AMPLIFY VOL. 38, NO. 4

Is your board built to innovate? If you ask directors where the heavy lifting of governance happens, few will say it is during boardroom presentations. The real work gets done in committees — smaller, focused, often underestimated teams where ideas are tested, risks are debated, and strategy is shaped.

This is especially true when it comes to innovation. In our recent study of 249 publicly listed Brazilian firms from 2005 to 2023, we found that the way boards are structured (and how their committees are formed) has a powerful effect on innovation-related governance. Yet far too many companies continue to treat the formation of strategy, innovation, development, technology, and risk committees as a formality, not a lever.

Our findings point to a single critical message for practitioners: boards do not innovate — committees do.

Innovation & Boards

Innovation has become the new North Star of corporate strategy. From ESG (environmental, social, and governance) and AI to climate resilience and digital disruption, companies are under pressure to not just adapt but to invent the future.

Boards know this. Innovation appears on nearly every corporate agenda, and directors are under pressure from investors, regulators, and society to act boldly. Paradoxically, although every board says innovation is a priority, few have structures in place to govern it effectively.

In many companies, innovation is treated as an execution challenge for management rather than a governance challenge for the board.1 Our research reveals that board structure (specifically committee design) can make or break innovation capacity. Committees are where long-term bets are debated, risks are vetted, and strategic trade-offs are explored.2 Innovation thrives when these spaces exist and falters when they do not.

We studied Brazilian firms to understand how boards have approached innovation governance over the past two decades. What we found is clear: the way boards are structured, committees are formed, and directors are engaged matters far more than vision statements or innovation rhetoric.

This article offers a guide for boards that want to be ready for what’s next. Based on evidence and pattern recognition from real firms, we show how committee design can empower — or inhibit — innovation. If your board wants to be fit for the future, it’s time to look inward.

In today’s economy, innovation does not just need investment; it needs governance. That begins with a single question: is your board built to innovate? Boards that want to be ready for the future must ask: Do we have the right committees? Are the right people on them? Do those committees have the time, talent, and mandate to shape innovation rather than just monitor it? Innovation starts in governance, and governance starts in committees.

Boards Are Evolving & So Are Committees

Innovation governance is not static. It evolves over time and varies across boards.3 By analyzing Brazilian firms, we can see how firms have gradually embraced innovation-related committees and how trends shifted in the last two decades.

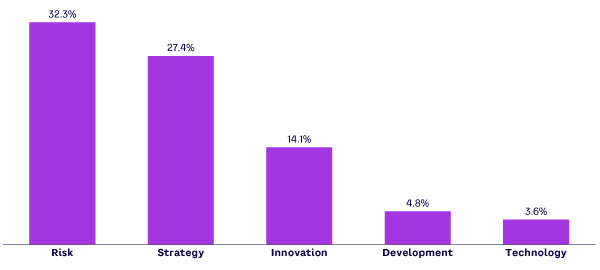

As of 2024, strategy and risk committees are the most common innovation-related structures, each appearing in more than 25% of firms in our sample. Innovation committees, in contrast, are present in just over 14% of firms, and development and technology committees are even less frequent, with 4.8% and 3.6% adoption rates, respectively (see Figure 1).

This tells us two things. First, innovation governance remains relatively underutilized in Brazilian firms. Second, when innovation is governed, it is often done indirectly — through strategy and risk rather than through focused innovation or technology committees.

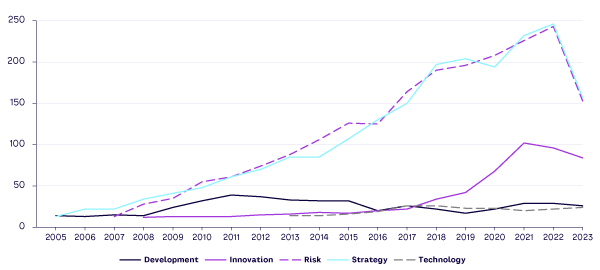

The story gets more interesting when we zoom out. Figure 2 shows the prevalence of five innovation-related committees from 2005 to 2023:

-

There’s been a steady, gradual increase in strategy and risk committees, suggesting growing awareness of strategic foresight and governance compliance.

-

Innovation committees barely existed in 2005. They began to emerge post-2015, with noticeable growth during the pandemic years and into the early 2020s.

