CUTTER BUSINESS TECHNOLOGY JOURNAL VOL. 33, NO. 10

Samin Saadat and Jim Brosseau take us into their workshops and their research. The authors provide meaningful context to describe the barriers to inclusion, such as the history of management and leadership, communication technologies, and the effects of addictive social media platforms. They offer practical steps for companies to include on their way to becoming a more transparent culture and also outline the costs companies will inevitably pay for failed attempts and a lack of inclusion.

Diversity to Inclusion

In a recent workshop, Jim (coauthor) was discussing diversity and inclusion, suggesting the value of having explicit conversations about how to work better as a team in a diverse environment:

“Oh, that theoretical stuff...,” one participant remarked.

“By ‘theoretical,’ do you mean that you have never experienced this on a real project?” Jim asked.

After a moment, the participant admitted that was indeed the case.

Both within the workplace and in society in general, we are witnessing an intense focus on diversity: the Black Lives Matter movement; the renaming of professional sports teams; “cancel culture” campaigns; a demand for more women in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) disciplines; and hiring practices geared to ensure that a business’s internal demographics more closely represent the demographics of the environment outside the business. On one hand, emphasis is placed on trying to find an appropriate balance across different forms of diversity within the workplace while, on the other hand, diversity can become a wedge driving us apart rather than bringing us together in some elements of society.

Diversity is easily measured, and we tend to create metrics based on easy measures rather than seeking out insightful and valuable measures. For example, we identify project success through the lens of “on time” and “on budget,” instead of determining whether we have delivered the value desired. Merely being able to quantify that our organizations are diverse in no way achieves the outcomes we seek; rather, we need to leverage and manage all forms of diversity to bring us to the point of appreciative inclusion in the workplace. Appreciative inclusion goes beyond mere tolerance of diversity to recognize that, when harnessed, diversity can dramatically improve creativity and innovation, improve employee well-being and retention, and truly differentiate the organization — making diversity a strategic advantage.

Having diversity is a stepping-stone in the process of effective workplace inclusion, not a conclusion. Moreover, diversity and inclusion are very distinct ideas, though often misinterpreted. Diversity is a measure of how widely a group differs along one or more continuums, such as race, gender, age, experience, title, or a large list of other qualifiers; it is a metric. Inclusion, in contrast, is a set of practices, behaviors, and attitudes that allows us to leverage these various forms of diversity to make the organization more effective, creative, and innovative, with a broader range of experience, knowledge, and perspectives from which to draw.

We believe there are critical elements to consider as we move toward greater inclusion.

Barriers to Inclusion

In our workshops, our first exercise is to have participants identify the core distinctions between their best and worst project experiences. The outcomes of this exercise have not changed in decades and do not differ between domains or organizational roles. The distinctions are always about aspects of human interaction: trust, respect, effective communication, shared goals, integrity, and a host of others.

Yet these participants are often surprised when we suggest that appreciative conversations within teams to explore diversity are possible and that such conversations intentionally craft a culture that builds behaviors to bring a group of individuals together as a team.

The history of management and leadership that began with the Industrial Revolution, aided and abetted by the philosophy ingrained into our educational system, have trained us from an early age to be compliant and to work within a hierarchy. This has become part of workplace culture, and, as is true of any culture, it requires effort to move beyond the position of “that’s the way we do things around here.”

Traditionally, little support has existed for practices to improve inclusion in the workplace. Hierarchical leadership practices and command-and-control behaviors rely on compliance to be effective, and guidance from, for example, the Project Management Institute (PMI) over the years has been process-centric, with passing statements suggesting the human element is important but with no guidance on how to achieve inclusion. In our experience, most Agile implementations, for example, despite stated principles leaning toward consideration of the human element, have been largely process-centric as well.

We believe we are in the midst of change with respect to inclusion, however; a change that will take years to progress through the stages of the diffusion of innovation curve.1 As with any significant shift, there are innovators and early adopters — shining examples of effective practices for inclusion in the workplace. Others, the laggards, will fight the shift ruthlessly, whether because of a perceived loss of power, inertia, or simply lack of awareness of the possibility of intentional intervention.

