Executives spend a lot of time strategizing about how to enter and grow their business in emerging economies. But what happens when the wind changes and stakeholders at home no longer support such international expansion, instead creating obstacles — from nongovernmental organization (NGOs) campaigning against alleged human rights abuses to governments imposing sanctions on countries deemed hostile to national interests? A decision to leave a foreign country requires complex financial, operational, and ethical considerations. First, the financial analysis of the operation under scrutiny must be adjusted to account for losses incurred elsewhere in the global organization. This Advisor takes a closer look at this initial step, using Russia as an example.

Financial Analysis

Let’s start with an accounting perspective. The moment a major political disruption occurs, the market value of a multinationals’ operation in the affected country collapses. In the case of Russia, this happened to the Western subsidiaries based there on 24 February 2022. Such a disruption typically leads to a drop in demand, cost increases, and a rise in economic and political risks. Moreover, potential buyers’ willingness to pay for the firm’s business unit declines sharply, especially if they are constrained by sanctions from their own governments. Western investors do not want to put fresh money into Russia, local buyers outside the energy sector lack financial resources, and third-country buyers often play a waiting game.

Thus, historical investment costs are sunk costs, and the book value in accounts is not the relevant benchmark. This is important to consider because the financial analysis of any exit strategy must be assessed against the next best option. The relevant baseline is the net present value (NPV) of the operation (if that’s the performance indicator on which you focus) based on the revenue and cost projections at the time (i.e., after the disruption).

Understanding Resource Dependencies

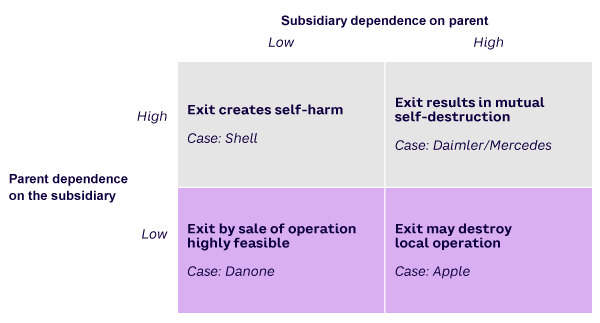

Executives must also consider the interdependence of affected subsidiaries with the rest of their company’s global operations. Multinationals typically operate highly integrated operations that span national boundaries, with regular exchanges of goods, people, and knowledge across borders. Thus, a decision to exit from one country typically has implications for the entire operation. These interdependencies are not always obvious or straightforward. Figure 1 considers four scenarios.

The simplest scenario is that of a largely autonomous subsidiary with limited product or technology exchange with other units of the enterprise (bottom-left quadrant, Figure 1). Pure diversification investments fall in this category, as do hospitality businesses like restaurants or hotel chains.

Consider French manufacturer Danone, which has been producing in Russia since 1994. In 2021, Danone was the largest milk processor in the country with 13 factories. Its business model relied mainly on local supply chains and most sales were under local rather than global brand names. These product lines could be sold off to a local investor.

But Danone used global brand names (e.g., Actimel and Activa) for some products and imported specialized ingredients for others. When Danone sold its Russian operation to a local investor, a critical question was whether Danone would allow the new owners to continue using its global brand names.

Operations that primarily serve the local market are often dependent on ongoing parent contributions in the form of specialized components or even finished products (bottom-right quadrant, Figure 1). Such operations are easily shut down by cutting off supplies. In contrast, distribution operations are not self-standing businesses and may not be able to be sold as “going concern.”

Consider Apple, the leading provider of iPhones and other appliances, competing in 2021 with Huawei and Samsung to be the number one smartphone brand in the country. Apple’s Russia operations were primarily market-oriented: selling iPhones and iPads via authorized resellers. It cut off Russia by halting product shipments in March 2022. Resellers thus had to shut down unless they had access to grey imports via third countries. This resulted in a substantial drop of revenues; press estimates suggested losses of sales of US $1.4 billion per year. Since Apple did not own its stores, an asset sale was not required.

Nevertheless, things proved complicated for Apple. Its devices are in circulation in Russia, and past buyers bought them with the expectation that software would be updated regularly and that the Apple App store would be readily available. Would Apple renege on the (implicit) promise it gave to customers? In fact, it only did so partially. Apple restricted the functionality of Apple Pay (in response to sanctions on financial transfers) and removed various apps of sanctioned Russian businesses from its smartphones.

Operations such as mining or upstream manufacturing usually create a dependence of the parent on the subsidiary (top-left quadrant, Figure 1). A disruption in a vertically integrated supply chain may severely undermine downstream operations. For mining operations, buyers are likely available because of the value of the resources in the ground, though they may face limitations if they do not have access to critical extraction technology.

For multinationals, the greater concern may be the disruption of the relationship with the subsidiary causing substantial harm to the parent. For example, Shell owned equity stakes in several oil and gas exploration projects, usually partnering with state-owned Russian businesses. Interdependencies arose from its network of local equity partners, which restricted the available options when Shell wanted to sell its equity stakes. Shell stopped all spot purchases of Russian gas and refined products and has not renewed any long-term contracts, but it was still legally obliged to take delivery of crude bought under contracts signed before the invasion.

In global supply chains like the automotive industry, dependencies in the value chain are often complex and mutual. Components are produced in specialized (internal or external) suppliers in some countries, from where they are shipped to assembly plants across Europe. Assembly plants specialize in certain car types and export the finished car to a third country, or even back to the headquarter country. Thus, components and technology flow both in and out of the country.

Consider Mercedes, which invested in a state-of-the-art passenger-car assembly line in Russia that began operating in 2019. This new production site increased Mercedes presence in Russia, despite sanctions in place since 2014. In 2022, Mercedes stopped exports of cars and vans and ceased local production, in part because new sanctions prohibited exports of high-tech components. Mercedes sold its shares in its distribution network, production plant, and joint ventures to Avtodom, a Russian dealership chain.

An interdependencies analysis must include the impact of costs and revenues of the global operation. Hence, the relevant NPV is not that of the subsidiary but that of the global operation. To inform an exit decision, the subsidiary NPV must be adjusted for losses in the NPV for the rest of the global organizations. In some cases, such losses can be mitigated by developing an alternative supply chain, but the resulting delays may prolong the presence of the controversial business unit.

We would like to thank Anna Tiunova for her effective research assistance.

[For more from the authors on this topic, see: “Managing Exit Strategies: Lessons from Russia.”]