-

Technology and development committees have increased in recent years, likely in response to digital transformation, cybersecurity challenges, and sustainability pressures.

It’s clear that although adoption remains low in absolute terms, the direction is unmistakably upward. Firms are slowly expanding their governance toolkit to include structures more directly aligned with innovation imperatives.

From Compliance to Competitiveness

In the past, committee formation was often compliance-driven, especially for audit and risk. More recently, we see a shift toward strategic governance that includes a focus on innovation. Boards are beginning to ask: “Where are we headed?” rather than just “Are we safe?”

Reflection 1: Is your sector moving fast enough to justify a technology or innovation committee? If your competitors are forming these structures and you’re not, what might you be missing?

Innovation-related board committees are not about micromanaging R&D. They are about ensuring the board is equipped to ask the right questions, evaluate emerging risks and opportunities, and provide sustained oversight on innovation initiatives.

Suzano Group, the world’s largest producer of cellulose, is a pioneer in this area. It created a Strategy and Innovation Board advisory committee that played a key role in guiding the company’s diversification into wood-based cellulose fibers. The committee was instrumental in a move to integrate innovation with sustainability, leading to the concept of “innovability” that now guides Suzano’s strategy.

Tip 1: Benchmark your board against peers in your sector. Review annual reports, governance disclosures, and investor presentations from leading competitors. If they have established innovation or technology committees (and you have not), that is a signal to reassess. Use this insight to initiate a conversation at the board level: What governance structures would better align us with where our industry is heading?

We identified three actions critical to ensuring that innovation-related board committees reach their full potential.

1. Bigger Boards, Better Oversight?

One of the most common critiques of large boards is inefficiency. More voices, more politics, more slowdowns — or so the thinking goes.4 But when it comes to fostering innovation, board size is not necessarily a burden. In fact, it can be an advantage. Our study found that larger boards are significantly more likely to form innovation-related committees, including those focused on strategy, risk, development, and technology. The reason is straightforward: large boards have the capacity to distribute workload, draw on more diverse expertise, and form specialized subgroups that dig deep into complex topics.

Committees create focus and accountability. Think about the innovation agenda. It often involves navigating long time horizons, technical ambiguity, and organizational resistance. A full board, meeting quarterly, is unlikely to give these issues the airtime or attention they need. But a dedicated innovation or technology committee, empowered and properly staffed, can.

For example, the Strategy and Innovation committee at Brazil’s Embraer, the third world’s largest manufacturer of civilian aircraft, played an important role in creating and supervising Embraer-X, a spinoff dedicated to corporate entrepreneurship based on disruptive technology. This move led to Eve Air Mobility, a New York Stock Exchange–listed independent company developing an electric vertical takeoff and landing aircraft. The size of the board, from nine to 11 directors, allows for the effective operation of advisory committees.

This specialization also sharpens accountability. When a firm forms a technology committee, it signals that digital transformation is not just an operational issue; it’s a board-level concern. When it creates a development committee, growth is not just a KPI; it is a governance priority.

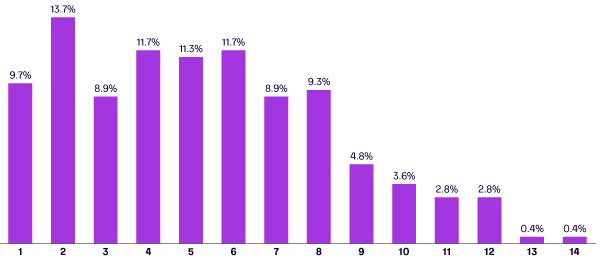

We found that boards with eight or more members were significantly more likely to form multiple, well-differentiated committees. This runs counter to the minimalist trend some firms have embraced in the name of efficiency. But innovation is not always efficient. It is an iterative, long-term, resource-intensive process.

The real question is not whether the board is large or small. It is whether it has the structural agility to form the right committees, at the right time, with the right people.

Reflection 2: Does the size of your board allow the formation of committees beyond audit and compensation? If not, how are innovation-related risks and opportunities being governed?

Some boards resist expansion, fearing complexity. But our study found that larger boards have more innovation capacity because they can staff more specialized committees. With the right structure, bigger can mean smarter, all else being equal. However, our sample revealed that the prevalent trend is toward smaller boards (see Figure 3).

