AMPLIFY VOL. 37, NO. 1

Humble leaders are self-effacing, empathetic, able to recognize the contributions of others, and can admit their mistakes.1 Hamdi Ulukaya is a humble leader. He immigrated to the US in 1994 from Turkey. In 2005, he founded a company in upstate New York. Ulukaya contracted to buy raw materials locally and hired local people. He provided above-minimum wages, healthcare, and other benefits to full-time employees, started a 401(k) plan, and gave 10% of the company’s profits to charity. Since then, Ulukaya has been a prolific philanthropist.2 Perhaps because he is self-effacing, his name is unknown, but his company, Chobani, has a worldwide reputation.3

Now, some leaders combine humility and narcissism.4,5 Steve Jobs is an example.6 He exhibited narcissistic behavior: self-focus (black turtleneck and blue jeans to distinguish himself from suited executives7), grandiosity (a super yacht named “Venus”), along with stunning cruelty and lack of empathy toward subordinates, friends, and family.8 In justifying his theft of the basic ideas for the Macintosh personal computer from Xerox, Jobs compared himself to Picasso: “Picasso had a saying — ‘good artists copy, great artists steal’ — and we have always been shameless about stealing great ideas.”9

According to Alexander Kaufman, writing in the Huffington Post (reprinted in Inc.):

Until he was fired in 1985, Jobs was known for being extremely demanding on people around him, including then-CEO John Sculley. “That was part of his greatness,” William Simon, coauthor of iCon: Steve Jobs, the Greatest Second Act in the History of Business, told ABC News in 2011. “But he drove people too hard … Being gentle was not part of his demeanor.” By the time Jobs returned to Apple in 1997, he had learned to balance his leadership style.10

It is tempting to see two forces at work in this story. Due to his narcissistic tendencies, Jobs was able to take risks, innovate, and indulge in a truly grandiose vision of his place in the world. Yet, due to some degree of humility, he was able to effectively work with people and avoid the narcissistic self-destruction that befell other leaders. A mystery remains. Jobs was either an important but solitary historical figure or an example of a class of visionary leaders who have shaped the future. The purpose of this article is to solve this mystery.

Methods

The origin of this investigation was a randomized list of 400 upper-echelon CEOs that had been used in previous research. Beginning at the top of the list, eight trained research assistants collected documents and coded them for CEO humble behavior. The final database consisted of the first 190 CEOs on the list.

Researchers and practitioners typically gain data from students, employees, clients, and lower-level managers using surveys, questionnaires, interviews, observation, formal tests, and focus groups. Acquiring data from upper-echelon leaders such as CEOs is difficult. Standard techniques are usually not available, and leaders are wary of giving out proprietary information that may be used by competitors.11 However, leaders make speeches, give out selected interviews, conduct conference calls, publish press releases, communicate via annual reports, and make use of social media. These materials can be analyzed by content analysis. Content analysis involves two phases: (1) the development of procedures to reliably and validly analyze documents and (2) the actual coding of the materials.12

