AMPLIFY VOL. 38, NO. 4

Despite growing recognition of firm complexity’s influence on business development, little is known about what drives firm complexity itself.1 CEOs influence how organizations are structured, yet the impact of their traits on firm complexity is not well understood. Given that CEO overconfidence influences risk-taking and decision-making, it may also play a role in shaping firm complexity, greatly affecting organizational efficiency and adaptability.

Firm complexity is an omnibus construct encompassing multiple dimensions, including operational, structural, and strategic intricacies.2 Although a certain level of complexity can drive innovation, facilitate expansion, and enhance competitiveness, excessive complexity tends to hinder decision-making, increase costs, and reduce transparency for investors.

However, excessive complexity reduction can weaken essential structures, limiting a firm’s ability to compete effectively in dynamic or highly regulated markets. Striking the right balance is essential.

CEOs shape firm complexity through their strategic decisions and managerial choices.3 Overconfidence (a common trait among CEOs) leads them to overestimate their abilities while underestimating risks.4 This tendency drives substantial changes in firm complexity by influencing investments and financing.5

Interestingly, despite its impact on corporate decision-making, the relationship between CEO overconfidence and firm complexity remains an underexplored issue.

Why Firm Complexity Matters

Firm complexity isn’t just a buzzword, it’s a double-edged sword for business. Some complexity, like diverse product lines or global operations, can spark innovation and provide a competitive edge.6 However, excessive complexity hinders operational efficiency, inflates costs, and erodes investor confidence in financial reporting.7

Striking the right balance is crucial, but when CEOs are overconfident, they tend to either oversimplify or overcomplicate matters, potentially disrupting a firm’s strategy and performance.

Drawing on more than 14,564 firm-year observations from 2002 to 2023, we analyzed earnings conference call (ECC) transcripts to explore the impact of CEO overconfidence on firm complexity. This article describes our findings, explores what they mean for businesses, and offers clear, actionable steps to achieve balance.

Our Approach

ECCs are a critical communications channel between corporate executives and investors, offering insights into firm performance, strategic initiatives, and future outlook. Typically, ECCs consist of a presentation, where executives share prepared remarks; a Q&A, where analysts and investors ask questions and executives respond; and a full transcript combining both. Analyzing them provides insight into how CEOs shape their presentations and gives us a way to assess the degree of firm complexity embedded in these discussions.

To measure firm complexity, we used a textual dictionary approach to analyze our data, which was pulled from multiple industries to ensure our findings reflect broader corporate trends rather than being limited to specific sectors. We aimed to capture firm complexity holistically and dynamically, moving beyond linguistic complexity to incorporate structural, operational, and strategic dimensions.

This approach, based on the omnibus firm complexity measure developed by Tim Loughran and Bill McDonald, ensures a comprehensive assessment of complexity, making it relevant for corporate boards, investors, and policymakers.8

By examining the frequency (how often) and patterns (how they appear) of complexity-related terminology used in ECC transcripts, we tracked the ways firm complexity evolved over time and varied across sectors. This enabled a deep understanding of how corporate decision-making, regulatory pressures, and market conditions shape a firm’s overall complexity over time.