Today, there is a Canadian national standard for psychological health and safety in the workplace and an accompanying practice guide that provides guidance for organizations.2 The entire discipline of organizational development can now be more closely tied to ongoing operations rather than having a supporting role. The rising popularity of insights from people such as best-selling author Daniel Pink,3 researcher and professor Brené Brown,4 and Ted Talks-famed Simon Sinek5 are raising awareness of critical practices to increase inclusion, and the barriers to leveraging these ideas in the workplace are slowly falling. Indeed, it is expected that the next iteration of the PMI’s A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK Guide)6 will move from a phase-based perspective to one focused on principles that are far more aligned with inclusive team development.

Technology, Culture & Personal Security

Every day, we communicate globally through various communications technologies: email, social media, Internet, and apps. We have started to see the world as one transparent entity where differences appear not to matter as much as they did previously. It is fair to say that technology plays a significant role in increasing the amount of information to which we have access, often resulting in greater transparency. Despite these positive impacts of technology, however, one pressing question remains unanswered: does technology increase our capacity to absorb information wisely?

Familiarity gives us comfort, which is why we tend to seek out information that enhances our existing ideas and knowledge. Information providers frequently take advantage of this psychological tendency, or confirmation bias. Social media platforms are designed to selectively expose us to the type of information we are already seeking, reinforcing our preexisting views. As an example, we may hold a bias against a certain group of people; a quick perusal of specific social platforms easily finds information to validate our bias. Another example comes from news feeds, which are designed to share information tailored to our preferences and search habits. Information tailoring can create a false belief that everyone shares our opinions. Consequently, it becomes easy to believe that our false assumptions about certain groups are 100% validated and that everyone else also believes what we believe.

Many people use technology platforms as a way to surround themselves with others who share their beliefs, and many also use these technologies to project hostility toward those they perceive as different. Unfortunately, social media algorithms and the addictive nature of the platform have made such behaviors both easy and fast to execute.

In fact, for a user to gain popularity and followers (e.g., social media influencers), social media platforms incentivize sharing information that the majority of that user’s followers want to read or see. These eye-catching, popular posts often center around extreme differences and unusual behaviors — think clickbait articles — to capture viewers. As individuals who are exposed to such distorted information, we should apply strong critical thinking skills to ensure the information we consume does not create a warped view of reality.

In comparison, how often do we see articles about how people are similar to each other? About how there are no black-or-white distinctions? About how a certain group of people feel, act, and think differently based on values that are not evil or worthless? The answer is very, very seldom.

In our work with companies in creating transparency that allows them to cultivate intercultural learning and an inclusive decision-making culture, we implement a few important interventions before providing access to large amounts of information. These interventions include:

-

Creating mutual understanding among an organization’s members that they are responsible for handling such information wisely and critically

-

Establishing policies and procedures to ensure that no one uses the information to sabotage or harm anyone

-

Providing training on how decisions should be made using the information, considering each person will have different perspectives on the information

Moving beyond the organizational level, we believe that technology has created more transparency and more access to information at a global level. There is, however, room for improvement in learning how to take a critical approach to information, in fostering intercultural learning, and in creating a sense of responsibility to handle information intelligently. Human behavior remains similar to what it was before the existence of today’s technology; the technology has only made it faster and easier to scale our behaviors and enhance our existing challenged interpretations.

Current Costs of Lack of Inclusion

Even in the era of technology, no organization can successfully produce goods and services without its people. Production and development do not arise from the product itself but require people and their mental effort and knowledge. An organization’s goods are successful only if they can be integrated into the knowledge and culture of the market.

On one side, we have to ensure our solutions are tailored to the specific market they are designed to serve. And on the other side, we are solving a common problem for a diverse group of people with different mindsets. How are we going to make sure our solution addresses a common problem for a diverse market? Of particular note is that the greater an organization’s market share, the more diverse its market. Perhaps our solution meets the basic and universal needs of the market, but how can we ensure our solution responds to individual differences in the market? Individuals all come to the workforce with unique patterns of thinking, feeling, and behaviors they have learned over the years. Based on their individual experiences, they have built strong mental schemas to make sense of a complex world and create an image of reality.