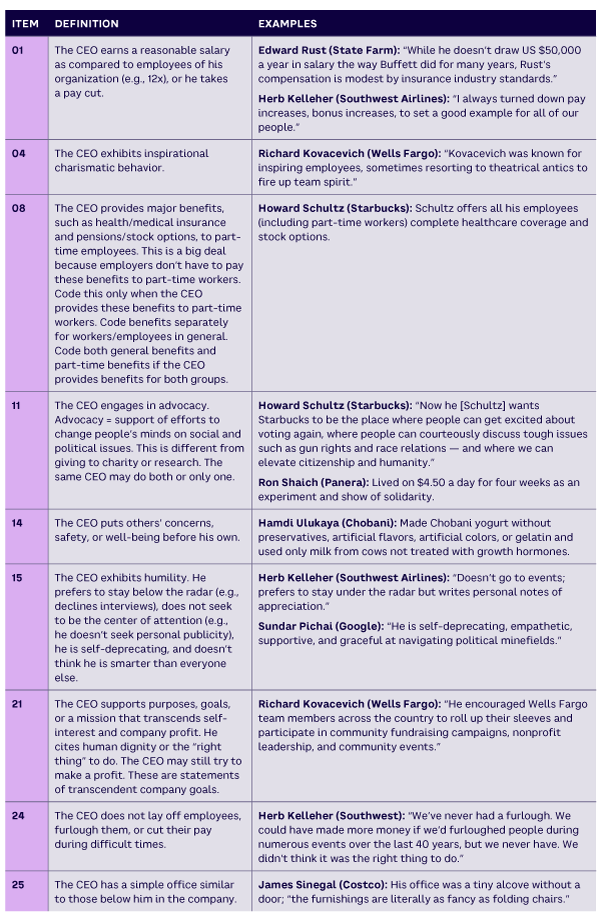

In previous CEO research, trained research assistants and I had developed a list of descriptors of humble CEOs. Using the descriptors, the assistants examined biographical materials on the Internet and collected instances of humble behavior. They coded texts using the items, eliminated some items, and created a 35-item checklist of humble CEO behavior. For this project, a different group of eight research assistants eliminated some items from the original list, collapsed some, and added new items. They prepared an eight-page coding manual with 31 items, item definitions, and examples from Internet documents. A subset of these items appears in Table 1.

The research assistants collected seven or fewer third-party documents for CEOs on the randomized list. These documents did not include CEO interviews and conference calls in the database. We wanted appraisals of CEO behavior from observers, not the CEOs themselves.

Using the coding manual, the research assistants coded the documents. Four students coded one subset of CEOs; the second set of four coded a second subset. That is, four students coded each CEO in their subsample. I found that the coding of one student was unrelated to the coding of other members of the student’s team coding the same materials. The data from this student was eliminated.

The result was independent scores for 190 CEOs. I examined the scores for each CEO. In a few cases, scores deviated substantially among coders for the same CEO. Two research assistants then recorded the scores for these CEOs. Once the coding was finished, the final 31-item scores for each CEO were averaged. CEOs with a total score less than one were labeled low humility. CEOs with a humility index between one and 12 were labeled high humility.

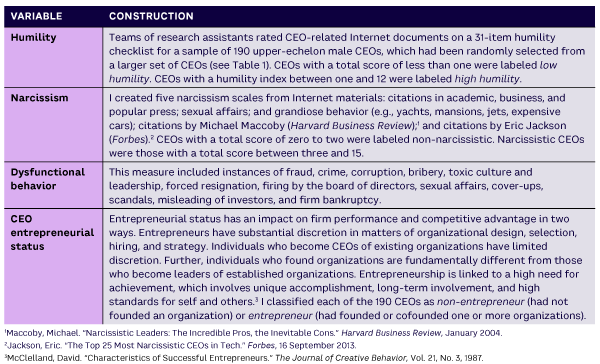

Using content analysis procedures and Internet materials, I created measures of narcissism, dysfunctional behavior, and entrepreneurial status. Table 2 summarizes the content analysis procedures used.

Results

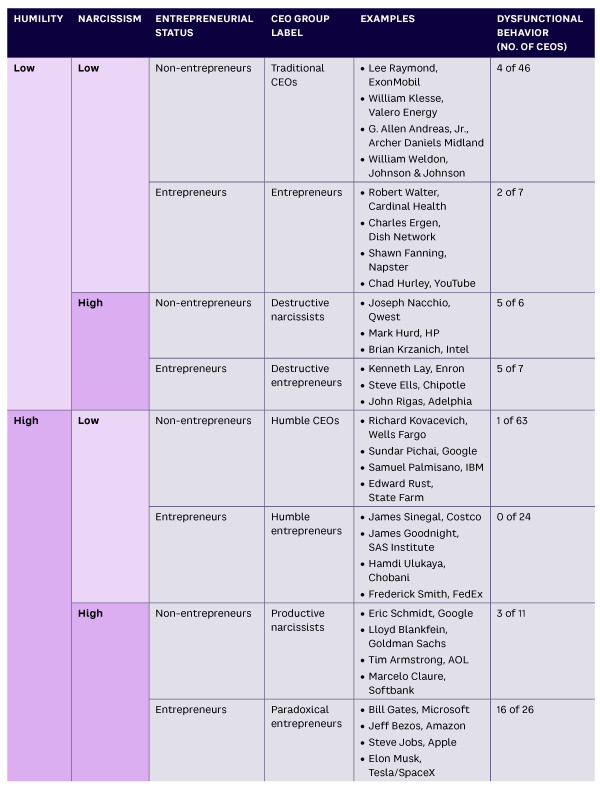

Eight homogeneous, mutually exclusive groups of CEOs emerged from the data analysis (summarized in Table 3):

-

Traditional CEOs (low humility, low narcissism, non-entrepreneurs) — individuals who had worked their way up the ranks of traditional companies, such as ExxonMobil, Valero Energy, Archer Daniels Midland, Johnson & Johnson, Kraft Foods, and Coca-Cola. Four of 46 had been implicated in one or more forms of dysfunctional behavior.