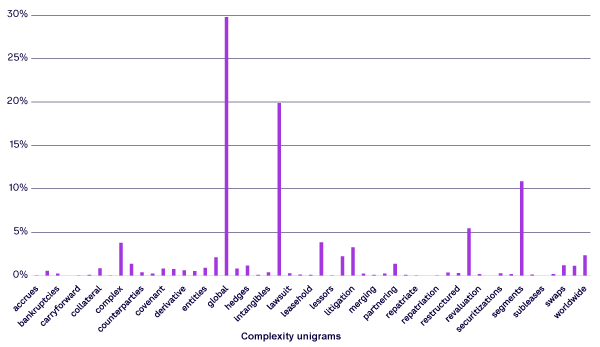

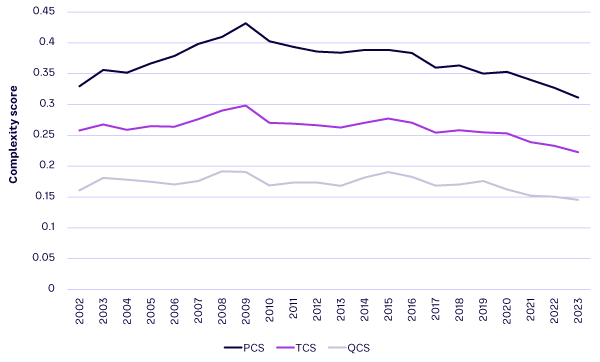

Figure 1 (a word cloud) and Figure 2 (a frequency chart) illustrate how often complexity-related terms are employed, highlighting the extent to which firms discuss complex organizational structures, operations, or strategies during their earnings calls. We created three complexity scores:

-

Presentation complexity score (PCS) — the level of complexity reflected in a firm’s structured, high-level strategy discussions in the presentation

-

Question and answer complexity score (QCS) — the depth of firm-specific operational and strategic challenges revealed during the Q&A

-

Total complexity score (TCS) — a holistic measure of firm complexity achieved by combining the two scores above

Figure 3 shows a gradual decline in complexity, particularly after 2010, suggesting a shift toward reduced firm complexity. This trend aligns with our findings (described below) that overconfident CEOs tend to reduce firm complexity. The reduction may reflect attempts to streamline operations and decision-making, but it raises concerns about whether vital details and oversight structures are being diluted in the process.

Overconfidence Identification

To identify overconfident CEOs, we employed a systematic, empirically grounded approach based on prior literature. We followed Ulrike Malmendier and Geoffrey Tate’s methodology, which measures overconfidence by looking at a CEO’s tendency to retain unexercised stock options that are “in the money,” a behavior interpreted as excessive optimism about future firm performance.9,10 Data for this measure was sourced from ExecuComp, which provides detailed executive-level compensation information necessary for calculating stock option holdings.

This measure of overconfidence has been widely validated and offers a reliable indicator of psychological traits. To enhance robustness, we applied industry-fixed effects to account for unobservable sector-specific characteristics that may affect firm complexity or executive behavior. By integrating a well-established behavioral proxy with rigorous econometric controls, our analysis offers a strong empirical foundation for examining how overconfident CEOs influence the complexity of firm operations and strategic communication.

What We Discovered

Our findings reveal a consistent pattern: CEO overconfidence is associated with lower levels of firm complexity, as captured in ECC transcripts. The effect is economically meaningful; on average, firms led by overconfident CEOs exhibit 3.1% less complexity than those led by non-overconfident CEOs.

This reduction in firm complexity may indicate that overconfident CEOs intend to streamline operations and improve efficiency. However, it should also raise concerns. Oversimplification can weaken internal oversight and/or reduce the organization’s capacity to manage diverse operations effectively. Boards and investors should exercise caution in interpreting a reduction in complexity as unequivocally positive. It may reflect underlying inefficiencies or oversights in internal decision-making processes that warrant further examination.

To contextualize these patterns, we examined variations across firm and CEO characteristics in our study:

-

The average CEO age is 52, with an age range from 30 to 78, reflecting diverse leadership experiences.

-

Approximately 32% of CEOs in our sample are classified as overconfident, based on established behavioral measures using ExecuComp data.

-

The firms in our study differ substantially. The firm size (total assets) ranges from US $57.9 million to $482 billion. A wide range of market-to-book ratios (from 0.6 to more than 14) suggests that our sample includes a diverse set of firms, from mature, value-driven companies to high-growth firms that attract strong investor interest. More than half (55%) of the firms prioritize returning value to shareholders through regular cash payouts (dividends). Only 5.4% of firms engage in R&D spending, suggesting that innovation is not uniformly distributed.

