AMPLIFY VOL. 36, NO. 12

Muhammed Shaahid Cassim and Fatima Hamdulay explore the concept of heartfelt leadership through the lens of the Islamic Sufi tradition, focusing on tasawwuf, the science of character excellence. Grounded in the belief that the heart is the seat of emotion, spirit, and morality, the authors delve into the Sufi perspective on good character and its role in leadership. They emphasize three considerations (intentionality, entrustment, and sincerity) that govern the heart and its decision-making.

Indeed, there is a part of the body that, if sound, the whole body is sound, and, if corrupt, the whole body is corrupt: indeed, it is the heart.

— the Prophet Muhammad ﷺ1

The heart occupies more than just a protected chamber in the human body — it is at the center of past and present communities and their traditions. We speak of enjoying experiences wholeheartedly, of loving with all our heart, and of hearts that race, soar, ache, and break. We admire those who bring “heart” to a team and teams “with heart.” We bemoan those who are “hard of heart” or a team that lacks “real heart.”

Much of what we intuitively experience of heartfelt living is easy to recognize but hard to explain with clinical precision. Still, we know with certainty that matters of the heart are not trivial. Beyond the biological heartbeat governing the mechanics of life itself, we know the heart as the seat of emotion and spirit, where trust is earned or lost, where pacts are made or fall apart, and where care and compassion compete with neglect and indifference. What, then, does it mean to lead with the heart, and what is the character of heartfelt leadership?

To answer this question, we draw on the Islamic Sufi tradition. Among the many belief systems of the world accepting the heart as the central hub of spirituality and meaning, Islam, and the Sufis within them, is one of the few where it is still alive.

Muslim Sufis position the heart as central to achieving excellence in the human endeavor we call life. With an expansive legacy traceable to the early 7th century, theirs is an enduring legacy of knowledge and experiential learning passed from master to disciple for more than 1,400 years.

During this period, Sufi masters contributed many influential works on tasawwuf, the science of character excellence. Sufi authors with reputations as genius-level experts in the field include Al-Qushayri, Al-Ghazali, Ibn Arabi, and Rumi. Some have referred to these authors as “mystics” or “romantics.” In fact, they were Muslim scholars drawing on the Qur’an and the prophetic tradition. References to “mystical” representations are largely informed by poor translations and selective readings of original works.2 For grounded insight about leading and character in this tradition, an objective, culturally appreciative analysis of tasawwuf is required.

Tasawwuf: Governing Toward Good Character

Practitioners of tasawwuf (the Sufis) are people within the Islamic tradition with especially pragmatic concerns for improving character. There’s a well-known Sufi adage, ascribed to Al-Kinani: “Tasawwuf is good character, and whoever excels in good character excels in tasawwuf.”3

For the Sufi, improving one’s character involves achieving spiritually imbued excellence in all aspects of one’s life (ihsan). This pursuit of spiritually imbued excellence through good character gave shape to tasawwuf as the science of character excellence. In the Islamic Sufi tradition, purification of the heart through tasawwuf is crucial to good governance and leadership.

Tasawwuf emphasizes holistic self-governance solutions incorporating all aspects of the human being: body, mind, self, and heart.4Body represents a person’s physical nature informed by diet, rest, exercise, and so forth. Mind is a person’s mental and intellectual nature informed by language, learning, and knowledge. Self is a person’s self-concept and identity informed by sociocultural and other influences. Heart is a person’s emotional and spiritual core guiding decision-making and action.

To explain the interrelatedness of the heart with the other aspects of our being, Andalusian Sufi master Ibn Arabi describes the heart’s role as the seat of power. Mirroring leadership structures of his time, he calls it “the castle from wherein the soul rules.”5

As justification for this powerful positioning, Ibn Arabi refers to a narration (hadith) of the Prophet Muhammadﷺ: “Indeed, Allah (God) does not look at your bodies or outward forms; rather, He looks at your hearts.”6 In other words, the test of the true quality of one’s action lies within the heart. In Ibn Arabi’s work, the role of the heart as a key determinant of human action is further heightened by it being positioned as the source of fortitude, will, and resolve.