-

Entrepreneurs (low humility, low narcissism, entrepreneurs) — included Robert Walter (Cardinal Health), Charles Ergen (Dish Network), Shawn Fanning (Napster), and Chad Hurley (YouTube). Two of seven reputedly had engaged in dysfunctional behavior.

-

Destructive narcissists (low humility, high narcissism, non-entrepreneurs) — included Joseph Nacchio (Qwest), Mark Hurd (HP), Brian Krzanich (Intel), and James Cayne (Bear Stearns). Five of the six CEOs in this group had been implicated in dysfunctional behavior, including decisions leading to the demise of their organization, toxic policies, sexual harassment cover-up, conviction on 19 counts of insider trading, and resignation after an affair with an employee.

-

Destructive entrepreneurs (low humility, high narcissism, entrepreneurs) — included Kenneth Lay (Enron), Steve Ells (Chipotle), John Rigas (Adelphia), and Travis Kalanick (Uber). Fraud, conspiracy, toxic culture, sexual assault, stealing from the company, and a US $25 million fine to resolve criminal charges distinguished five of seven entrepreneurs in this group.

-

Humble CEOs (high humility, low narcissism, non-entrepreneurs) — included CEOs such as Richard Kovacevich (Wells Fargo), Sundar Pichai (Google), Samuel Palmisano (IBM), Edward Rust (State Farm), Alan Mulally (Ford), Craig Jelinek (Costco), and Doug Conant (Campbell Soup Company). These CEOs differed from traditional CEOs. Only one of 63 had been involved in dysfunctional behavior, and all exhibited a considerable degree of humble leadership. Mulally is a good example. According to a Forbes article, “Mulally does not believe in top-down control when it comes to the culture of the organization. Coaching, facilitating, and leading with humility, love, and service are table stakes for him.”13 Conant, former CEO and president of Campbell Soup Company, is another example. According to Christine Porath and Conant, writing in Harvard Business Review, “The best way to truly win the hearts and minds of people, and generate huge returns for your organization and its stakeholders, is by leading with civility. This means spending a considerable amount of effort acknowledging people’s contributions, listening better, respecting others’ time, and making people feel valued.”14

-

Humble entrepreneurs (high humility, low narcissism, entrepreneurs) — included James Sinegal (Costco), James Goodnight (SAS Institute), Ulukaya (Chobani), Frederick Smith (FedEx), Tony Hsieh (Zappos), Richard Campo (Camden Property Trust), and John Mackey (Whole Foods). Seven traits typify these humble entrepreneurs:

-

Modest lifestyle. I found no Internet references to extravagant lifestyle, such as private jets, yachts, expensive clothes, or private art collections. However, there were descriptions of modest lifestyles. According to Business Insider, Sinegal’s clothes came from Costco. His office was a “tiny alcove without a door; the furnishings are literally as fancy as folding chairs … Sinegal even answered his own phone instead of employing a secretary to do it.”15

-

Relatively modest compensation. Sinegal stated that a CEO should earn roughly 12 times the salary of the average employee. His base salary at Costco was $350,000.16 According to Celebrity Net Worth, Sinegal’s total compensation in 2010 was about $3.5 million, including base salary, bonuses, and stock options.17 By comparison, according to the Economic Policy Institute, “Average top CEO compensation was $15.6 million in 2021, up 9.8% since 2020. In 2021, the ratio of CEO-to-typical-worker compensation was 399-to-1 under the realized measure of CEO pay; that is up from 366-to-1 in 2020 and a big increase from 20-to-1 in 1965 and 59-to-1 in 1989.”18

-

Humble leadership style. Empowerment, autonomy, decentralized decision-making, and consultation with employees were typical.

-

Humble philanthropy. These entrepreneurs often made anonymous and substantial contributions to entities like the Cary Academy, the Downtown Project, and the Marine Corps Scholarship Foundation. They focused their philanthropic efforts on “lesser” organizations and on social welfare projects such as disaster relief.19,20

-

Impeccable business practices. The number of humble entrepreneurs involved in dysfunctional behavior was zero of 24, in contrast to dysfunctional behavior rate of destructive narcissists and destructive entrepreneurs (10 of 13).

