Two years ago, my ophthalmologist sent me spiraling into an early midlife crisis. He casually mentioned that my eyeglass prescription would now be altered to correct my inability to read text at close range, a common experience for folks my age. The thing is, I didn't know until that very moment that I had a problem reading text close up. Just 20 minutes before this pronouncement, I had been blissfully reading magazines in the waiting room without issue, then suddenly the print didn't look so crisp. Indeed, almost instantly the same magazines were now out of focus.

I'm sure it was just a coincidence, but at the same time that my corrective lenses brought my computer screens, books, and magazines into focus, I was suddenly confronted with the reality that the IT project management office (PMO) that I have directed at the Massachusetts Medical Society (MMS) for the last 11 years had lost its value proposition. Our emphasis on the methodology for implementing critical business systems such as manuscript tracking, advertising, fulfillment, membership, and enterprise resource planning (ERP) was considered ineffective for managing Web product development. Suddenly the word "process" was banned in favor of lightweight, agile, innovation-style management in which experimentation, changing course, and redos were considered good. Under this mandate, the successful project managers concentrated less on the academic process of managing projects and more on establishing relationships, learning the business, and insisting on implementable results sooner and more often.

Over the last few years, when recruiting project managers, I've been challenged to describe what combination of skills is required to lead projects in diverse areas of the organization and how the project manager role differs from the more contemporary Web producer role or product manager role that now coexists within online product teams. The framework that I developed to measure project management performance was being challenged, and my PMI-based best practices approach was being described as "out of sync" with what project managers supporting online products were experiencing. To convey the significance of these challenges and the actions I took to correct course, I first need to explain how the project management discipline began and evolved at MMS.

THE EVOLUTION OF THE PROJECT OFFICE

Back in April 1992, I was hired into the editorial offices of The New England Journal of Medicine, the MMS's flagship journal, as their IT manager. At that time, the editor-in-chief provided a clear technical vision for me to follow, which was to network his office, implement desktop publishing, and rewrite the mainframe application for managing the manuscript pipeline. To get these projects done, I relied on several things:

- The vision and sponsorship of the editor-in-chief, who outlined clear goals and provided funding, influence, and decision making

- My ability to unite silos and create bridges with my counterparts and colleagues

- The knowledge provided by staff, consultants, and vendors

- My own organization skills and determination

We experienced success in all these endeavors, but I did not define myself as a project manager or attribute success to a defined project methodology. More likely, it was the small focused cross-functional team and the influence and leadership of the editor-in-chief that mattered the most.

The advent of a CIO in 1997 meant a consolidation of the IT satellites. I was offered a chance to work directly for the CIO at headquarters to define project standards ahead of large and looming critical business system projects. With my limited exposure to business planning and unaware of any specific IT strategy, I understood the primary drivers for these major undertakings to be:

- The continued shift away from a mainframe-based technology platform to a client-server platform built on Microsoft technologies

- A remediation response to the looming Y2K date bug

- An emphasis on vendor-supported off-the-shelf business applications

I also understood that as an individual contributor with no formal project management training, I faced a huge challenge in introducing standards and best practices. I started by making the same mistake as others have in the past -- immediately leaping to the conclusion that a Microsoft Project schedule was the lynchpin of successful project management. By jumping right into "doing" tasks, I skipped steps designed to clarify the business goals, success criteria, roles, responsibilities, assumptions, and constraints that elucidate purpose and scope, as well as help to motivate a team and properly manage stakeholder expectations. After talking to vendors, doing Web research, and completing a project management certificate program, I adopted these best practices and was able to more effectively manage my own projects and begin to define structure and process for IT projects in general. Having achieved success in my own endeavors, I was able to share this knowledge and build interest in the discipline. My Project Office of one grew by enlisting the support of our technology training coordinator and establishing regular education sessions and regular meetings for project managers to share their experiences.

