite this effort. From there, refinements, additions, and cross-mappings to the business architecture are captured opportunistically as dictated by business priorities.

In addition, the use of business architecture must be integrated into the way people work during an agile execution. For example, product owners need to learn how to work with business architects and use the business architecture to inform prioritization, and all project teams need to learn how to consume architectural scope and input for their projects and sprints. Business analysts must become fluent in understanding and using the business architecture. Adoption in practice can be more challenging than creating the business architecture in the first place because it requires the patience and desire to introduce a new frame of reference into one’s mindset, albeit one that provides significant business transparency.

Making these types of changes is, of course, more successful when supported by other overarching measures to encourage and support people throughout the organization to shift to an agile and enterprise-focused mindset. This can include actions such as executive messaging to describe how the organization of the future will work and deliberate change management activities to help people adjust. Further measures may also be needed, such as adjusting funding mechanisms to work across organizational boundaries or adjusting employee compensation and motivational structures.

Conclusion

Organizations should leverage business architecture throughout the path to strategy realization to harmonize the execution of business direction across organizational boundaries and initiatives. Business architecture ensures that organizations do the right things that align with business priorities and are scoped and integrated effectively. Though business architecture is a relatively new addition to the ecosystem of strategy realization teams, it plays a valuable role in strategy formulation, impact analysis, business design, program definition, and agile execution. When business architecture is in place, adopted and leveraged ubiquitously, the gateway for an organization to transform itself into an agile enterprise is in place.