AMPLIFY VOL. 36, NO. 2

Matthew Walsh explores the results of in-depth research conducted to identify the inequities that women of color experience in the technology industry. He begins his piece by pointing out the “occupational segregation” that exists in the workplace with the underrepresentation of Black, Latino, and American Indian women in fast-growing sectors. To help mitigate this concern Walsh offers the Equation for Equality, a tool employers can use “to expand their talent pool in a low-risk way by identifying workers outside a given sector who use a similar skill set to the one required by an open position.”

Black, Latina, and American Indian women are underrepresented in most well-paying, fast-growing sectors, a phenomenon known as “occupational segregation.” Mitigating this problem requires career transitions across roles and sectors so that women of color can attain good jobs in areas where they are currently underrepresented.

Career transitions are difficult because individual workers assume most of the risk. For instance, a person must decide to reallocate time during the week to invest in education, search for a new job, and travel to interviews, and then make the decision to leave a familiar job for a less familiar one.

Of course, employers do assume some risk when hiring someone making a career transition. If the hire is a bad match, the employer absorbs the cost of hiring and onboarding that person. This makes hiring managers averse to engaging with candidates without previous experience in the sector and/or a college degree linked to the open position.

This employer reluctance to engage with career-changers means that many individuals decide not to invest in education or a job search; they assume they will not be considered for a position for which they do not have work experience or a degree. That cycle cements occupational segregation.

The cycle has another effect: it exacerbates the perception of labor shortages. The average number of open job postings per unemployed worker has increased from fewer than one to more than two over the last three years.1 That figure is increasing because the demand for new employees is rising faster than the supply of workers that employers are considering for open positions. But the more employers restrict the size of their talent pool (e.g., by requiring a candidate to meet a narrow résumé profile), the more difficult it is to fill open positions. Shortages are felt most acutely by employers that are reluctant to consider nontraditional job seekers.

The Equation for Equality, discussed in this article, tackles the issues of occupational segregation, labor-shortage acuteness, and the risks faced by both individuals and employers when engaging with career transitions.

The equation gives employers a way to expand their talent pool in a low-risk way by identifying workers outside a given sector that use a similar skill set to that required by an open position. Rather than viewing sector experience, academic pedigree, or employer history as the most relevant signals during hiring, the equation helps employers identify good employment matches based on skills.

By focusing on skills, the equation sets employers up to collaborate with skills-training organizations that can: (1) stand up to the type of training that employers need; and (2) connect employers to graduates of skills-training programs that teach the relevant skills, even if those graduates don’t have the traditional work experience or educational background the employer typically requires.

Centering the Issue of Occupational Segregation

Black, Latina, and American Indian women hold 14.6% of jobs nationwide but only 8.2% of jobs that make more than US $25 per hour on average.2 Among the 20 occupations with the greatest number of Black women, only three earn above $25 per hour on average. That figure drops to one for both Latina women and American Indian women.3 People of color are overrepresented in the lowest-paying jobs, making up the majority of workers in all 25 of the lowest-wage occupations.4

A lack of upward mobility across occupations and sectors perpetuates the occupational segregation that locks women of color out of well-paying, fast-growing jobs. For example, nearly a third (32%) of Black women in the US would need to change jobs for their occupation mix to look like the mix of occupations held by all workers in the economy.5

To the extent that intergenerational mobility in the labor force does exist, it can largely be attributed to college education. Earning a college degree can break intergenerational correlations between the incomes and occupations of children and their parents.6 A bachelor’s degree boosts earnings by $20,000 over an associate’s degree and $25,000 over a high school diploma.7 Interventions that improve access to college and support college completion among women of color will undoubtedly reduce the wage and wealth disparities experienced by this group. But a college degree should not be the only way to break out of occupational segregation.

Indeed, if a college degree is the only way to break out of occupational segregation, we risk leaving many women of color without a solution. Only 35% of adults in the US have a bachelor’s degree or higher. That figure drops to 27.7% of Black women, 21.6% of Latina women, and 18.1% of American Indian women.8 Prioritizing college as the primary lever for labor force mobility would mean overlooking the millions of women of color who are already in the workforce and would face significant barriers returning to college.