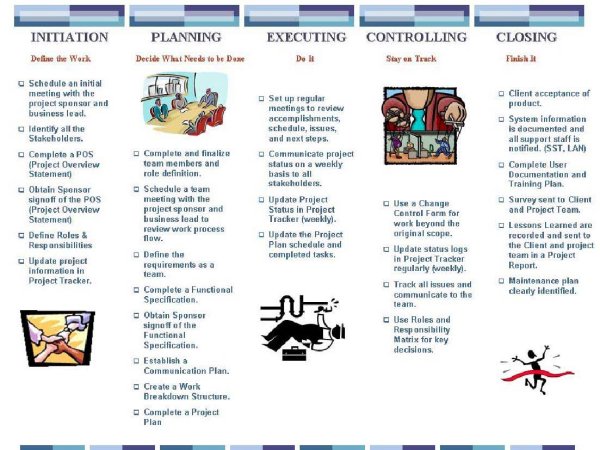

As a result, interest in project management grew across the enterprise and a shared language was forming. An example of some of our training material is shown in Figure 1. This project management process chart underscores our emphasis on teaching the process of project management and the key artifacts that should result from each stage.

Figure 1 -- Project management process chart.

By 2003, six years after the CIO was hired, our now two-member Project Office had established a project management discipline, a knowledge base, a user group, a portal, and a portfolio of successful endeavors. The Project Office established a more disciplined approach to IT resource planning and the instantiation of the client relationship role. At least 15 folks in the organization were approved to take a project management certificate course. We were down the road to a disciplined approach to managing large cross-functional efforts, very much into the process -- or the "how" -- of doing projects.

The Maturing of the Organization

The success of the methodology and its positive impact on large-scale projects, the growing project pipeline, and the increasing requests for project managers led to the decision to put three project manager positions in the IT Project Office and to add several project manager positions directly in business units. These positions were targeted to help drive projects for three distinct portfolios within the organization: online (Web) publishing, corporate business systems, and physician membership-driven initiatives.

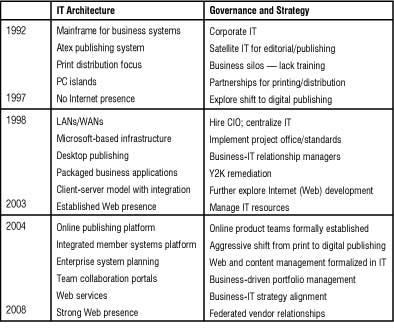

What wasn't obvious to me then but is very clear to me now was the fact that the business and IT were preparing for another major shift. Back in 1997, we needed to establish an internal base of systems and workflows to support the running of the core business. An emphasis on examining process made sense. In 2003, the focus changed from tactical implementations to transformational business planning, which meant identifying the platforms needed to support our publishing division's move to Web publishing and the MMS's emphasis on member self-service through portals and online communities. Table 1 gives you a good sense of how the business change occurred over time and how the alignment of business and IT strategy became more visible.

Table 1 -- IT Architecture and Governance

Two results of the changing business focus were an emphasis on creating online product teams in an organization geared for print production and a shift away from deciding how to do projects to determining which projects we should do and why we should do them. IT was pressured to provide strategic direction for these technology shifts, and project managers were frustrated by incomplete business cases at project startup, business silos, competing resources, and a lack of defined business processes for the online work. The dynamics of a back-office system enhancement project (process focus) differed sharply from those of a Web site enhancement project (iterate and innovate). In addition, the organization had less of an appetite for project metrics (although important to IT) in favor of business analytics that supported business development and ongoing releases of online product functionality.

Based on these drivers, several things happened that impacted the mission of the IT Project Office. First, the establishment of online product programs and a publishing portfolio team emphasized business-driven governance for project selection and prioritization. Second, the establishment of a publishing-oriented media technologies team in IT to manage the online product development (enhancement pipeline) meant a change in work intake and allocation. Third, and most important, a reorganization of IT decentralized the Project Office, morphing it into a program entity to support key technical portfolios in the business. Program director positions were established, and project managers were assigned into three IT program areas: publishing, corporate systems, and membership.

Even though I was slow to recognize the shift, one thing that has helped me assimilate this change in the IT Project Office -- from project execution and metrics to portfolio oversight and business relationship management -- is that it closely follows trends identified by leading sources of IT research. For instance, CXO Media's The State of the CIO `08 report found that although most CIOs are consumed by transformational duties (business process change) and alignment, "the position, to be viable long-term, needs to adopt more of a business strategist focus and activities."1 In essence, what I am experiencing is being reflected in the industry. The direction we have taken to concentrate less on process and more on business development is in line with industry expectations.