-

People-oriented organizational practices. Sinegal’s business strategy was to take care of the employees so the employees would take care of the customers.21 Goodnight cofounded SAS Institute in 1976. SAS campuses include vacation and volunteer time off, unlimited sick leave, a free healthcare center, subsidized childcare, subsidized cafes, a fitness center, and a hair salon.22

-

Global impact. Humble entrepreneurs have created longstanding, successful global companies, such as Costco, SAS Institute, Chobani, FedEx, and Whole Foods.

-

-

Productive narcissists (high humility, high narcissism, non-entrepreneurs) — non-founders who paradoxically combined humility and narcissism, such as Eric Schmidt (Google), Lloyd Blankfein (Goldman Sachs), Tim Armstrong (AOL), Marcelo Claure (Softbank), Mike Armstrong (AT&T), Jack Welch (General Electric), John Chambers (Cisco), and Tim Cook (Apple). These CEOs shared narcissists’ grandiosity (mansions, yachts, private jets, media), but only three of 11 had been implicated in dysfunctional behavior. They have appeared in accounts of best CEOs.23,24

-

Paradoxical entrepreneurs (high humility, high narcissism, entrepreneurs) — founders who paradoxically combined humility and narcissism. Five characteristics identify them:

-

Extravagant lifestyle. Paradoxical narcissists displayed an astounding level of material wealth: yachts and super yachts, mansions and mega-mansions, private jets, private islands, “movie-star lifestyle,” luxury items such as Rolex watches and Armani suits, and private art collections.

-

Astronomical compensation. These CEOs received stunning annual total compensations. Former Oracle CEO Larry Ellison earned $1.84 billion over the course of a decade.25

-

Prestige-focused philanthropy. Philanthropy included self-named foundations (Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Chan Zuckerberg Initiative) and donations to prestigious organizations such as universities (endowments, named buildings, endowed professorships), hospitals, and medical schools. Prestigious organizations have developed a symbiotic relationship with narcissists. Harvard offered to rename its medical school for $1 billion.26 A prestigious art museum lists prominent donors prominently in the front lobby, famous works of art are usually displayed with the name of the donor, and galleries may be named for patrons. Anonymous rarely makes an appearance in an art museum.

-

Questionable business practices. Sixteen of 26 paradoxical entrepreneurs in the sample had been implicated on US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) fraud charges, racketeering lawsuits, accounting fraud, insider-trading accusations, bribery charges, toxic work culture, sexual affairs, a sexual harassment cover-up, and a variety of other scandals. Paradoxical entrepreneurs differed from destructive narcissists in two regards: (1) none had been responsible for the bankruptcy or demise of their organization, and (2) none had served time in prison for business crimes.

-

Global impact. Paradoxical entrepreneurs have transformed the world. In 2022, the so-called FAANG companies (Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Netflix, and Google) had a combined market cap of $7 trillion and constituted 19% of the S&P 500.27 Paradoxical entrepreneurs (co)founded and led all five of the FAANG companies (Facebook/Zuckerberg, Amazon/Bezos, Apple/Jobs, Netflix/Hastings, Google/Brin). Other paradoxical entrepreneurs included Elon Musk (Tesla, SpaceX), Michael Dell (Dell), Steve Case (AOL), Ralph Lauren (Ralph Lauren Corporation), Mark Cuban (Mavericks), Rupert Murdoch (News Corp), Pierre Omidyar (eBay), Herb Kelleher (Southwest Airlines), Howard Schultz (Starbucks), Bill Gates (Microsoft), Richard Branson (Virgin Group), and Ellison (Oracle).

-

Conclusion

This article explored the behavior and consequences of leader humility and narcissism.

Humility has a profound positive impact on leader behavior and firm competitive advantage. Humble CEOs and humble entrepreneurs exhibit a modest lifestyle, relatively modest compensation, humble leadership style, humble philanthropy, impeccable business practices, people-oriented organizational practices, and global impact.

Narcissism in the absence of humility leads to dysfunctional leader behavior and firm disadvantage. There is some debate about the effectiveness of narcissistic leaders. One view is that narcissists constitute a single group. They are either productive, destructive, or perhaps both simultaneously or sequentially. Michael Maccoby viewed narcissists as a single set of leaders with positive and negative potential, the “incredible pros,” and the “inevitable cons.”28 These arguments rest on the fallacious assumption that there is a single type of narcissist. It is much more likely that there are several homogeneous and predictable groups of narcissists. Humility together with narcissism has a profound and complex impact on leader behavior and firm competitive advantage. Paradoxical entrepreneurs (and, to a lesser extent, productive narcissists) exhibit extravagant lifestyles, astronomical compensation, prestige-focused philanthropy, and questionable business practices. They differ from the classical narcissist such as Lay in two ways. Humility is associated with a dramatically reduced frequency and severity of dysfunctional behavior among high-humility narcissist groups compared with identical low-humility narcissists. Most significantly, Jobs and his peers have created advanced, technology-based companies that have transformed the world.