In Sufi thought, the heart has the moral intelligence to distinguish between right and wrong (in Sufi parlance, to differentiate the praiseworthy from the blameworthy). As such, the heart can be a site of corruption or of reformation toward ihsan (spiritually imbued excellence) and must be safeguarded from the oppression of crimes against oneself and others.

The heart must also be safeguarded from excesses of desires and attention seeking, as these obscure its ability to envision correct action (that which is pleasing to God). In positioning the purification of the heart as fundamental to character excellence, the Islamic Sufi tradition perceives good-heartedness and good character as synonymous.

This emphasis on character excellence is further established through two prophetic pieces of advice:7

-

Nothing weighs heavier on the scale than good character.

-

The prophetic mission was centered on refining character.

How does this view of the heart (as a seat of power; a site of moral intelligence, fortitude, will, and resolve; and a site for goodness or corruption) inform how we think about what it means to lead?

3 Considerations That Govern the Heart

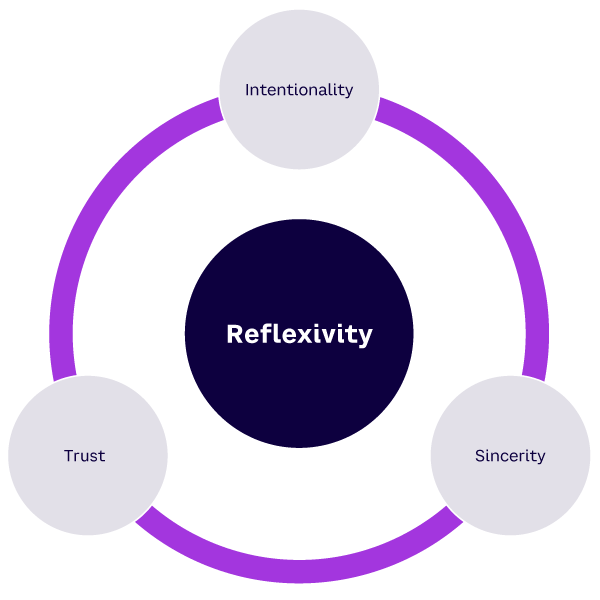

In linking good-heartedness and good character to the governance of good action, the Sufis typically raise three considerations that govern the heart, its decision-making, and what it means to lead (see Figure 1).

1. Intentionality

The first is intentionality, which refers to being deliberate and purposive in one’s thoughts and actions. Islamic Sufi tradition invokes a widely used prophetic narration directing scrutiny of one’s intent: “Every deed is judged by its intention.”8 For the Sufi, this intention is about an enduring and persistent consciousness of purpose. With the heart as the seat of true purpose, deeds are judged by what is present within the heart (or, more simply, what the heart desires). The truest intent and purpose of an action, and consciousness of that purpose, lie within the heart.

From a Sufi perspective, leading from the heart is about acting intentionally and with consciousness of purpose. It seeks to include and move beyond the long-term vision of purpose common in leadership speak today, emboldening each moment of engagement with the world (and the souls that inhabit it) with the intention of doing good for both the here and now and the ever after.

Seen in this way, intentionality armors the heart with temperance and forbearance when expediency might threaten to take hold. It also fosters resolve in the face of hardship and compassion and care when anger might easily rule in a moment of weakness. It regulates and directs character to what is healthier in the moment, in light of a grander purpose.

2. Trust

In Sufi tradition, leadership is not a station afforded to one by power or authority. Rather, it is the heart’s acknowledgement that as carrier and proxy of a divine trust, it is indebted to others to deliver on this trust (i.e., we are not entitled to followership).

This is very different from the dynamics that play out, consciously and unconsciously, in the dark recesses of organizational life. Operating from a place of indebtedness imbues the heart with humility and care. It asks us to acknowledge that in as much as we have governing responsibilities for the condition of our own hearts, we also carry a trust and power over the hearts of others. We owe them, and their hearts, a trust.