Imagine a workforce where employees leave their individuality at the door to function only in the organization’s preferred homogeneous way. While this hypothetical organization is trying to grow its market share by providing more diverse solutions to its market, the organization’s diverse people leave their best selves and their distinctive uniqueness at home to play it safe. The people in this organization no longer represent the organization’s diverse target market, and the organization misses out on much hidden potential.

Now imagine a competitor company that creates an environment where its people feel safe to share their differences, make mistakes, challenge the status quo, and simply learn and grow. The best employees from the homogeneous organization — who never had a chance to flourish — may take their brilliant ideas to this competitor, which then successfully captures more market share due to its innovative solutions that solve a problem for a diverse group of people. The competitor accomplishes this feat because of its ability to leverage its people’s differences to produce goods and services that are relevant to its diverse market.

Beyond this loss, organizations that stifle individuality are adding more cost that result from a likely high turnover rate and poor employer brand. Lack of inclusion is extremely costly for an organization.

Finally, workplaces that do not honor individual differences create incredibly lonely work environments due to a lack of genuine empathy and understanding. These environments may render actual harm to the individuals who work there every day. When people feel lonely, when they don’t find meaning in their work, and when they feel they cannot learn and grow, their physiological and psychological well-being is negatively impacted, which may contribute to maladies, including cancer, addiction, diabetes, and heart disease.

Considering these factors, inclusion is not a “nice to have” within organizations; it is a must for creating a successful organization with employees who enjoy high, subjective well-being.

The Maturity Continuum for Diversity and Inclusion

The path toward inclusion, both inside and outside the workplace, starts with the individual.

All of us have evolved internal mechanisms that we use to simplify and compartmentalize information (e.g., the Ladder of Inference7), which have allowed us to make quick decisions even with the massive amount of information that comes our way constantly. These mechanisms work well when facing familiar situations and contexts, but more than ever we find ourselves immersed in new cultures, increasingly diverse teams, and a shift in technology that challenges the efficacy of these mechanisms. As the perspectives that drive our behavior become overly simplified or no longer serve a different context, we make decisions that no longer serve us well.

One issue is that the simple word “diversity” represents a very broad category. While we often think of gender, age, race, or ethnicity when we hear the term, there are many other forms of diversity that we need to manage effectively. We may face diversity of appearance or lifestyle; long-term forms of diversity, such as personality, attitudes, and internal values; and short-term shifts based on mood, feelings, and the current context, which are also forms of diversity. In the workplace, we encounter forms of diversity involving education and skills, role and seniority, and organizational power distance. Diversity comes in many forms, and as our environment changes around us, what is important also shifts, and how a particular behavior is perceived by others can shift as well.

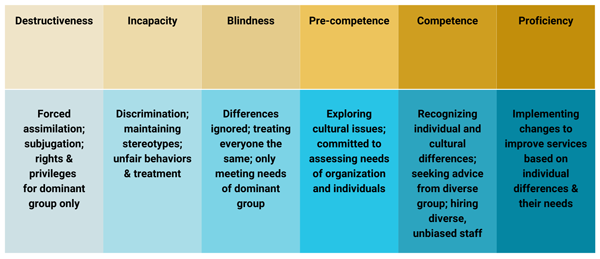

It is often assumed that we tend to see diversity and inclusion as Boolean elements — we are either a diverse team or we’re not, we’re inclusive or we’re not. In reality, we exhibit a continuum of maturity as we deal with these issues, ranging from destructiveness to proficiency.

The many examples of diversity continuums available online almost all focus on culture. Based on these, we have created a continuum of diversity competency (see Figure 1) that illustrates how our awareness, attitudes, and skills evolve as we develop competencies for intercultural interactions and learning.