The greatest potential lever for upward mobility is the vitality of the labor force. The US economy generates millions of job openings every month,9 and policies and practices at the individual and firm level determine who fills those openings. Ultimately, employers should be the greatest accelerant of labor force mobility for women of color. Fortunately, employers have many tools, resources, and organizations that they can leverage to support equitable hiring; the Equation for Equality is one such tool.

Understanding the Equation for Equality

The Equation for Equality aids in an equitable hiring process. It generates four helpful outputs:

-

A top-of-the-funnel benchmark for candidate diversity. Hiring managers should aim to meet or exceed this benchmark before advancing to interviews or subsequent stages in the hiring process.

-

A list of skills-similar occupations to include within the talent pool for a given position. This list of occupations expands otherwise narrow requirements around work experience and education.

-

A list of skills that workers from the skills-similar occupations would carry into the new position. These are skills that employers can test for during the hiring process to ensure a strong employment match.

-

A list of skills commonly required by the new position that the worker from the skills-similar occupation would have to acquire. Employers can train for some of these skills during the onboarding process and work with external training organizations for the rest.

The Equation for Equality Is Built in 3 Steps

-

Create a skills-similarity score between occupations. The equation relies on a score for skills similarity between occupations.10,11 Skills similarity is the overlap in knowledge, skills, and abilities between two jobs. Although employment history is often a function of a given sector or career trajectory, many skills can be applied across multiple domains. For example, electronic medical records specialists have information system management, technical support, and data entry skills that are relevant in multiple sectors, not just healthcare.

-

Review the feasibility and desirability of transitions. Once a skills-similarity score has been created between all pairs of occupations, the equation takes into account the feasibility of the transition and the desirability of the transition. Feasibility refers to the two occupations having similar requirements between years of work experience and level of education. For example, an industrial engineering technologist and an industrial engineer may use many of the same skills, but the overwhelming expectation of a bachelor’s degree for the engineering role means that a career transition is not feasible for an industrial engineering technologist without going back to school. In this way, the equation reduces the risk for individuals interested in making career changes by focusing on transitions that are feasible. The transition must also be desirable, meaning that the next-step job has higher earning potential or other desirable benefits.

-

Bring in demographic characteristics. Finally, the equation compares the demographic characteristics of a given occupation with the demographic characteristics of all the occupations that share a high level of skills similarity and for which a transition would be feasible and desirable. The equation can then be used to reveal job changes that let people of color move from areas where they are overrepresented to those where they are underrepresented.

From these three steps, the equation generates the outputs outlined above. The top-of-the- funnel benchmark comes from looking at the race/ethnicity and gender characteristics of the full talent pool — not just people with work experience in the desired occupation but everyone with relevant skills experience. The equation also provides guidance on the skill sets that need to be taught or reinforced for individuals changing careers. Employers can work internally or with outside partners to stand up that training.

The Equation for Equality represents both a practical tool for employers and a paradigm shift in how employers approach hiring. Focusing on skills development can enable the marketplace to break the strictures of occupational segregation.

Applying Equation for Equality at the Sector Level

NPower, a skills-training and advocacy organization, and Lightcast, a labor market analytics firm, are working to apply the Equation for Equality to the tech sector. This sector is a good example of the expanded talent pool revealed by the Equation for Equality. Rapid digitalization across a broad range of non-tech jobs and the importance within the tech sector of skill sets related to business, operations, user experience, and customer support coincide to produce a much larger talent pool for traditional tech jobs than is typically considered.

Black, Latina, and American Indian women hold 5% of tech jobs.12 But when we apply the Equation for Equality to these occupations, we see that these women hold 10% of skills-similar jobs — those that use the knowledge, skills, and abilities commonly sought in the tech sector.

What’s more, this tech-eligible workforce is more than five times larger than the tech workforce. There are close to 5 million workers in tech occupations in the US but more than 25 million workers in jobs that share a high degree of skills content with jobs in the tech sector.

If employers tapped into this skills-similar, tech-eligible workforce, there would be nearly 250,000 more women of color in tech jobs today, double the number currently in tech.