MANAGING PROJECT MANAGERS AND ORGANIZATION DYNAMICS

Although the IT Project Office has experienced significant changes in focus, there is still support for the project manager role. However, to make project managers more viable -- for them to be seen as more than just administrators -- I have had to deemphasize process and shift attention to business analysis (i.e., good clear requirements and quality of results) and relationship management.

In the past, when working one-on-one with project managers and identifying performance goals, I used to emphasize these PMBOK-like2 activities:

- Active integration management. The project manager is responsible for developing, monitoring, and communicating a project plan to determine how individual phases and issues might impact the overall schedule and goals of the project. At the time of executing, the project manager is the hub of coordination and communication for his project(s).

- Active scheduling. This activity ensures that project milestones are indicated and task timelines and dependencies are clear.

- Proactive progress tracking. The project manager spends time each week keeping track of all activities on a project, communicating with team members to ensure deliverables are on track and folks are prepared for meetings and next steps.

- Regular communication. Each week the project manager updates status in the enterprise project information database and sends regular status reports to the project team. She uses various methods of communication (meetings, e-mails, reports) as appropriate to inform teams and clients regarding the status of a project. Effective communication is the project manager's number-one priority and the task on which she spends the bulk of her time.

- Proactive issue tracking and resolution. The project manager gains a full understanding of the issues on his projects to determine the most effective means to resolve and/or appropriately escalate issues.

Now, with the input and help of newly hired project managers, we've documented a new set of criteria for effective project manager performance:

- Facilitation for action. The project manager must know how to drive a group or team toward the shaping of work, the decisions to be made, and the commitment required.

- Efficiency. A good project manager constantly checks for speed and efficiency. She helps the team focus and removes roadblocks.

- Integration. The project manager knows all the pieces that must knit together for a project to move forward and understands how the entire business process is impacted. He sees synergies with other projects and operations.

- Agent of change. The project manager understands how the project impacts the business and helps stakeholders make -- and adjust to -- needed changes.

- Consultation and analysis. The project manager is able to provide a credible starting point for the scoping of an effort and to understand the business process and requirements.

- Information dissemination. This activity involves not just basic status reporting but a true analysis of how the project is doing compared to its objectives. The project manager must provide substantive, cogent reporting.

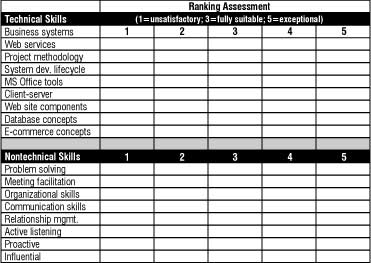

These new performance measures emphasize a role for the project manager that is more facilitative and consultative in nature. In recruiting technical project managers, I've been careful to look for a balance between their technical and process-driven capabilities and the necessary soft skills for creating relationships and influencing teams. The Project Management Professional (PMP) credential helps, but it is often less significant than experience and personality fit. Figure 2 is a snapshot of the interview grid I have used to rate key skills and ensure that I cover all aspects of a project manager's fit into our organization.

Figure 2 -- Interview grid for rating key project management skills.

Because I have such different aspects of our business to cover, I need to emphasize skills differently for each area. For instance, in our corporate area, the project manager should have experience working with cross-functional business teams to define workflow, configuration, interfaces, and testing for packaged enterprise business applications. In the publishing area, the project manager must understand how the content, creative design, and programming of a Web site is produced in conjunction with product development teams and with direct feedback from customers. Corporate systems projects take a linear approach to designing and verifying a business process, whereas publishing projects engage in a high level of collaboration, redo, and multiple iterations before a final product is implemented.

What I've realized personally -- and what I've been trying to emphasize to new project managers in my organization and in the certification courses I teach -- is that there is a need to split the focus between work roadmap execution and relationship management. When I talk about work roadmap execution, I'm talking about the project manager's ability to scope work; understand the big picture; concentrate on results, deliverables, milestones, goals, and measures; and progressively elaborate the work and process with her team throughout the project. When I talk about relationship management, I'm talking about the the project manager's ability to develop positive team dynamics, manage stakeholder expectations, manage reporting relationships, clearly define roles and responsibilities, communicate well, negotiate diplomatically, and, most importantly, collaborate in a politically savvy way to achieve results. I've seen both approaches achieve results, but I've seen the most success when the two are blended.

