Part II of this series described the conceptual, IDEAL architecture required for a modern, all-inclusive information management environment. I proposed that such an architecture provides the blueprint for a data lake, which should be considered from the point of view of the three “thinking spaces”: information, process, and people. The architectural principles are encapsulated in the acronymic name: integrated, distributed, emergent, adaptive, and latent. Latent, or hidden, implies that these three thinking spaces are not a representation of how this architecture will be built. That it is the role of a logical architecture.

A logical architecture provides the foundation for implementation — independent of physical and/or product constraints — of the decisions and agreements made at the conceptual level between business needs and visions and IT’s technological realities and opportunities. This is the REAL architecture, an acronym conveying the idea that, whereas the conceptual architecture provides a view of what we'd like to have, the logical architecture has to be achievable. REAL stands for:

- Realistic — implementation can begin today with existing technology

- Extensible — the architecture is open to extension and expansion as technology evolves

- Actionable — the actions required of the business and IT are clearly identified

- Labile — the architecture is flexible to allow changing needs as the system evolves

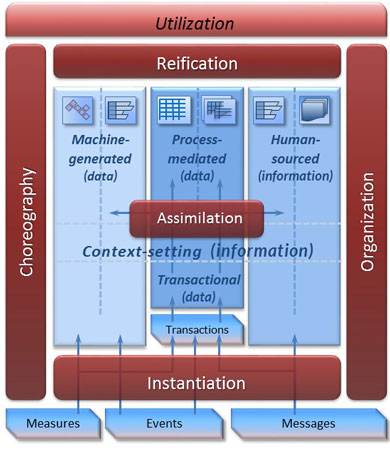

Figure 1 — The REAL data lake architecture.

This logical level of architecture, shown in Figure 1, is used mainly — and perhaps exclusively — by IT and gives a view of the processes needed to create, maintain, and use business information. That’s information and process. There is no people component in this architecture picture. IT is not in the business of building people — yet. Robotics and artificial intelligence may lead to that eventuality in the longer term.

The information components of the REAL architecture (in blue) consist of pillars of information, rather than the layers shown in traditional data warehouse architectures. I show three pillars, although there could be more in an actual implementation. Each pillar is optimized for a particular type and use of data. Machine-generated data relates strongly to the Internet of Things today, but also covers data from internal machines and sensors. Human-sourced information supports social media and other textual and multimedia sources. Process-mediated data is the traditional transactional data created by the control and management processes of the business. Spanning across these information pillars is a set of context-setting information (CSI) — the new, more meaningful, name for metadata introduced in Part III.

Note the distinction between data and information, seen in the names of the three pillars: information is more human oriented, while data is related to machine and computer sources. It also appears in CSI, which is actually information and it provides the context for other information and processes. This CSI, together with the assimilation component that sits in the middle of the logical architecture, provides the means by which these are pillars rather than silos. Pillars have integrated data as a core principle, as opposed to silos, which lead to disintegrated data.

Process components (in brown) surrounding the information pillars relate to the creation of and access to that information. The central component ensures information consistency. Three of these adaptive process components deal particularly with information preparation and use: instantiation gathers data from the external world; assimilation reconciles and cleanses information; and reification enables virtualized access to data in the different pillars.

There exist three distinct inputs from the real world — measures, events, and messages — that pass through the instantiation component in order to end up in information pillars. Transactions, however, appear inside the surrounding process components, because transactions — the key inputs of traditional process-mediated data — are actually created within the business and actually represent legally binding interactions with internal and external parties, based on the content of measures, events, and messages.

Pictorially, Figure 1 looks rather like a blue data lake bounded by brown earthen levees, recalling the discussions about the need for a viable structured approach in Part I. The REAL architecture thus offers a logical view of all the information types and management components needed. It makes a further and vital contribution to data lake thinking. This architecture clearly demonstrates that not all data/information in the lake is the same. Some data must be highly structured and defined in advance to support business consistency and meaning. Other data/information may remain highly variable or loosely structured to support agility. These different data/information types must be stored and managed in different databases or data stores, optimized for their varied structures and uses.

The three remaining components — choreography, organization, and utilization — deal with the creation, management, and use of the processes through which business (and IT) run and manage the business. These are the topics of the next article in the series.