Applying Equation for Equality at the Company Level

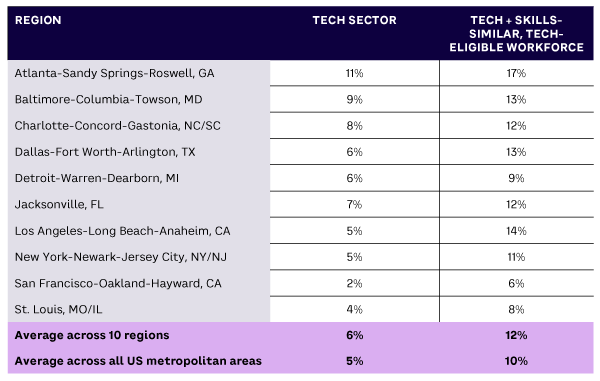

The Equation for Equality can also be used at the company level. NPower and Lightcast applied the equation across tech jobs in 10 large US metropolitan regions. With this data, employers can see the current demographic characteristics of the tech sector in their market as well as the demographic characteristics of the skills-similar, tech-eligible workforce that they could access. Putting these two candidate pools together reveals the demographic characteristics of the full tech-talent pool.

Firms can use these figures to set goals and benchmarks for the diversity of their own tech workforce. During the hiring process, companies can set top-of-the-funnel and bottom-of-the-funnel goals and benchmarks. The top of the funnel refers to the candidate pool at the first stage of the hiring process. The bottom of the funnel refers to the individuals who are ultimately selected. If companies benchmark the top of the funnel against the full talent pool and the bottom of the funnel against the current demographics in the tech workforce, they can be sure their hiring will promote equity within the sector over the long term. Table 1 shows how this looks in the 10 metropolitan regions studied by NPower and Lightcast.

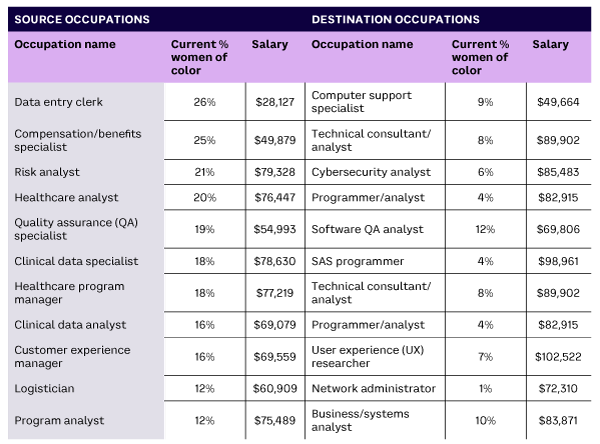

Companies can also refer to job-level data on the demographic characteristics of tech occupations and skills-similar, tech-eligible occupations. Table 2 shows a handful of examples. With job-level data, tech executives, HR professionals, and hiring managers can be intentional about recruitment and outreach to workers in skills-similar, tech-eligible jobs where women of color are better represented.

Finally, the equation can be applied at a company level to develop internal ladders for advancement. It can be difficult for C-suite executives to understand the internal pathways that exist within their workforce, but they often know which departments and teams are facing staffing challenges. By identifying the occupations facing staffing challenges, executives and HR leaders can use the equation to identify skills-similar feeder roles that can source talent for those occupations.

Many companies, especially large ones, find that they already employ workers in those feeder occupations. They can then devote resources in a targeted way to upskill workers in feeder roles so they can transition into those in-demand roles. This process develops internal career ladders that benefit the incumbent workforce, supports retention, and meets the organizational needs of the company.

Applying Equation for Equality at the Ecosystem Level

Employers will get the most out of the Equation for Equality when they tap into the broader workforce ecosystem to support skills development, recruit and retain diverse talent, and advocate for policies and practices that support diverse talent.

Workforce development organizations and advocacy organizations have deep experience working with groups that are underrepresented in well-paying, fast-growing career areas. Career service providers often serve underemployed individuals. Public funding and philanthropic giving are often connected to working with marginalized groups. Advocacy organizations and other nonprofits can help employers navigate access to complementary workforce assistance, such as housing and transit assistance. Employers can be key partners within this ecosystem.