CONCLUDING THOUGHTS

My organization has multiple personalities. It is a publisher and a membership organization. It is both margin-driven and mission-driven. It is functionally organized but committee-driven. In no way do we resemble a projectized organization. Our revenue streams are based on subscriptions, dues, and advertising. Projects are not the means for accomplishing our day-to-day business. Business unit autonomy makes it difficult to enforce enterprise standards. Therefore, there is no appetite for investing large amounts of resources or infrastructure to provide detailed project scheduling, resource capacity planning, portfolio-level project dashboards, or sophisticated business requirements management. With that said, even in this climate, projects are the means for creating business change, and they do need to be visible within the IT portfolio. Therefore, some level of consistent execution and reporting is required. Lately, IT activity at MMS has largely consisted of shorter-cycle enhancement release work. This is supported by tracking tools that are easy to purchase and configure and that require less overhead to manage as compared to sophisticated project information systems.

In this business climate, IT has struggled to define its role within MMS. Eighty percent of our IT activity is focused on operations, yet we must participate in business development. Our staff must not only have strong technical skills, but it must also become more aware of how the business runs, what it cares about, where it is headed, and how technology is used to achieve its goals. Our newly defined program areas (i.e., our redefined IT Project Office) were created to help IT with this transition.

Buoyed by research and my recent experiences, I believe the focus that the PMO is now taking is the right one for our organization. Nevertheless, the transition has not been an easy one for me personally. As a very committed PMO director for 11 years, it is hard for me to let go of the mission to be a centralized project nerve center. As an IT professional for close to 20 years, it has been difficult for me to temper my natural inclination toward process and technology for their own sake versus deepening my understanding of our business and why it functions. And in pioneering processes to drive critical projects to completion, I've gotten a reputation for being bureaucratic and inflexible, something I must undo.

So now I strive to reinvent myself by providing the right balance between work results and relationship management, process, and substance. In traversing this midlife crisis, my PMO and I are doing fine, because our ideals have been tempered by practical sensibilities based on tangible experience (lessons learned, if you will). And that I can see with or without my glasses.

ENDNOTES

1 The State of the CIO `08 . CXO Media, Inc., 2007 (http://a1448.g.akamai.net/7/1448/25138/v0001/compworld.download.akamai.com/25137/cio/pdf/state_of_cio_08.pdf).

2 The "PMBOK" refers to the Project Management Institute's A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (www.pmi.org/Marketplace/Pages/ProductDetail.aspx?GMProduct=00100035801).

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Bonnie Cooper is a 20-year IT professional, currently Program Portfolio Director of the Massachusetts Medical Society's (MMS) Corporate IT Program Office. Early in her career, Ms. Cooper managed application and network migrations for Zayre Corp. and Dun & Bradstreet. In her tenure with MMS, her project portfolio includes The New England Journal of Medicine's manuscript tracking, desktop publishing, advertising management, and corporate enterprise resource planning systems. In her current role, Ms. Cooper is responsible for coordinating the efforts of project teams, managing the portfolio and strategic planning exercise for IT, and leading the project to redesign the MMS's membership systems platform. She is a member of the Project Management Institute and an instructor in two project management certification programs (Boston University Corporate Education Center and Northeastern University's Management, Leadership, and Technology Division). Ms. Cooper can be reached at BCooper@mms.org.

In this issue of Cutter IT Journal , we discuss the complex issues surrounding project management in the new global environment. Discover how one IT executive is overcoming her PMO's "midlife crisis" by shifting its focus from project execution and metrics to portfolio oversight and business relationship management. Learn how your projects can reduce their "Feature-Time-to-Benefit" through a combination of lean, agile, and Toyota Production System (TPS)-inspired techniques. And hear from one author who relates "a typical agile failure story" and argues that we need to go beyond agile project management to ensure that the value project teams deliver represents coherent and complete content. Be sure to tune in - the project you save may be your own!.