These differences underscore that firm complexity and leadership style are not “one size fits all.” Rather, they must align with the specific characteristics and strategic needs of each organization. The impact of CEO overconfidence on complexity should be interpreted in light of firm-specific contexts, such as age, size, industry, and strategic focus.

Practical Implications

With deeper insights into how CEO overconfidence affects firm complexity, corporate boards, executive leadership, and investors can better anticipate the level of complexity a firm may experience under various leadership styles.

Studies show that CEO overconfidence influences corporate decision-making, risk-taking, and investment strategies, which in turn shape the structural complexity of firms.11,12

For corporate boards, recognizing the impact of CEO traits on firm complexity can help board directors make informed decisions when selecting and appointing CEOs, ensuring that leadership aligns with the firm’s strategic needs and operational demands. A thorough understanding of CEO traits and their implications for firm complexity is essential for boards, especially during leadership transitions.

For example, during John Flannery’s short tenure at General Electric (GE), he initiated rapid divestitures and restructuring efforts intended to simplify GE’s operations and sharpen strategic focus. These actions, marked by decisiveness and confidence, suggest his approach may have been overconfident in nature. Analysts and insiders noted that the changes lacked long-term alignment with GE’s complex portfolio and operational structure. This led to investor uncertainty and insufficient performance recovery, resulting in Flannery stepping down after just 14 months as CEO.13 This example highlights that simplification driven by overconfidence (especially if not well aligned with the firm) can be ineffective and even destabilizing.

For executive leadership, balancing complexity management with resilience is crucial. Reducing complexity can streamline decision-making and enhance efficiency, but overly aggressive simplification may undermine innovation, governance structures, and adaptability. Research suggests firms that carefully manage complexity rather than eliminate it tend to achieve better long-term performance outcomes.14

For instance, Tim Cook’s leadership at Apple reflects a measured, disciplined approach. Unlike some executives who aggressively simplify firm structures without fully accounting for operational needs, Cook has maintained a focused product strategy while effectively managing complexity through robust systems and strong governance. Under his leadership, Apple streamlined its offerings (focusing on core products like the iPhone and Mac) while expanding into services, wearables, and global supply chains. This shows how confidence rooted in operational discipline, not overconfidence, can support both innovation and long-term adaptability. Cook’s inclusive, consensus-driven style has strengthened Apple’s governance, resilience, and performance.15

For investors, understanding the role of CEO traits in shaping complexity can provide early signals of risk and strategic direction. For example, a sudden reduction in complexity may indicate overconfident decision-making rather than a well-planned restructuring strategy. By analyzing complexity trends, investors can assess whether changes reflect a sustainable strategic shift or a deviation from sound management practices.

Ultimately, integrating CEO trait analysis into governance, leadership development, and investment decision-making can help firms achieve a sustainable balance between complexity and efficiency, ensuring long-term resilience and value creation.

A Balanced Strategy

A firm’s complexity is shaped by many factors, but one of the most overlooked is the personal traits of the CEO. Leadership style, cognitive biases, and decision-making tendencies directly impact how a firm structures its operations, manages risk, and navigates strategic challenges.

Among these traits, CEO overconfidence is particularly influential, as it drives bold, rapid decision-making that could streamline operations for efficiency or introduce unforeseen risks due to excessive simplification.

Although our study finds that overconfident CEOs often simplify firm structures, not all do. At WeWork, Adam Neumann’s overconfidence led to fast growth and expansion into unrelated areas, making the company more complex.16 This happened partly because there weren’t strong governance controls in place to ensure executives could question his decisions. This shows that the effect of overconfidence on complexity depends not just on the CEO’s actions, but also on how well the company’s leadership is supervised.

Recognizing how CEO traits shape complexity is essential for corporate boards, executives, and investors, as it enables them to anticipate shifts in firm structure, ensure strategic oversight, and avoid governance pitfalls associated with unchecked leadership tendencies. A well-balanced complexity management strategy must align with the firm’s long-term vision rather than be dictated by a CEO’s personal leadership style.