Diversity Competency Research

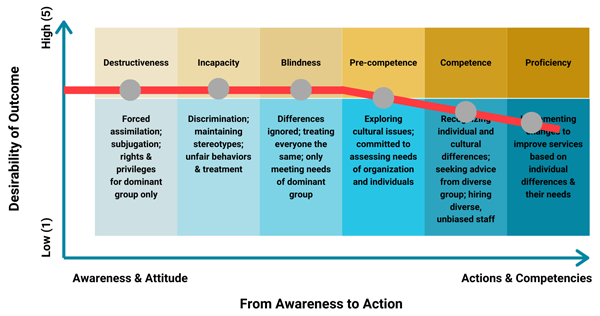

To understand where our society falls on this continuum of diversity competency, we assessed 150 professionals from different industries in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. Figure 2 summarizes the data findings from this research. On the y-axis, a high average desirability score means that the average response of participants in a given category presented the desired, positive, and constructive outcome. For example, high desirability in the category “Destructiveness” means that participants presented the desired and constructive behavior in this category and scored low on having a destructive attitude, such as a discriminatory attitude. Most participants scored very well and presented the desired outcome on the questions that measured level of awareness and attitude toward diversity. However, the average score of participants dropped significantly in the areas of taking actions and implementing changes.

There are a couple possible explanations for this pattern:

-

Social desirability bias.8 Individuals tend to overreport socially desirable characteristics or behaviors in themselves and underreport socially undesirable characteristics or behaviors. It may be a fair assumption that our participants chose responses that they believe are more socially desirable or acceptable rather than those that provide a true reflection of themselves. However, it is much easier to reflect on one’s tangible actions when being questioned on specific change behaviors rather than on beliefs; therefore, we observed a drop in the competence and proficiency score for behavior-related questions.

-

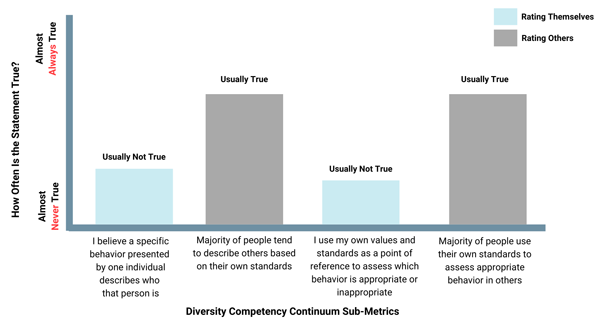

Illusory superiority bias.9 Individuals, when comparing themselves to others, overestimate their own desirable qualities and underestimate their undesirable qualities. Figure 3 shows our data findings that could support this assumption. When participants were asked to rate themselves on diversity competency metrics, they would report that it is usually not true that they themselves present the undesirable behaviors. However, they would report that it is usually true that others present the undesirable behaviors.

Another important finding from our research relates to the confusion around the definitions of diversity and inclusion and how to distinguish these two concepts. The majority of participants defined diversity in terms of ethnic background, individual differences, acceptance and welcoming of differences, equal rights, and “hearing different voices.” However, we observed similar themes when participants were asked to define inclusion. We may, therefore, conclude that there is a lack of real understanding of what diversity and inclusion are and what distinguishes one concept from the other. Our research findings may perhaps provide some insight into where to start to move the needle on diversity and inclusion. For change to occur, there must first be a real mutual understanding of the concepts involved as well as the ideal end point.

Working in Teams to Build Inclusion

In a team setting, the emphasis on building and maintaining an inclusive team culture should be just as strong and relentless as the emphasis on managing a current plan to completion — failure to emphasize either one will bring challenges to the team environment.

Inclusion in the workplace can largely be distilled to the degree to which everyone experiences psychological safety. Do all employees feel empowered to express their perspective, particularly if they feel they are being diminished in any way? If your people withhold or temper their opinions when the boss is in the room, you’re not there yet.

If your organization has a culture where employees “leave personal issues at the door” or individuals are not appreciated for being who they are in any sense, you’re not there yet, either.

Building inclusion in teams starts the very first moment someone joins a team and is continually being refined as long as the team is intact. Through appreciative conversations about past experience, exploration of what members hold as core to who they are, and taking the time to process different perspectives on an issue, the team works together to develop norms of behavior that will allow everyone to engage with a strong sense of self-worth.