Tip 2: Consider expanding your board if innovation, risk, or digital transformation are strategic priorities. More seats can mean more depth.

2. When the CEO Wears 2 Hats

In many firms, the CEO serves as board chair. This model is often justified as a way to streamline leadership and align strategy.5 In theory, one person holds the vision, leads the execution, and oversees governance. In practice, this concentration of power brings risks, especially for innovation.

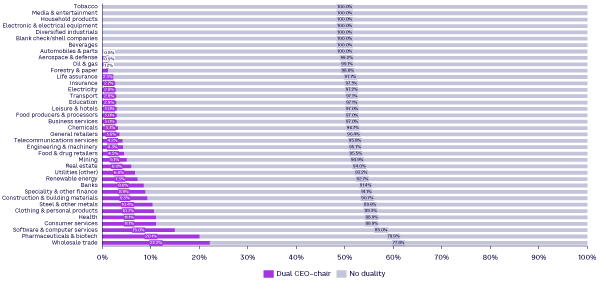

Our findings show that “CEO duality” is positively associated with the formation of strategy committees. That’s logical: when a CEO also chairs the board, they are more likely to formalize support structures around their vision.6 But we saw no statistically significant link between CEO duality and the creation of innovation-related committees, such as innovation, technology, development, or risk.

With centralized power comes narrow focus.7 The implication is clear: CEO duality encourages top-down strategic focus but does not necessarily support the bottom-up, cross-functional structures that innovation requires. In fact, it may hinder them. When one person sets the agenda and chairs the discussion, there is less incentive to form committees that could challenge, complicate, or diffuse that authority.

This is not a theoretical concern. Innovation often involves friction: new ideas, uncomfortable trade-offs, and ambiguous outcomes. Committees provide a space where these tensions can be navigated without much worry about executive control. When dual roles dominate, the board may default to consensus rather than critical inquiry.

CEO duality is not inherently bad. But boards must be deliberate about how they balance that structure. If your CEO is also chair, are there sufficient independent voices leading key committees? Are innovation efforts being discussed in spaces where genuine debate is possible?

Reflection 3: If your CEO is also chair, who is leading your innovation-related committees? Do they have true independence?

CEO duality boosts the likelihood of forming a strategy committee (perhaps to reinforce the CEO’s vision), but it does little for forming other innovation-relevant committees (see Figure 4).

Tip 3: If your CEO is also board chair, ensure committee leadership is intentionally balanced. Without counterweights, innovation oversight may skew strategic.

3. The Hidden Cost of Busy Directors

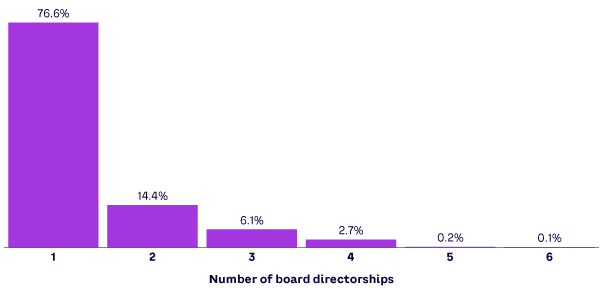

The third major finding from our study speaks to a governance issue that many boards overlook: director busyness. A “busy board” refers to directors who serve on multiple boards simultaneously.8,9 These directors often bring experience, connections, and credibility. But they also bring limited time and attention — two resources innovation governance can’t do without. In other words, directors engaged in too many boards have limited time to contribute.

We found that busy boards are significantly less likely to form innovation and technology committees. In fact, the busyness of directors was one of the strongest negative predictors of committee formation in these areas.

Expertise without capacity is a risk. Many busy directors are appointed because of their industry knowledge or strategic background. But when they are stretched across three, four, five, or even six boards, their actual contributions to any one committee diminish.

This matters most in the context of innovation. Committee work in this domain is not passive.10 It requires engagement with emerging trends, scrutiny of experimental initiatives, and the ability to ask informed, forward-looking questions. Directors who are overloaded lack the mental bandwidth to do this well. Boards can suffer from a kind of “credential trap” — assuming that prestige equals performance.

Boards should start looking not just at who is on their roster, but how available they are. It may be time to rethink director recruitment criteria to include both diversity of background and availability to engage deeply in committee work.