In this indebtedness, we are able to invoke our service ethic and spur cultures of clear commitment, rather than callous compliance. When entrustment lives in the heart, and our indebtedness is activated, we genuinely care about the purpose we espouse and those we seek to bring along on a journey of goodness.

3. Sincerity

The third heart-based consideration for leading is an aspect of character excellence called ikhlas (sincerity). This is the component that brings heartfelt leadership to the fore. Sincerity tempers the ego and brings to life intentionality and trust. One scholar of tasawwuf was asked: “What is the most severe thing upon the ego? “Sincerity,” he replied, “because the ego has no portion in it.”9

Sincerity cannot easily be measured, but insincere leadership is inherently felt. Insincere leadership manifests as ego-driven desires such as selfishness, praise seeking, and indifference toward others. Sincere desire for collective thriving, on the other hand, shows up as care and concerted effort in the greater good. It seeks praiseworthy action but does not covet the praise. It touches hearts and encourages lofty purpose. It shows up as unwavering dedication in times of need and going the extra mile when no reward is expected. As one Sufi scholar put it: “Actions are lifeless forms, but their spirit is the presence of sincerity within them.”10

These three considerations require a unifying practice to make them work coherently. This practice is muhasabah (reflexivity). Muhasabah literally means calling one’s self to account by holding one’s thoughts, assumptions, feelings, and actions up to scrutiny, against the lens of delivering on trust and indebtedness, all while questioning one’s sincerity and motives and thinking about intentionality. It means: (1) taking ownership of our shortcomings and not deflecting bad outcomes to followers or others and (2) leading from within so that others may shine.

Heartfelt leadership grounded in reflexivity is a call to be intentional and sincere about the trust placed in us by our followers. It means working to lead from a locus of care and compassion while maintaining equity and justice. It activates relational trust and care and enlivens the spirit and hearts of those it touches. It requires frequent pauses to reflect; regular stock taking, cleansing, and review; and periodic renewals of intentionality. Heartfelt leadership is more than a change of mindset. It is a change of heart.

Activating Heartfelt Leadership

If the heart brings leadership to life, how does one bring hearts to life? Tasawwuf has a view on this. As a character development system directed to the divine, its recourse for the heart is to connect to the divine. And one of the easiest ways to do that is to serve, not lead.11 We see this in many examples of CEOs working “undercover” as staff members to better understand organizational workings from the perspective of their staff.12 But serving from the heart is more than this. It involves paying close attention to how we show up, moment to moment, day to day, and week to week, through our tenure. It means taking stock of ourselves and our organizations. It means being genuinely attentive to the people we serve and caring for them more than we care for ourselves. It means finding ways to be more heart-led.

Heartfelt leadership requires directing action to what is praiseworthy — but not for the sake of praise. When the heart accompanies leadership, actions are heartfelt by doer and receiver, leader and follower. Trust follows because one is leading from the castle where care resides, compassion thrives, and equity and justice are subject to morally informed reason.

When leadership is heartfelt, people feel cared for, challenged, safe, and willing to themselves lead from the heart. When it is not heartfelt, leadership becomes cold and calculating, self-serving and callous. There is little trust, and true heart (which we so admire and covet) is hard to find.

Ask the Right Questions

To build heartfelt leadership, we must determine whether or not we show up in ways that manifest the character of heartfelt leadership as described above and answer with unrivaled internal honesty. Ask the following:

-

Why I am doing this? Whom do I serve?

-

Does my purpose stretch beyond me to include all of my people and something beyond us?

-

How will I live this purpose today?

-

Do I operate from a place of entitlement or indebtedness?

-

Am I demonstrating real care toward my people? How will I know?

-

Do I care more for my people or for myself? How will I know?

-

In challenging times, is my intended action praiseworthy? What is my real intent? What does my heart hope to gain here? Is it aligned with my larger purpose?

-

Are my actions genuinely heartfelt or are they bereft of heart?

Similarly, the organizational culture and the nature of followers are like an echo chamber. The castle sets the tone for the town. Ask:

-

Do my people seem well-cared for?