Often there is pushback on this process, either generically (seeing inclusion as “that theoretical stuff”) or more specifically (“there’s a lot of work on this project; we don’t have time for this”). In reality, though, for organizations that do careful cost accounting, much of the time and money wasted on projects has its basis in some form of communicating ineffectively, withholding opinions, or diminishing the perspectives of others. Building and managing inclusion in teams is therefore an investment that can be among the strongest ROI measures for the organization.

Improved Organizational Approaches to Strengthen Inclusion

To take the steps necessary to move the diversity and inclusion needle within organizations, we must first understand that organizations are responsible for the well-being and growth of their members.

Through the lens of the economy and employment, we view businesses and companies as organizations that offer goods and services. However, we barely talk about the significant role that organizations play in fostering the growth and well-being of employees. If all the people the organization promotes are similar (i.e., not diverse) and no one exhibiting diversity has had the opportunity to grow and advance, the organization is certainly responsible to explain this dissonance.

Human development is largely shaped by the systems and environments with which we interact. The first of these systems is our family, followed soon after by our experience in the system of educational institutions. We then enter the workforce, where we spend 30+ valuable years and large portions of our days, often not reaching our full potential. Therefore, organizational leaders need to understand their important role and responsibilities in shaping the development and growth of their employees. In other words, another important product of the organization, besides goods and services, is also its most valuable asset: its people.

When we are evaluating how dedicated organizations are to the growth and development of their members, we need to consider several questions:

-

What resources does the organization invest in its people to ensure they are developing the essential skills for global interactions?

-

To what extent is the organization willing to understand its blind spots?

-

What responsibility does the organization accept for creating leaders that add value, not only to the organization, but to society?

-

How much does the organization invest in creating a safe environment where people can bring their whole selves to contribute to the company’s growth?

As leaders within organizations, it is essential to recognize that as soon as we hire someone into our workplace, we are responsible for that employee’s personal well-being and growth. We must create an environment where that individual feels included and where it is safe to make mistakes and to challenge the status quo.

Second, we must understand the power organizations have in building culture. We must be careful that our organizational norms and rationales are not defined solely by the company founders and/or national norms and rationales. We have the authority and responsibility to learn from each other and develop new ideas about how to have a distinctive, unique culture that helps our company and our people succeed. The cultures that organizations build affect not only the organization’s members, but also its customers, partners, communities, and other stakeholders.

A society consists of organizations. If each organization plays its part in creating diverse and inclusive environments, we can create a society that values differences and provides equal growth opportunities for all, regardless of age, sex, race, gender, socioeconomic status, mental health, or physical ability.

Third, we must recognize and understand the urgent need to develop our skills for interacting in a diverse environment. Due to the fast pace of globalization and expansion of technological communication, we are being presented with tools and environments that we often are not prepared to navigate. We do not have the skills required to use these new tools wisely, largely because change is happening at such a fast pace that we are not able to adapt organically. For this reason alone, diversity learning and training should be a mandatory, key component of every organization’s onboarding process.

Finally, we must understand the importance of keeping our diverse teams engaged by constantly evaluating and readjusting our reward systems, recruitment systems, and policies to accommodate and appreciate individual differences. Doing so will encourage greater employee engagement and higher performance in the workforce. One of the main reasons we spend significant resources on employee training, benefits, performance management, and rewards but do not achieve an acceptable ROI for these efforts is that we develop recruitment and reward systems based on our own norms and standards without considering individual differences in motives, values, talents, and norms.

References

1Rogers, Everett M. Diffusion of Innovations. 5th edition. Free Press, 2003.

2“CAN/CSA-Z1003-13/BNQ 9700-803/2013 – Psychological Health and Safety in the Workplace.” CSA Group, 2013.

3“About Daniel Pink.“ danpink.com, 2020.

4“About Brené Brown.” brenebrown.com, 2020.

5“Simon Sinek.” simonsinek.com, 2020.

6A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide). 6th edition. Project Management Institute (PMI), 2017.

7“The Ladder of Inference: How to Avoid Jumping to Conclusions.” MindTools, 2020.

8See Wikipedia’s “Social desirability bias.”

9See Wikipedia’s “Illusory superiority bias.”