Reflection 4: How many boards do your directors sit on? Are you (along with other board members) prioritizing prestige over participation?

It is tempting to fill boards with high-profile names. But our data shows that directors who sit on multiple boards are less likely to support innovation and technology committees (see Figure 5).

Tip 4: Monitor your board’s “busyness.” Even the best minds cannot contribute if they are stretched too thin.

Playbook for Boards That Want to Innovate

If there is one lesson to take away from our study, it’s that innovation governance requires structural intention. Great boards are not just well composed, they are well organized. This shows up in how they form and operate their committees. Based on that, we propose the following four-step playbook for boards that want to govern innovation effectively.

Step 1: Establish Committee(s)

Don’t wait for an innovation crisis to form a technology or development committee. The most forward-thinking boards establish these structures proactively — before disruption hits. This allows the board to develop institutional fluency around emerging trends and support innovation long before it’s urgent.

Step 2: Reassess CEO Duality

In boards where the CEO is also chair, it is essential that innovation-related committees be led by independent directors who are empowered to surface tensions, challenge assumptions, and guide experimentation. Innovation needs both alignment and challenge.

Step 3: Audit Director Workloads

Avoid the temptation to overload innovation committees with prestigious leaders who don’t have sufficient time to participate. Instead, assign members with capacity, curiosity, and courage, and make sure their work is meaningfully integrated into board deliberations.

Step 4: Support Smaller, Focused Committees

Too often, committee formation is seen as compliance. But the best boards treat it as strategy. They ask: What does our committee structure say about our priorities? Where do we need deeper engagement? What signals are we sending to management and the market?

Conclusion

Our findings about Brazilian companies suggest that the lessons learned may apply to other emerging economies, especially those where governance practices designed to leverage innovation performance are developing. This includes economies such as India, South Africa, Poland, and Hungary, as well as Latin American countries like Argentina, Colombia, and Mexico.

The innovation economy is not just changing products and services, it is changing how organizations must be governed. It demands faster cycles, deeper expertise, and more distributed decision-making. For boards, this means moving beyond the model of oversight as occasional supervision. It means building structures that engage with innovation directly.

Innovation does not thrive on vision statements alone. It needs risk committees that understand technology, development committees that support growth, and strategy committees that are not afraid of reinvention. All that begins with a single question: is your board built to innovate?

Acknowledgment

The authors are grateful to Professor Randall S. Peterson (London Business School) for comments and inspiration. Additionally, we thank Janaina Pamplona, Flávia Consoni, Roberto Hermann, and Tommy Clausen for their support. The authors retain full responsibility for the contents of this article.

References

1 Brown, Gerry, and Randall S. Peterson. Disaster in the Boardroom: Six Dysfunctions Everyone Should Understand. Springer, 2022.

2 Peterson, Randall S., and Pedro Fontes Falcao. “Build a Better Board.” MIT Sloan Management Review, 26 September 2024.

3 Harrison, J. Richard. “The Strategic Use of Corporate Board Committees.” California Management Review, Vol. 30, No. 1, October 1987.

4 Daily, Catherine M., Dan R. Dalton, and Albert A. Cannella. “Corporate Governance: Decades of Dialogue and Data.” Academy of Management Review, Vol. 28, No. 3, 2003.

5 Daily, Catherine M., and Dan R. Dalton. “CEO and Director Turnover in Failing Firms: An Illusion of Change?” Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 16, No. 5, June 1995.

6 Withers, Michael C., and Markus A. Fitza. “Do Board Chairs Matter? The Influence of Board Chairs on Firm Performance.” Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 38, No. 6, September 2016.

7 Hambrick, D.C., and S. Finkelstein. “Managerial Discretion: A Bridge Between Polar Views of Organizational Outcomes.” Research in Organizational Behavior, Vol. 9, 1987.

8 Chen, Kevin D., and Andy Wu. “The Structure of Board Committees.” Working paper 17-032, Harvard Business School, 2016.

9 Field, Laura, Michelle Lowry, and Anahit Mkrtchyan. “Are Busy Boards Detrimental?” Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 109, No. 1, July 2013.

10 Chang, Ching-Hung, and Qingqing Wu. “Board Networks and Corporate Innovation.” Management Science, Vol. 67, No. 6, August 2020.