This study provides an answer to the mystery of Jobs. He was not a solitary genius but a member of a large fraternity of powerful innovators who combined narcissism and humility.

References

1 Hyman, Jeff. “Why Humble Leaders Make the Best Leaders.” Forbes, 31 October 2018.

2 Cazentre, Don. “Founder of Upstate NY Yogurt Giant Chobani Donates $2 Million to Turkish Earthquake Relief.” Syracuse.com, 10 February 2023.

3 Ignatius, Adi. “Chobani Founder Hamdi Ulukaya on the Journey from Abandoned Factory to Yogurt Powerhouse.” Harvard Business Review, 25 April 2022.

4 Grant, Adam. “Tapping into the Power of Humble Narcissism.” Ideas.TED.com, 14 March 2018.

5 Owens, Bradley. “Tapping the Surprising Science of ‘Humble Narcissism.’” Fast Company, 30 July 2018.

6 Moyer, Justin Wm. “Humble Narcissists Like Steve Jobs Make Best Business Leaders, Study Says.” The Washington Post, 27 March 2015.

7 Yarrow, Jay. “Here’s Why Steve Jobs Wore a Black Turtleneck and Jeans Every Day.” Business Insider, 11 October 2011.

8 Love, Dylan. “16 Examples of Steve Jobs Being a Huge Jerk.” Business Insider, 25 October 2011.

9 Press, Gil. “Apple and Steve Jobs Steal from Xerox to Battle Big Brother IBM.” Forbes,

15 January 2017.

10 Kaufman, Alexander C. “How Steve Jobs Became a Better Boss When He Curbed His Narcissism.” Inc., 27 March 2015.

11 Chatterjee, Arijit, and Donald C. Hambrick. “It’s All About Me: Narcissistic Chief Executive Officers and Their Effects on Company Strategy and Performance.” Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 52, No. 3, September 2007.

12 Neuendorf, Kimberly A. The Content Analysis Guidebook. SAGE Publications, 2001.

13 Pontrefract, Dan. “Former CEO Alan Mulally Is Who CEOs Need to Be Today.” Forbes, 11 July 2022.

14 Porath, Christine, and Douglas R. Conant. “The Key to Campbell Soup’s Turnaround? Civility.” Harvard Business Review, 5 October 2017.

15 Rogers, Taylor Nicole. “Meet Costco’s Multimillionaire Cofounder Jim Sinegal, a Democrat Megadonor Who Was Only Paid a Third of the Average CEO’s Salary During His Time Leading the Wholesale Retailer.” Business Insider, 16 September 2020.

16 “Costco CEO Finds Pro-Worker Means Profitability.” ABC News, 1 December 2005.

17 “Jim Sinegal Net Worth $500 Million.” Celebrity Net Worth, accessed January 2024.

18 Bivens, Josh, and Jori Kandra. “CEO Pay Has Skyrocketed 1,460% Since 1978.” Economic Policy Institute, 4 October 2022.

19 Jacobs, Gina. “Alumni Pledge $2.5M to Scholarships.” San Diego State University,

9 May 2011.

20 Cazentre (see 2).

21 ABC News (see 16).

22 Grube, Alyssa. “Our SAS Culture Code: Perks + Benefits.” SAS Life, 18 November 2019.

23 Maccoby, Michael. “Narcissistic Leaders: The Incredible Pros, the Inevitable Cons.” Harvard Business Review, January 2004.

24 Fernández-Aráoz, Claudio. “Jack Welch’s Approach to Leadership.” Harvard Business Review, 3 March 2020.

25 So, Jimmy. “Oracle’s Larry Ellison: Best Paid CEO of Decade.” CBS News, 27 July 2010.

26 Herszenhorn, Miles J., and Claire Yuan. “Want to Rename Harvard Medical School? The Price Is $1 Billion.” The Harvard Crimson, 21 September 2023.

27 Fernando, Jason. “FAANG Stocks: Definition and Companies Involved.” Investopedia,

24 September 2023.

28 Maccoby (see 23).