-

Are my people’s actions heartfelt and sincere?

-

Do they go the extra mile even when no one is looking?

-

Do I see entitlement in them or indebtedness?

-

Do I sense deep commitment or heartless compliance?

-

Do my customers and clients rave about how great my employees are?

The outcome of this scrutiny should reveal the true character of our leadership and our organizations. In heartfelt leadership, if the heart is sound, the body is sound, and the test of our character lies in how we respond in moments of truth. If what we see in ourselves and our organizations seems less than sound, the heart needs reformation and intervention. And rather than prescribe what this intervention should be, consult your heart. The last time a leader touched your heart, what is it they did? What was the character of that action? If you could emulate that action, what would it look like?

To change the heart, do something from your heart for those you lead. We could all do with a little more heart, a little more care, a little less entitlement, and little more indebtedness as we deliver on our divine trusts.

References

1 A narration (hadith) from the corpus of sayings of the Prophet Muhammad ﷺ; see: Al-Hajjaj, Muslim ibn. Sahih Muslim, book 22, hadith 133.

2 See, for example: Lipton, Gregory A. Rethinking ibn ‘Arabi. Oxford University Press, 2018.

3 Al-Ghazali, Abu Hamid. Ihyh Ulum al-Din (Revival of the Religion’s Sciences). Dar Al-Kotob Al-Ilmiyyah, 2011.

4 The use of “self-governance” was inspired by Amin Abdul Aziz‘s rendition of an Islamic system of governance. While self-governance per se is not a focus of this article, Aziz’s ideas on governance as a system, inspired by what he calls the “Prophetic Madinian Polity,” are important to the discussion. For more on Aziz’s thoughts on self-governance, see: Azziz, Amin Abdul. “Of Leaders and Leadership.” The Journal of Islamic Governance, Thought Paper No. 1, August 2020; Aziz, Amin Abdul. “Governance in a Contemporary Islamic Negara.” The Journal of Islamic Governance, Vol. 1, No. 1, November 2015; and Shamdi, Wafi, et al. “Artificial Intelligence Development in Islamic System of Governance: A Literature Review.” Contemporary Islam, Vol. 16, November 2022.

5 Arabi, Ibn. Al-Tadbirat al-Ilahiyyah fi Islah al- Mamlakat al-Insaniyyah (Divine Governance for the Reformation of the Human Kingdom). Dar Al-Kotob Al-Ilmiyyah, 2003.

6 Al-Hajjaj, Muslim ibn. Sahih Muslim, book 1, hadith 7; and Al-Nawawi, Yahya ibn Sharaf. Riyad al-Salihin English Translation & Commentary. Muslims at Work (South Africa), 2014.

7 At-Tirmidhi, Abu Isa Muhammad. Jami at-Tirmidhi, hadith 2003 and hadith 1162; Anas, Malik ibn. Muwatta Malik, hadith 1643.

8 The term “niyyah” has been translated here as “consciousness of purpose” instead of “intention,” since consciousness of purpose better reflects the meaning of niyyah in comparison with the vaguer word, “intention”; see: Al-Nawawi, Yahya ibn Sharaf. Riyadh al-Salihin (Gardens for Righteous), chapter 1, hadith 1.

9 Al-Qushayri, Abu ‘l-Qasim. Al-Qushayri’s Epistle on Sufism. Garnet Publishing, 2007.

10 Al-Qadir Isa, Shaykh Abd. Realities of Sufism. Sunni Publications, 2009.

11 This is, of course, not the only way. As Muslims, Sufis pay close attention to fulfilling all their religious and interpersonal obligations, with the aim of earning God’s pleasure within the moral framework of Islam. Within this moral framework, the way of service comes from a prophetic narration: Al-Nawawi, Yahya ibn Sharaf. Riyadh al-Salihin (Gardens for Righteous), hadith 896.

12 See, for example, the television series Undercover Boss. The novelty of the show is a reminder of the power and counter-narrative nature of serving in this manner.