When employers and outside partners use the Equation for Equality, they are able to speak the same language about talent development. Training programs that emphasize skills similarity between occupations will have an easier time attracting students because those students appreciate that with their existing skill sets, they are already on track to make a career change. Training programs that acknowledge those skill overlaps can also be more efficient, since they do not need to rehash the skills that students already possess. Employers are able to work directly with training providers, providing work-based learning, making commitments to hire from training programs, and replacing degree requirements with skills assessments.

For example, NPower assists with wraparound services such as transportation, career coaching, and access to professional networks and works directly with employers to develop relevant tech skills curricula. NPower and its employer partners roll out expedited interview tracks for program graduates and job-placement programs like apprenticeships.

NPower has also put together an employer coalition: Command Shift. The coalition focuses on attracting women of color to tech careers, increasing the number of companies that hire and retain women of color, and achieving pay equity for women of color in tech. The coalition has a number of working groups where employer partners can collaborate, share best practices, and keep one another accountable.

The coalition model can be applied to other sectors and can be constructed locally within a laborshed. Linking employers and connecting them to the broader workforce ecosystem can increase the impact of applying the Equation for Equality to the labor force.

Conclusion

Occupational segregation has perpetuated the underrepresentation of Black, Latina, and American Indian women in well-paying, fast-growing sectors. The Equation for Equality mitigates this problem by helping employers expand their talent pool for a given role. That expanded pool includes workers with many of the right skill sets but whose work histories are outside the sector or outside a narrowly defined occupation. Tapping into this expanded talent pool creates the potential for career changes that disrupt occupational segregation.

By moving employers to a skills-based paradigm, the Equation for Equality sets them up to address acute supply shortages, develop internal career ladders, and work in a more targeted way with skills-training organizations. The Equation for Equality both expands the talent pool and lowers the risk of bad employment matches by taking advantage of skill overlaps and bridging skill gaps.

The Equation for Equality complements other strategies for equitable hiring, retention, and advancement of women of color. The equation provides demographic benchmarks and targets the top and bottom of the hiring funnel, as well as internal promotions. The equation also encourages hiring discussions based on skills, which can be acquired at much lower cost to workers than earning a degree and reduces the need for career-changers to take a pay cut to enter an unfamiliar but faster-growing sector.

By prioritizing skill sets over sector experience, academic pedigree, or employer history, employers can expand their talent pool, mitigate the risks associated with hiring individuals making career transitions, and support labor force mobility for women of color.

References

1 Author’s analysis of Lightcast data on aggregate US job postings and employment.

2 “US Census Data for Social, Economic, and Health Research.” IPUMS USA, accessed February 2023.

3 IPUMS USA (see 2).

4 Langston, Abbie, Justin Scoggins, and Matthew Walsh. “Race and the Work of the Future: Advancing Work Equity in the United States.” PolicyLink/USC Equity Research Institute, 2020.

5 Alonso-Villar, Olga, and Coral del Río. “The Occupational Segregation of African American Women: Its Evolution from 1940 to 2010.” Feminist Economics, Vol. 23, No. 1, March 2016.

6 Chetty, Raj, et al. “Mobility Report Cards: The Role of Colleges in Intergenerational Mobility.” National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), July 2017.

7 “B20004: Median Earnings in the Past 12 Months (in 2021 Inflation-Adjusted Dollars) by Sex by Educational Attainment for the Population 25 Years and Over.” US Census Bureau, accessed February 2023.

8 “S1501: Educational Attainment.” US Census Bureau, accessed February 2023.

9 “Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (2012-2022).” US Bureau of Labor Statistics, accessed February 2023.

10 Walsh, Matthew, and Joel Simon. “The Equation for Equality: Women of Color in Tech.” Command Shift/Emsi Burning Glass/NPower, accessed February 2023.

11 “Towards a Reskilling Revolution: A Future of Jobs for All.” World Economic Forum, January 2018.

12 Walsh and Simon (see 10).