Overconfident CEOs often make swift decisions aimed at simplifying organizational structures. Rapid simplification can introduce several challenges, including increased exposure to risk, resistance from key stakeholders, and a lack of clear performance tracking. Overconfidence may lead executives to bypass critical due diligence processes when entering new markets or launching new products, resulting in costly miscalculations. Additionally, sudden reductions in complexity can trigger pushback from employees and investors, particularly if key operational processes or oversight mechanisms are eliminated.

In the absence of clear performance tracking, firms may struggle to assess how complexity shifts influence long-term sustainability, creating potential blind spots in governance and risk management.

Conclusion

Our findings reveal that overconfident CEOs are more likely to simplify their firms, often reducing complexity across multiple dimensions. However, whether this simplification is beneficial depends on the nature of the firm, its industry, and its strategic goals. In some contexts (e.g., fast-moving consumer goods or logistics), streamlining may enhance efficiency and responsiveness. In contrast, firms operating in innovation-driven sectors like technology or healthcare need to maintain a certain level of complexity for flexibility and long-term value creation.

Boards should not view reduced complexity as inherently positive or negative. Instead, they should interpret it through the lens of CEO traits. Overconfident CEOs may underestimate the need for oversight or ignore operational complexity.

Boards and investors should critically evaluate whether complexity reductions reflect thoughtful strategic design or an overconfident leader’s tendency to cut corners. Regular assessments of complexity, when paired with an understanding of executive personality, can make clear whether changes align with long-term resilience or risk eroding a firm’s adaptive capacity.

Full empirical analyses, variable definitions, and summary statistics are available from the authors upon request.

References

1 Loughran, Tim, and Bill McDonald. “Measuring Firm Complexity.” Journal of Financial & Quantitative Analysis, Vol. 59, No. 6, September 2024.

2 Loughran and McDonald (see 1).

3 Hambrick, Donald C., and Phyllis A. Mason. “Upper Echelons: The Organization as a Reflection of Its Top Managers.” Academy of Management Review, Vol. 9, No. 2, April 1984.

4 Malmendier, Ulrike, and Geoffrey Tate. “CEO Overconfidence and Corporate Investment.” The Journal of Finance, Vol. 60, No. 6, November 2005.

5 Malmendier and Tate (see 4).

6 Qian, Gongming, Lee Li, and Alan M. Rugman. “Liability of Country Foreignness and Liability of Regional Foreignness: Their Effects on Geographic Diversification and Firm Performance.” Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 44, May 2013.

7 Bushman, Robert M., Joseph D. Piotroski, and Abbie J. Smith. “What Determines Corporate Transparency?” Journal of Accounting Research, Vol. 42, No. 2, April 2004.

8 Loughran and McDonald (see 1).

9 Malmendier and Tate (see 4).

10 Malmendier, Ulrike, and Geoffrey Tate. “Who Makes Acquisitions? CEO Overconfidence and the Market’s Reaction.” Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 89, No. 1, July 2008.

11 Malmendier and Tate (see 4).

12 Coles, Jeffrey L., Naveen D. Daniel, and Lalitha Naveen. “Boards: Does One Size Fit All?” Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 87, No. 2, February 2008.

13 Gryta, Thomas, and David Benoit. “GE Ousts CEO John Flannery in Surprise Move After Missed Targets.” The Wall Street Journal, 1 October 2018.

14 Bloom, Nicholas, Raffaella Sadun, and John Van Reenen. “Does Product Market Competition Lead Firms to Decentralize?” American Economic Review, Vol. 100, No. 2, May 2010.

15 Yoffie, David B., and Eric Baldwin. “Apple Inc. in 2018.” Case study, Harvard Business School, 4 May 2018.

16 Zeitlin, Matthew. “Why WeWork Went Wrong.” The Guardian, 20 December 2019.